By Suzanne CostnerI headed to Houston in November 2018 to attend the NCTE Annual Convention and moderate a panel presentation for a group of children’s nonfiction writers. I was also looking forward to the Children’s Book Award Luncheon, never realizing that it would change my life. As the presentation of the year’s winners was winding down, an announcement was made encouraging attendees to apply for a place on one of the award committees. My sister nudged me and whispered, “You could do that.” Two months later, I was beginning my term on the Orbis Pictus committee and immersing myself in children’s nonfiction. From January 2019 through December 2021, we read over 1,300 books on topics ranging from amoebas to world history. As we reviewed, debated, and voted, my favorite topics involved astronomy, aviation, and aerospace, although I enjoyed all of them. The titles that combine those topics with a picture book biography make wonderful entry points into the study of science and history. Even though my time with the Orbis Pictus has ended, I am still searching out those sorts of books to add to my school library collection. I would like to share two of those titles with you and suggest related areas your students might enjoy investigating.

To learn more about her amazing career, try the following:

Students may find helpful information in the following:

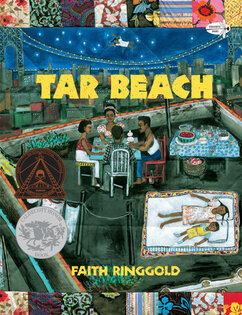

When I was a child visiting my school library, all the biographies were about famous presidents and other men. We still have a long way to go to balance the representation of women and other marginalized groups, but knowing there are authors and illustrators bringing these stories to life for today’s students is encouraging. Reading these stories of dreams achieved and challenges overcome may inspire young readers to pursue their own passions in life, or even introduce a topic to spark that passion. I hope everyone finds some nonfiction to engage their hearts and minds. Suzanne Costner, School Library Media Specialist at Fairview Elementary School (Maryville, TN) member of NCTE, CLA, ALA, AASL, ILA, NAEYC, NSTA, ISTE, CAP, AFA, AIAA By Mary Ann Cappiello, Jennifer M. Graff and Melissa Quimby on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse  Over the last two years, we’ve enjoyed sharing excerpts from The Biography Clearinghouse website. We hope that our interviews with book creators and our teaching ideas focused on using biographies for a variety of classroom purposes has been helpful to the CLA membership and beyond. This month, we’re very excited to share something different - a voice directly from the classroom. Melissa Quimby, a 4th grade teacher in Massachusetts, has written the inaugural entry in our new feature “Stories from the Classroom.” Melissa is the genius behind #MeetSomeoneNewMonday, a weekly initiative that has spread from her classroom to her grade level team to an entirely different school in just three years. This initiative launched when Melissa decided to share her passion for picturebook biographies with her students through interactive read-alouds. They were hooked! As Melissa writes, “Over time, I molded this project in intentional ways, and it evolved into an adventure that focused on identity, centered marginalized and minoritized communities, and cultivated thoughtful, strategic middle grade readers.” What started as a way to share nonfiction picturebooks as an engaging and compelling art form developed into a more nuanced exploration of global changemakers–past and present. With their weekly reading of picturebook biographies, students grow as readers and thinkers and deepen their individual and collective sense of agency. In the following excerpts, Melissa describes how she reveals each week’s notable changemaker to her students and shares some of her picturebook biography selections. Monday Read-Aloud Routines  Reveal Slide Example Reveal Slide Example On Monday mornings, we gather together as a reading community. In an effort to build excitement, our reveal slide is projected on the board as students arrive. Some weeks, copies of the backmatter wait on the rug, inviting students to preview the figure of the week. This could be the author’s note, a timeline, or a collection of real-life photographs. Once all readers are settled, we watch a video to learn a little bit about the person in the spotlight. Some weeks, interactive read aloud time happens on Monday morning immediately following the reveal. On some Mondays, it works best for us to huddle up in the afternoon. Occasionally, we steal pockets of time throughout our busy schedule to enjoy the biography of the week in smaller doses. When we read the text is not as important as how we read the text. The heart of this work truly lies in how we generate emotional investment within our students and how we help our students’ reactions and ideas blossom into new thinking about the world and ways that they can take action in their own lives for themselves and others. Sometimes, we simply read the biography to love it. In those moments, readers are silent with their eyes glued to the book, scanning the illustrations, wide-eyed when something surprising happens. Perhaps they whisper something to their neighbor, let out an audible gasp or share a comment aloud. Sometimes, we read to grow ideas. In these moments, readers are tracking trouble, considering how the figure responds to obstacles. They are ready to turn to their partner and reach for a precise trait word or theme and supporting evidence. To read more about #MeetSomeoneNewMonday, including Melissa planning process with her grade level team and student responses, visit Stories from the Classroom on The Biography Clearinghouse website You can also reach out to Melissa through her website (QUIMBYnotRamona) or Twitter (@QUIMBYnotRamona) to discuss how to implement #MeetSomeoneNew initiative in your classroom or school. Inspired by Melissa’s picturebook biography initiative or done something similar? Share your ideas and stories with us via email: thebiographyclearinghouse@gmail.com. Or, chime in on Twitter (@teachwithbios), Facebook, or Instagram with your own #teachwithbios ideas and picturebook biography recommendations. Melissa Quimby teaches fourth grade in Massachusetts. She is passionate about helping young writers improve their craft, and her to-be-read list is always stacked with middle grade fiction. Melissa shares her love of children’s literature on Teachers Books Readers and shares about her literacy instruction with the Choice Literacy community. You can connect with her at her website, QUIMBYnotRamona, or follow her on Twitter @QUIMBYnotRamona. Mary Ann Cappiello teaches courses in children’s literature and literacy methods at Lesley University, blogs about teaching with children’s literature at The Classroom Bookshelf. She is a former chair of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8. Jennifer M. Graff is an Associate Professor in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia where her scholarship focuses on diverse children’s literature and early childhood literacy practices. She is a former committee member of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8, and has served in multiple leadership roles throughout her 16+ year CLA membership. By Jessica WhitelawLast week I was able to visit the long-awaited Faith Ringgold exhibit, American People, at the New Museum in New York. Many know Ringgold from her book Tar Beach, but this retrospective - her first - features Ringgold as artist/organizer/educator and showcases paintings, murals, political posters, sculptures, and story quilts that span the Harlem Renaissance, the Black Arts Movement, critical feminism, and reach into the landscape of contemporary Black artists working today. After years of a relationship with the book version of Tar Beach, it was moving to stand in front of the original story quilt that the book is based on, this intimate everyday object upon which she wrote, painted, and stitched, to push the boundaries of white western art traditions and explore themes of gender, race, class, history, and social transformation.

