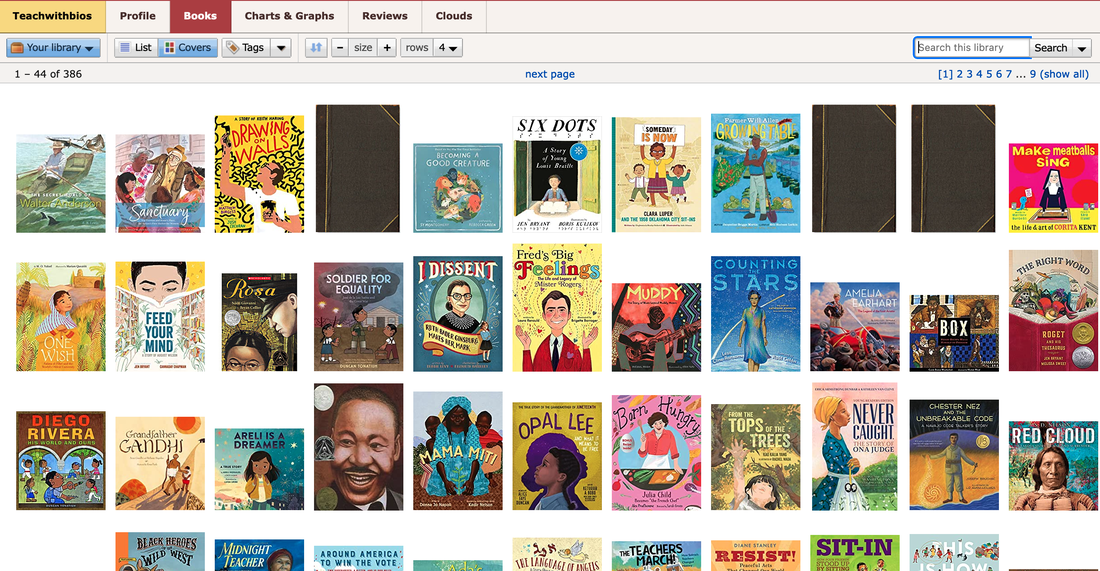

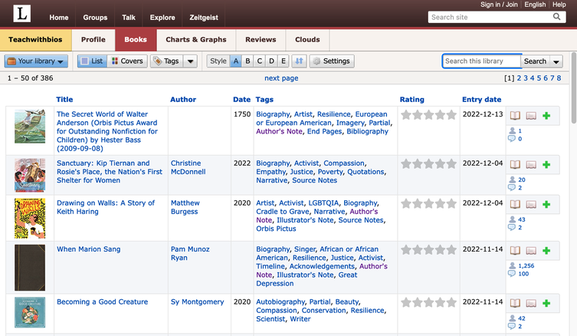

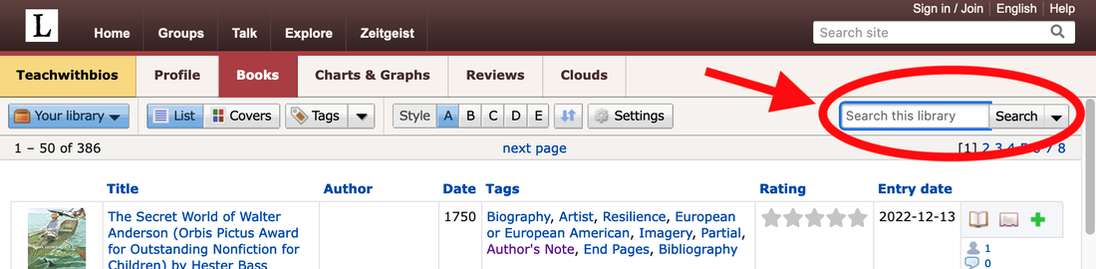

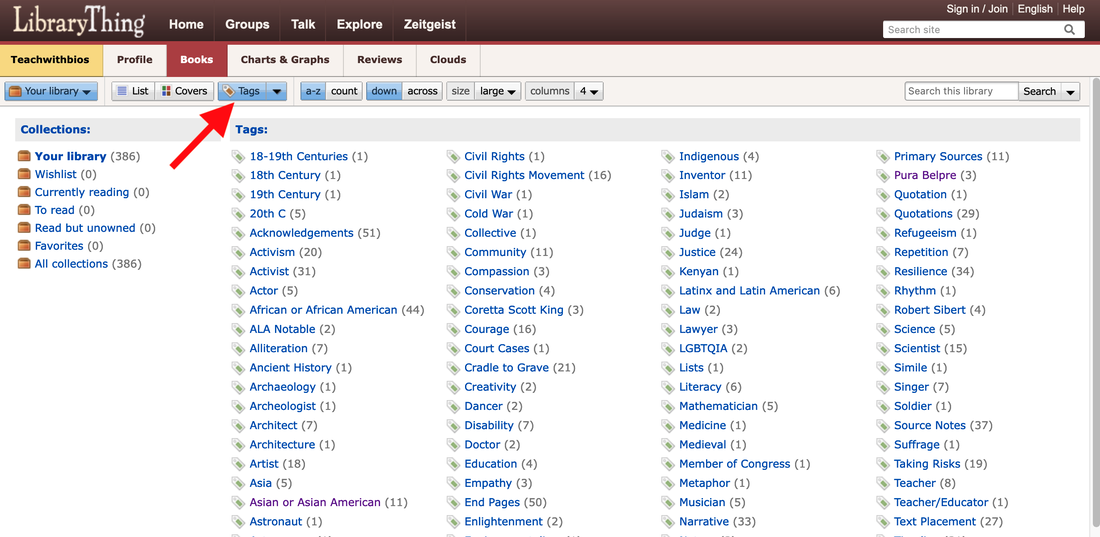

By Xenia Hadjioannou & Mary Ann Cappiello on behalf of the Biography Clearinghouse  Wondering how to find and curate biographies suited to the interests of your students or to your curricular needs? Frustrated by a piecemeal approach, cross-referencing booklists, award lists, and Google searches? The Biography Clearinghouse has a year end gift for you! We have created a collection of biographies for young people on LibraryThing, an online book cataloging service. The collection makes use of “tags” with which users can use to guide and focus their searches. This continually updated collection is intended as a tool for educators of all subjects and age groups, librarians, and anyone else who enjoys and works with biographies. We are busily tagging the books in our collection and will continue to add and tag more titles! The best part about it? You can access our collection for free and without having to sign up for an account. You can search the collection by theme, literary elements, geographic location, format feature, profession/discipline, etc. To learn how to access, navigate, and search through the Biography Clearinghouse Collection review the information below. How do I access the Biography Clearinghouse Collection?

Simply go to https://www.librarything.com/catalog/Teachwithbios. There you will see our entire catalog listing. In the “Tags” column you will see all the tags assigned to each book by members of the Biography Clearinghouse.

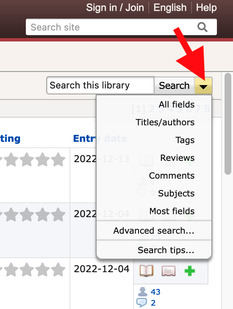

How do I search through your catalog?

Clicking on a tag will produce a listing of all books in our catalog we have annotated with it. Have any questions? Biographies to add to our collection? Suggested tags? Please email us at teachwithbios@gmail.com. We’d love to hear from you. Xenia Hadjioannou is an Associate Professor of Language and Literacy Education at the Berks campus of Penn State University where she teaches and works with preservice teachers through various courses in language and literacy methodology. Xenia is the co-author of Translanguaging for Emergent Bilinguals. She is the Vice President and Website Manager of the Children's Literature Assembly, and a co-editor of The CLA Blog. Mary Ann Cappiello is a Professor of Language and Literacy at Lesley University, where she teaches courses in children’s literature and literacy methods. For twelve years, she blogged about teaching with children’