Below is a protocol adapted from the steps of art criticism that can be used to support students in developing picturebook practices that engage critical literacy and inquiry. It can be used with Tar Beach, whose content is both accessible and complex enough to use with both younger and older readers. But it offers a flexible participation structure that teachers can use with any picturebook that has rich visual/verbal content. Like most protocols, it works best as a flexible tool not a prescriptive device. Picturebook Read Aloud Protocol Adapted from the steps of art criticism, this protocol provides a framework for sharing picturebooks that aims to cultivate a critical practice. It guides the reader through a process of looking closely to notice what they might otherwise overlook and to use what they know about words and pictures to analyze and make sense of what they see. The stages offer a helpful way to support students of any age through a process and unfolding of critical engagement that relies upon attention to specific details in the work to guide thoughtful engagement and response. The protocol is intended as a facilitation guide for teachers. Wording should be adjusted for the audience/age of the reader. LOOK CLOSELY Take inventory. Examine the cover of the book, the dust jacket and the endpapers. Look closely at the typography, the pictures, the words. Describe what you see and notice in detailed, descriptive language. ANALYZE Use what you know about picturebooks and design to analyze the words and the pictures. Look at the colors, the lines, shapes, textures. Try to determine the media the artist used to make the pictures. Examine the style of the language the writer used. Look for patterns, repetition, rhyme. Draw attention to the picturebook as a unique form of the book that relies on the synergy of the words and the pictures by asking how the words and pictures work together: What do the words tell you that the pictures do not? What do the pictures tell you that the words do not? What happens in between the openings? QUESTION Use questions together to probe and deepen. Stop and ask questions about pages that are visually and/or verbally rich or complex. What sense do you make of this page? How do you know that? Why do you think the author or illustrator chose to do it the way they did? What questions does the page raise for you, make you wonder about? CRITIQUE What do you think the author/illustrator is trying to do or say or show in this book? Who do we see in this book? Who is the audience for this book? Who do you think should read it? Whose voice/voices do we hear? Who do we not hear from? What ideas do you have about the topic/topics in the book? What do you think the storyteller in this book believes or thinks or wants us to know? What questions do you have about what the storyteller is saying and showing? What genre/category does the book belong to? What other work has this author and/or illustrator created and how is it similar to or different from this book? RESPOND After having looked closely at the book, what does this text mean to you? What does the story make you wonder about? How could this story mean different things? To you? To different readers? Additional Teaching Resources for Tar Beach Watch Faith Ringgold read Tar Beach Create a paper story quilt Listen to Faith Ringgold’s favorite songs Explore a Faith Ringgold Text Set:

For Older Readers: Watch the Ted Talk by Kimberlé Crenshaw on intersectionality Examine how Tar Beach explores identity and power at several intersections. Examine other artworks of Faith Ringgold such as her For the Women’s House mural at the Brooklyn Museum or her America series of paintings on the artist’s website Read Ringgold’s feminist artist’s statement from her memoir, We Flew Over the Bridge. Look for themes that connect across and examine how the different art forms allow the themes to be explored differently. Read other excerpts from We Flew Over the Bridge: The Memoirs of Faith Ringgold, and examine how ideas from her life take shape in Tar Beach. Consider the different forms of visual and verbal storytelling that she employs in her work and how ideas are conveyed through different modalities in each. Jessica Whitelaw is faculty member at the University of Pennsylvania in the Graduate School of Education and a member of CLA. By Kathryn Will and River Lusky As we emerge from a long winter with the lengthening of days to warm the earth, I am drawn to books that get us thinking about nature–the plant and animal life in the world. As the NCBLA committee will tell you, I love books about nature, and this year many of the books we reviewed for the 2022 Notable Children’s Books in the Language Arts award list were about the natural world. For this text set we chose three books that leverage nonfiction, poetry, and a picture book to develop content knowledge, build vocabulary, and encourage divergent thinking about the natural world. They invite readers to be curious about nature in both big and small ways. Teachers can easily deepen and extend the texts through a variety of activities, and we have created a few to get you started. Wonder Walkers

If you are interested in learning more about how Micah Archer creates her collages check out the two videos below. The first provides a a brief glimpse of her printmaking, and the second offers a much more extensive look into how she creates the collage materials and assembles them for the book.

What's inside a flower and other questions about science and nature

Author Read Aloud. Brightly Storytime is is a co-production of Penguin Random House. The dirt book: Poems about animals that live beneath our feet

Announcing the 2022 NCBLA list

These are just three of the 774 books the seven members of the Notable Children’s Books in Language Arts book award committee read and reviewed for consideration of selection for the 30-book list created annually. The careful analysis and rich discussions over monthly (and sometimes weekly) Zoom sessions allowed us to create a thoughtful list that meets the charge of the committee.

The charge of the seven-member national committee is to select 30 books that best exemplify the criteria established for the Notables Award. Books considered for this annual list are works of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry written for children, grades K-8. The books selected for the list must:

2022 NCBLA Committee members

Kathryn Will, Chair (University of Maine Farmington) @KWsLitCrew Vera Ahihya (Brooklyn Arbor Elementary School) @thetututeacher Patrick Andrus (Eden Prairie School District, Minnesota) @patrickontwit Dorian Harrison (Ohio State University at Newark) Laretta Henderson (Eastern Illinois University) @EIU_PKthru12GEd Janine Schall (The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley) Fran Wilson (Madeira Elementary School, Ohio) @mrswilsons2nd *All NCBLA Committee members are members of CLA Kathryn Will is Assistant Professor Literacy at the University of Maine Farmington. She served as Chair of the 2022 Notable Children’s Books in Language Arts committee. River Lusky is an undergraduate student at the University of Maine Farmington. By Ted Kesler I have just completed my position as chairperson of the NCTE Poetry and Verse Novels for Children Committee. Our list of notable poetry and verse novels that were published in 2021 as well as other information about the award can be found on the NCTE Award for Excellence in Poetry for Children page. In this blog post, I discuss three notable poetry books from this list that promote advocacy and provide lesson plan ideas to do with children. Photo Ark ABCPhoto Ark ABC: An Animal Alphabet in Poetry and Pictures, poetry by Debbie Levy and photos by Joel Sartore (National Geographic Kids, 2021). The diverse and playful poetry forms in Photo Ark ABC oscillate with vibrant pictures to create fascination with each animal that is represented. Here is one example:

The book is part of the Photo Ark Project, that aims to “document every species living in the world’s zoos and wildlife sanctuaries, inspire action through education, and help save wildlife by supporting on-the-ground conservation efforts” [Back Book Cover]. Therefore, the book provides wonderful online resources to use with children, which expand opportunities for classroom explorations. Here are some ideas:

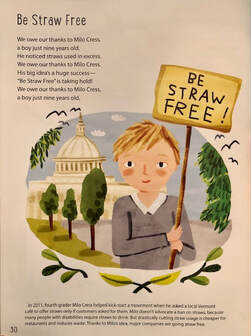

The Last Straw The Last Straw: Kids vs. Plastics, poetry by Susan Hood, illust. by Christiane Engel (HarperCollins, 2021).

My Thoughts are Clouds

My Thoughts Are Clouds: Poems for Mindfulness, poetry by Georgia Heard, illust. by Isabel Roxas (Roaring Brook Press, 2021).

Ted Kesler, Ed.D. is an Associate Professor at Queens College, CUNY and has been a CLA Member since 2010. He served as chairperson of the NCTE Poetry and Verse Novels for Children Committee from 2019 to 2021. www.tedsclassroom.com | @tedsclassroom | www.facebook.com/tedsclassroom) by Oksana Lushchevska

It takes a village to heal warriors – and it takes a warrior to teach the village how” state Raymond Monsour Scurfield and Katherine Theresa Platoni in their scholarly text Healing War Trauma: A Handbook of Creative Approaches.

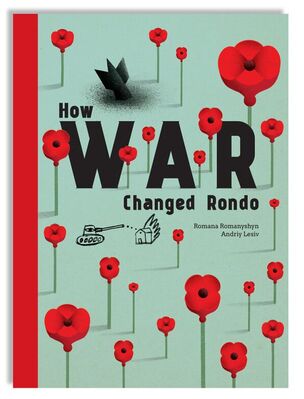

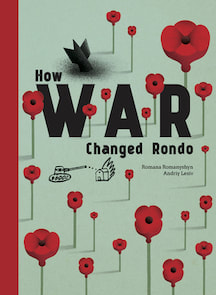

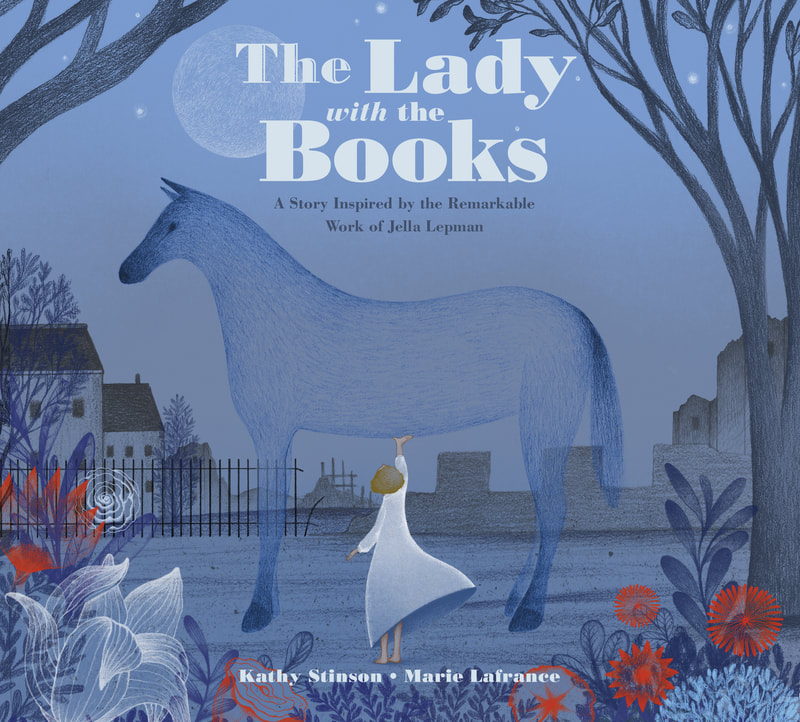

Following the horrific news from Ukraine, an independent, rapidly developing country located in eastern Europe, US educators and literature advocates seek tools to facilitate starting conversations about the devastating effects of war on humanity and the support every individual can offer, regardless of where they are. Children’s books can serve as a great tool to start deliberate, responsible conversations through classroom dialogue. Jella Lepman (1891-1970), a German journalist, author, and translator who founded the International Youth Library in Munich right after WWII, believed that children’s books are couriers of peace. She was certain that if children read books from other countries, they would realize that they share common human values and strive to preserve them. I believe that we, as global-minded educators and literature advocates, should, to use Scurfield and Platoni’s words, become warriors of peace; peacemakers who prepare our children to grow into wise, understanding, and sympathetic global citizens who have the will and the capacity to heal the world. Being originally from Ukraine and witnessing this horrific war unfolding in my country, where all my family and friends live, I feel the cruciality of this duty urgently and viscerally. Thus, I want to bring to your attention the picturebook How War Changed Rondo, which is a Ukrainian export. The book has been recognized as a Kirkus Best Book of 2021 and as a USBBY Outstanding International Book of 2022. Interestingly, this book was created by the Ukrainian book creators Romana Romanyshyn and Andriy Lesiv in 2014. The book won the 2015 Bologna Ragazzi Award, which is one of the most prestigious European Awards in children’s literature. I translated this book as soon as it was written. It was an imperative for me to bring it to the attention of English-speaking readers as it highlights a vital turning point in Ukraine's independent history: Russia’s annexation of Crimea and occupation of the eastern part of Ukraine in 2014 (Ukraine has been an independent country since the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991). I also felt responsibility to share with global young readers that we, as human beings, all want peace and democracy; we want to create and to thrive. In the picturebook, through the fictionalized characters, Danko (a light bulb), Fabian (a pink balloon dog), and Zirka (an origami bird), Romanyshyn and Lesiv depict the horrors of invasion of one’s own country, the impact of war, and the destruction in brings to everyone.

When I translated the text, I brought it to my classroom. It was 2015 and I taught a Children’s Literature course at the University of Georgia. When my students, who were future educators, read the text of How War Changed Rondo (the book was not yet published in the US), their empathy was sharp and deep. What’s important to know – I read the text without showing them the illustrations, so they could imagine the characters by themselves. After the reading, I invited them to write down their responses or/and to draw them. In particular, I invited them to imagine who the characters of the book are and what their injuries might look like. This was a very fruitful experience that further connected my students emotionally with the text and grounded their empathy. Finally, I showed them Andriy Lesiv’s original illustrations and they were touched by the perspective they created. You can use a similar approach when reading this picturebook in your classroom, or you can do it your own way. The possibilities are endless. You might also like to pair it with a short professional animated video of The War That Changed Rondo recently done by Chervony Sobaka (Red Dog Studio). This will be a good set to bring an intelligent perspective on such an important topic.

Donating to Help

If you are looking for donation options to support the people of Ukraine, here are some outlets for your consideration.

References

Lepman, J. (2002). A bridge of children’s books: the inspiring autobiography of a remarkable woman. Dublin, Ireland: The O’Brien Press, Ltd. Romanyshyn, R., Lesiv A., How War Changed Rondo. New York: Enchanted Lion Books. Scurfield, R. M., Platoni, K. Th. (2012). Healing War Trauma: A Handbook of Creative Approaches. New York: Routledge.

Oksana Lushchevska, Ph.D. is an independent children's literature scholar and a Ukrainian children's book author and translator. She is a publishing industry and government consultant in Ukraine and founder of Story+I Writing Group. She was a recipient of the 2015 CLA Research Award.

Website: http://www.lushchevska.com By Jennifer M. Graff, Jenn Sanders, and Courtney Shimek on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse

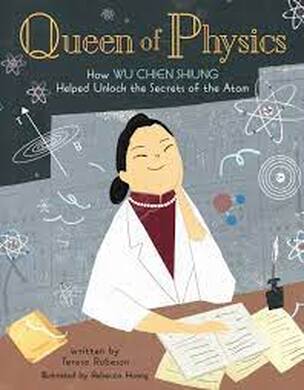

A Sampling of Wu Chien Shiung’s Accomplishments and Accolades |

| The first woman to

She also received

The Biography Clearinghouse’s latest entry includes interdisciplinary teaching ideas and resources that

This entry also features interviews with Robeson and Huang about their inspirations for this picturebook biography, connections to Wu Chien Shiung, and details about their research and composing processes, among other interesting topics. Below are three instructional ideas from this entry. |

Mentoring Via Peer Conferencing

Teach the mentor/tutor to pay attention to the writer’s ideas before worrying about spelling conventions.

“Respect the writer and the writer’s paper.”

Make the writer feel comfortable, be an active listener, and don’t write on the person’s paper.

“Involve the writer by asking questions.”

Teach mentors/tutors to ask open ended questions that get the writer talking about their ideas, their writing purpose, or their process.

“Teach the writer.”

Mentors/tutors share writing strategies that can be applied to the current piece but also across other pieces, rather than just trying to fix or revise the one piece they are discussing.

“Encourage the writer.”

Mentors/tutors provide encouragement by noting something specific that the writer did really well and offering one or two suggestions for revision (p.127).

Teachers can also invite students to consider the role of mentorship in their own lives. Students can identify individuals who have served as mentors to them and explore mentorship patterns and practices that are helpful and empowering to them as learners.

Advocacy and Activism

- Yuri Kochiyama was a political activist from California who fought with Malcom X to work for racial justice, civil and human rights, and anti-war movements. She went on to work in the redress and reparations movements for Japanese Americans and continued to fight for political prisoners until she passed away in 2014.

- Pranjal Jain is an Indian-American activist who has been organizing since she was 12 years old. As a current undergraduate at Cornell University, she is the founder of Global Girlhood, a women-led organization that inspires intercultural and intergenerational dialogue in online and offline spaces.

- Stephanie Hu is a Chinese American who founded Dear Asian Youth while she was a high school student as a support website for marginalized young people as a result of the rise in anti-Asian racism and violence during the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Anna May Wong was the first Chinese American movie star to appear in U.S. box offices. Although she was often relegated to smaller roles that perpetuated Asian stereotypes, her career spanned silent films, talkies, theater, and television, and she helped blaze the trail for Asian American performers after her. See Paula Yoo and Lin Yang’s (2009) picturebook biography, Shining Star: The Anna May Wong Story, published by Lee & Low Books.

Printmaking a Character for Fiction Writing

By using basic supplies such as styrofoam plates and markers for printmaking, students can create a character to print and use in their own creative story. Watch this short video of a teacher demonstrating the styrofoam printmaking process.

If you have 1-2 hours…. |

If you have 1-2 days… |

If you have 1-2 weeks… |

Each student can design a main character for a story they write, and then draw and marker-print the character on paper. In this activity, students will experience a process of printmaking that helps them understand the steps and all the work that goes into making printed images. |

After students create their printed character (see the If you have 1 to 2 hours . . . column), students can draft the story in which their character experiences a problem, challenge, or adventure. Based on their story, they can add a background setting in their picture to place their character in the context of their story. Students will simply draw the background setting and objects around their character on their printed picture. |

Students can print their character four to six times, on separate pieces of paper, to create a storyboard with multiple scenes. Save one of these prints to make a title page for the story. For this activity, we recommend students leave the background of the styrofoam plate empty so they can draw in different backgrounds as the story progresses. Then, they can divide their corresponding written story into sections (three, four, or five, depending on the number of prints they made). For each story section, they can draw in a related background setting, additional characters, or objects to help complete the scene. In the end, they will have a multimedia print that has their character marker-printed and the background drawn in with pen, marker, or other tools. |

Reference

Jennifer Sanders is a Professor of Literacy Education at Oklahoma State University, specializing in representations of diversity in children’s and young adult literature and writing pedagogy. She is co-founder and co-chair of The Whippoorwill Book Award for Rural YA Literature and long-time member of CLA.

Courtney Shimek is an Assistant Professor in the department of Curriculum & Instruction/Literacy Studies at West Virginia University. She has been a CLA member since 2015.

By Bettie Parsons Barger and Jennifer M. Graff

See the USBBY website for additional content and presentation considerations. |

As we look at the past three years of OIB lists, we recognize how our current realities are reflected in the committees’ selections. Julie Flett’s (2021) We All Play/ Kimêtawânaw illustrates humans’ innate connection to nature and the joyous experiences of playing outdoors, as the current pandemic has encouraged. The Elevator (Frankel, 2020) speaks to the power of humorous storytelling to unite strangers who unexpectedly find themselves in close quarters. The current Ukrainian-Russian tensions mirror the conflict in How War Changed Rondo (2021). Silvia Vecchini’s (2019) graphic novel, The Red Zone: An Earthquake Story, and Heather Smith’s (2019) picturebook, The Phone Booth in Mr. Hirota’s Garden, are stirring testimonies about ongoing global natural disasters, such as the recent volcano eruption and subsequent earthquake and tsunami that have devastated the Pacific nation of Tonga.

Partnering the beliefs that books including hostile and traumatic events “can provoke reflection and inspire dialogue that sensitizes readers . . .” (Raabe, 2016, p.58) and that “stories are important bridging stones; they can bring people closer together, connect them, and help overcome alienation” (Raabe & von Merveldt, 2018, p.64), we created a sampling of five text sets that can be readily used in K-12 classrooms.

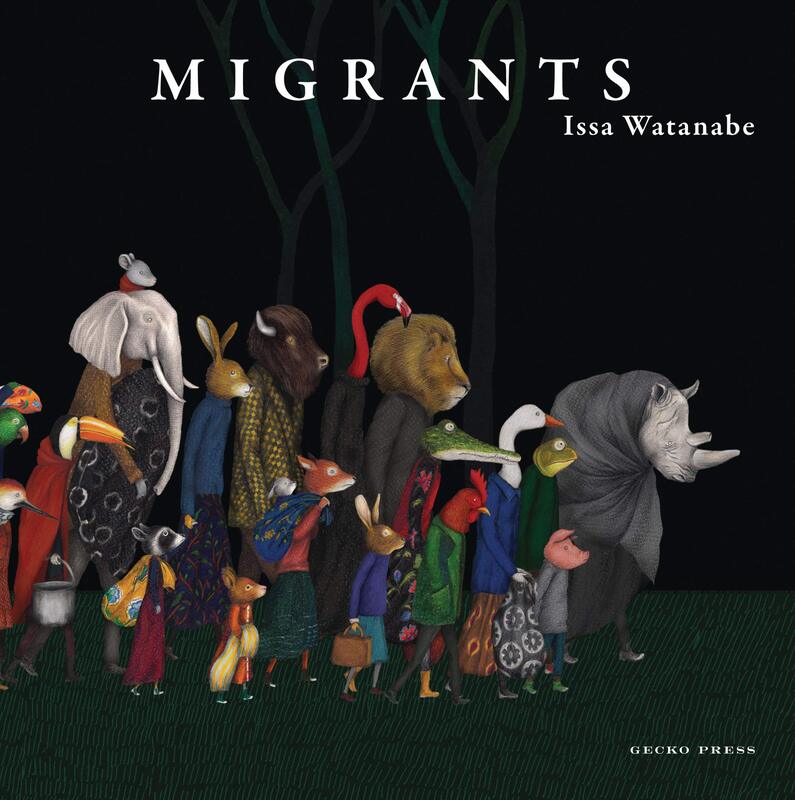

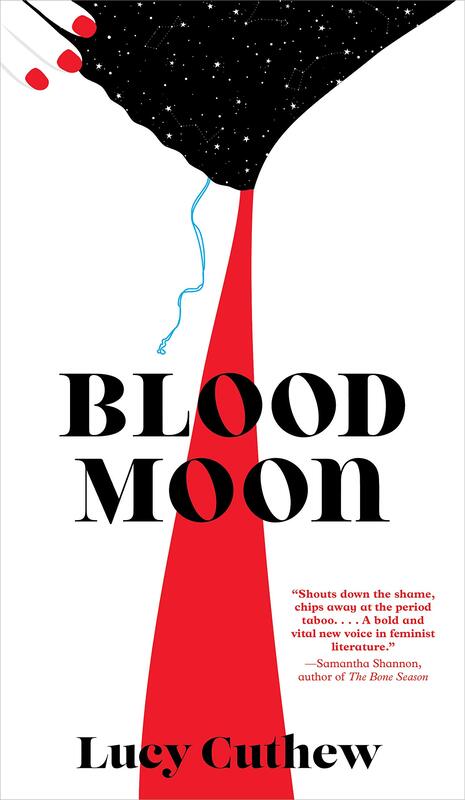

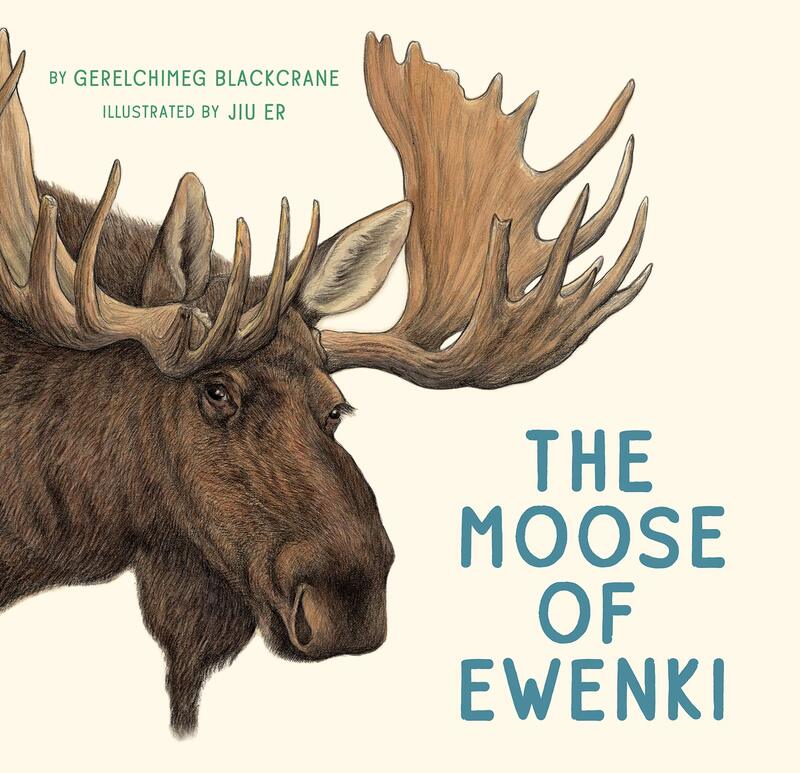

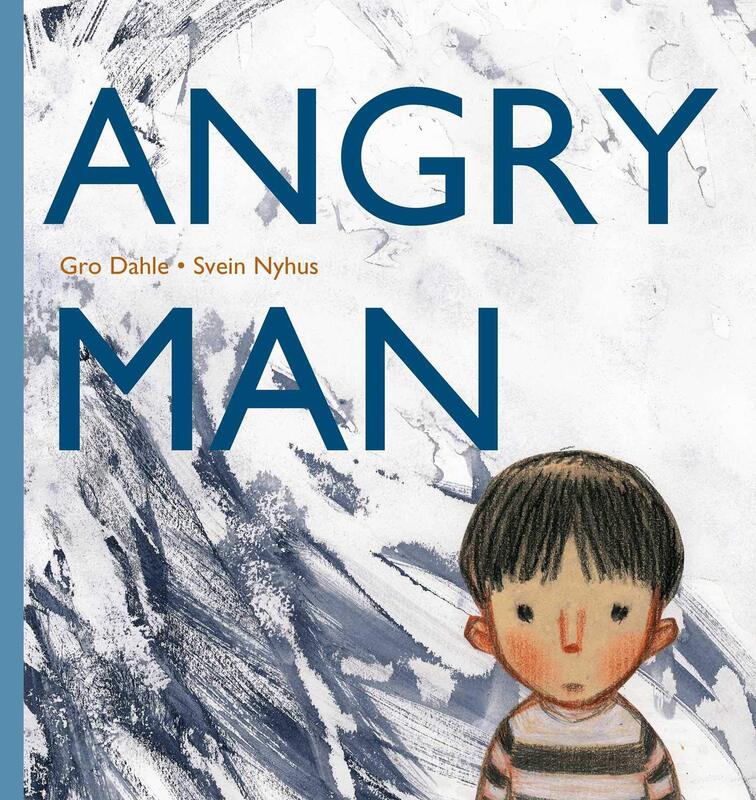

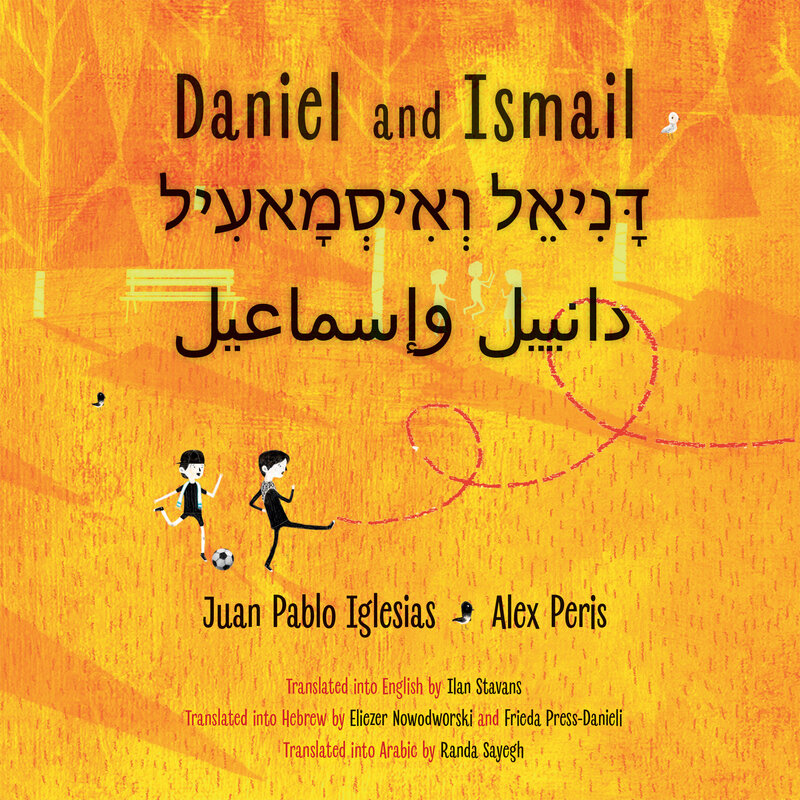

(Book covers are organized by younger-to-older audience gradation.)

(civil, border, global, & cultural)

(civil, border, global, & cultural)

(personal, biographical, cultural, geographical, historical, traditional, philosophical, intergenerational, visual, epistolary)

(accentuating humans’ relationships with the natural world)

(Playful approaches to familiar topics, how play and curiosity can foster connections and community, and the role of imagination in creating new possibilities and realities, benefits of unexpected journeys)

|

2022 OIB Bookmark & Annotations

|

2021 OIB Bookmark & Annotations

|

2020 OIB Bookmark & Annotations

|

Making Friends and Building Community through Play |

Engaging Math Explorations |

|

|

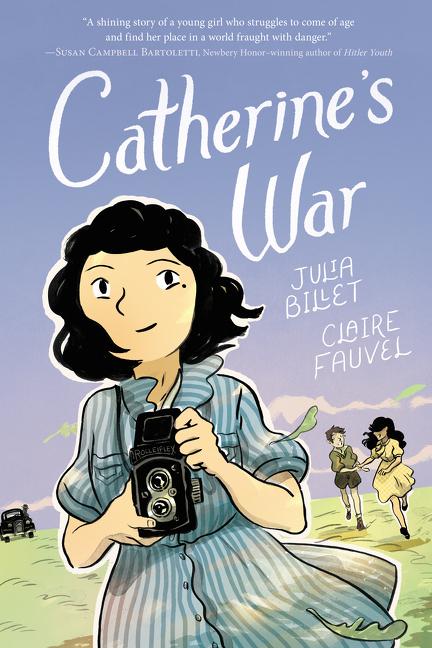

WWII and Holocaust Survivor Stories |

Family Separations |

|

|

For more information about OIB books and USBBY, please join us in Nashville, Tennessee, March 4-6, 2022 for USBBY’s Regional Conference.

References

Rabbe, C. (2016). “Hello, dear enemy! Picture books for peace and humanity.” Bookbird: A Journal of Children’s LIterature, 54(4), 57-61.

Rabbe, C. & von Merveldt, N. (2018). “Welcome to the new home country Germany: Intercultural projects of the International Youth Library with refugee children and young adults.” Bookbird: A Journal of Children’s LIterature, 56(3), 61-65.

Jennifer M. Graff is an Associate Professor in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia, is a former CLA President and Member for 15+ years.

By Erin Knauer and Katie Caprino

In this blog post, we will share our definition of standards-based virtual libraries, how they can help support preservice teachers as they progress in their development as teachers, and tips for how to build these virtual libraries.

What are Standards-Based Virtual Libraries?

Literacy standards support the content through academic vocabulary, knowledge building, and engaging in literacy practices as they pertain to the academic grade level of students. Standards-based virtual libraries function as a display of books that are age-appropriate, relevant, and applicable to the standards intended for a literacy-enriched classroom.

How Creating Standards-Based Virtual Libraries Help Preservice Teachers?

During the pandemic, Katie had her language and literacy development students create YouTube videos of themselves reading books aloud and link these videos to the cover images. She thought that having her students engage in what so many teachers were doing during the height of the remote learning moment gave her students an authentic assignment. However, as copyright permissions about recorded read-alouds have since changed, Katie no longer requires students to link a read-aloud video. (Preservice teachers could still link to publisher-approved read-alouds that do not infringe on any copyright matters.)

Still, virtual libraries serve an important role in providing ideas for texts that would make excellent in-class read-alouds. Additionally, these libraries provide a fun way for preservice teachers to organize and arrange books while learning about how to support their students meet state literacy standards and skills. It puts learning about standards in the context of authentic literature. In addition, they provide ideas for books that could be used in small center exploration and can be used as a means by which to provide parents ideas about texts that they may want to read to their children outside of the classroom. Preservice teachers can customize their library to be academically engaging to their students and encourage ample exploration.

How Does a Standards-Based Virtual Library Look?

Below is a snapshot of a standards-based virtual library Erin created for Katie’s course. Kid-friendly and visually-appealing, Erin’s library includes an original Bitmoji figure and the covers of ten contemporary picture books she selected. Creating a Bitmoji helps preservice teachers envision themselves in the role of teacher and makes the virtual library more personal. If you would like more information about virtual libraries, please see Minero’s Edutopia article “How to Create a Digital Library That Kids Eat Up.”

Each of the books below relate to a specific first-grade Pennsylvania state standard.

| Figure 1. Standards-Based Virtual Library by Erin Knauer (Images from Google. Bitmoji created with Bitmoji app.) |

What types of books are featured in Erin's Virtual Library?

In the assignment, students were asked to select contemporary picture books (written within the last 10 years) that would help them teach literacy standards at a particular grade level. The chart below documents two books that are featured in Erin's standards-based virtual library to show the types of books that could be included. We acknowledge that each state has its own literacy standards, so rather than identify specific standards met, we consider the overarching literacy skills that could be met by each.

|

Book Cover

|

Title & Author

|

Quick Summary

|

Literacy Skills Met

|

|

Ada Twist. Scientist by Andrea Beaty (2017)

|

Through the life of young Ada Marie Twist, we see a character who is so full of questions that her parents struggle to keep up with answers. When Ada is presented with a puzzling problem, she experiments and uses scientific reasoning to try and figure it out, leaving chaos in her wake.

|

|

|

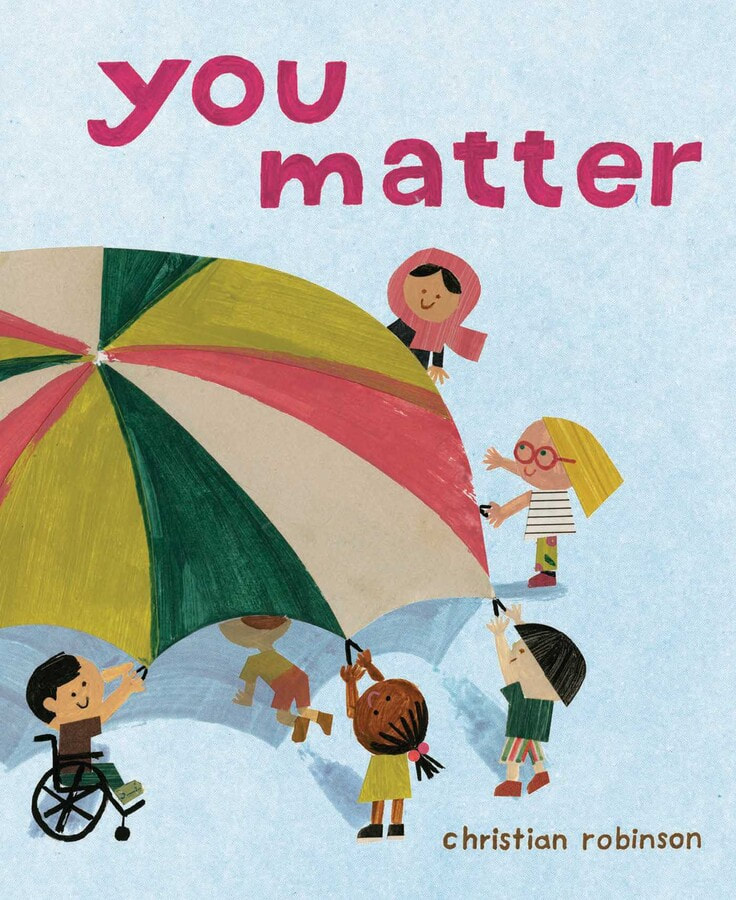

You Matter by Christian Robinson (2020)

|

This picture book enunciates that all beings have value, from the smallest bug under the lens to a dinosaur away from its group, whether you succeed or fail, regardless of race or age, even when you feel alone.

|

|

After completing the assignment, Erin considered five tips she would recommend to fellow preservice teachers.

|

Books in

|

The authors would like to thank the Mellon Foundation for funding for this blog post.

Katie Caprino is an Assistant Professor of PK-12 New Literacies at Elizabethtown College. She taught middle and high school English in Virginia and North Carolina. She holds a BA from the University of Virginia, a MA from the College of William and Mary, a MA from Old Dominion University, and a Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Katie researches and presents on children’s, middle grades, and young adult literature; the teaching of writing; and incorporating technology into the literacy classroom. You can follow her on Twitter at @KCapLiteracy and visit her book blog at katiereviewsbooks.wordpress.com. She is a member of the Children’s Literature Assembly.

By Amina Chaudhri and Julie Waugh, on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse

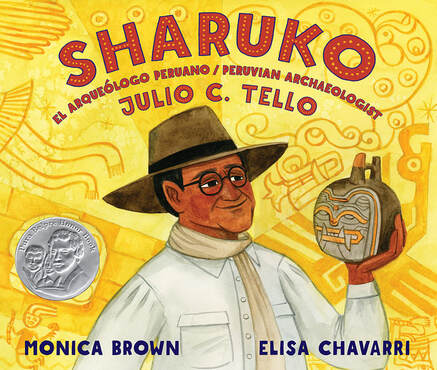

This entry of The Biography Clearinghouse offers a variety of teaching and learning experiences to use with Sharuko: el Arqueólogo Peruano/Peruvian Archaeologist, a bilingual biography of Julio C. Tello, written by Monica Brown, and illustrated by Elisa Chavarri. In addition to a recorded interview with the author in which she discusses her research process and the craft of creating picturebook biographies, we include suggestions for learning about Peruvian textiles, the Quechua language, and variations on the trait of bravery. Below are two ideas inspired by Sharuko.

Connecting the Past and the Present

Begin by reading Sharuko aloud with students, inviting them to note the chronology of his life, from boy to researcher, the people who supported him along the way, and his connections to history as depicted in the text and images. In analyzing this biography, teachers might scaffold students’ understandings of:

- The character traits that Monica Brown includes in her representation of Julio C. Tello.

- The integration of history through text and image.

- The linear chronology on which the narrative rests, like an annotated timeline.

Thinking Like an Archeologist

The teaching and learning suggestions below are designed for teachers to plan experiences that involve thinking like an archeologist:

If you have 1-2 hours . . . |

If you have 1-2 days . . . |

If you have 1-2 weeks . . . |

No matter the time period being studied - historical or contemporary - the close examination of artifacts involves honing keen observational and critical thinking skills. Teachers can present students with a selection of objects or parts of objects and invite them to examine them to see what stories they reveal. As an extension activity, students can bring their own artifacts from home, adding to the archaeological analysis. |

Invite students to learn enough about an artifact (and its discoverer) to create a museum exhibit about the artifact. (Julio C. Tello may have done this for his found artifacts.) Use the Smithsonian Learning Lab Museum Descriptions as mentor texts to help students discover what they may want to include in a museum description of their own. |

Combine archeological museum exhibits to make a museum for learning in your school community. Invite other classes, parents, and the larger community. Create an archeological museum of the “future.” Invite students to pretend they are 500 years in the future and challenge them to create a museum showcasing archeological artifacts that showcase school life in the 2020s. This will invite them to think deeply and use the skills and strategies of an archeologist. Which artifacts in their classroom may survive for that long? How could you write about these artifacts to describe them for someone who does not recognize them? Create museum exhibits and a museum. Invite outside learners. |

Julie Waugh shares a 4th grade teaching position at Zaharis Elementary in Mesa, AZ and serves as an Inquiry Coach for Mesa Public Schools. She delights in the company of children surrounded and inspired by books. A longtime member of NCTE, and an enthusiastic newer member of CLA, Julie is a former committee member of NCTE's Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction for Children.

Authors:

CLA Members

Supporting PreK-12 and university teachers as they share children’s literature with their students in all classroom contexts.

The opinions and ideas posted in the individual entries are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of CLA or the Blog Editors.

Blog Editors

contribute to the blog

If you are a current CLA member and you would like to contribute a post to the CLA Blog, please read the Instructions to Authors and email co-editor Liz Thackeray Nelson with your idea.

Archives

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

October 2023

September 2023

August 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

Categories

All

Activism

Advocacy

African American Literature

Agency

All Grades

American Indian

Antiracism

Art

Asian American

Authors

Award Books

Awards

Back To School

Barbara Kiefer

Biography

Black Culture

Black Freedom Movement

Bonnie Campbell Hill Award

Book Bans

Book Challenges

Book Discussion Guides

Censorship

Chapter Books

Children's Literature

Civil Rights Movement

CLA Auction

CLA Breakfast

CLA Expert Class

Classroom Ideas

Collaboration

Comprehension Strategies

Contemporary Realistic Fiction

COVID

Creativity

Creativity Sponsors

Critical Literacy

Crossover Literature

Cultural Relevance

Culture

Current Events

Digital Literacy

Disciplinary Literacy

Distance Learning

Diverse Books

Diversity

Early Chapter Books

Emergent Bilinguals

Endowment

Family Literacy

First Week Books

First Week Of School

Garden

Global Children’s And Adolescent Literature

Global Children’s And Adolescent Literature

Global Literature

Graduate

Graduate School

Graphic Novel

High School

Historical Fiction

Holocaust

Identity

Illustrators

Indigenous

Indigenous Stories

Innovators

Intercultural Understanding

Intermediate Grades

International Children's Literature

Journal Of Children's Literature

Language Arts

Language Learners

LCBTQ+ Books

Librarians

Literacy Leadership

#MeToo Movement

Middle Grade Literature

Middle Grades

Middle School

Mindfulness

Multiliteracies

Museum

Native Americans

Nature

NCBLA List

NCTE

NCTE 2023

Neurodiversity

Nonfiction Books

Notables

Nurturing Lifelong Readers

Outside

#OwnVoices

Picturebooks

Picture Books

Poetic Picturebooks

Poetry

Preschool

Primary Grades

Primary Sources

Professional Resources

Reading Engagement

Research

Science

Science Fiction

Self-selected Texts

Small Publishers And Imprints

Social Justice

Social Media

Social Studies

Sports Books

STEAM

STEM

Storytelling

Summer Camps

Summer Programs

Teacher

Teaching Reading

Teaching Resources

Teaching Writing

Text Sets

The Arts

Tradition

Translanguaging

Trauma

Tribute

Ukraine

Undergraduate

Using Technology

Verse Novels

Virtual Library

Vivian Yenika-Agbaw Student Conference Grant

Vocabulary

War

#WeNeedDiverseBooks

YA Lit

Young Adult Literature

RSS Feed

RSS Feed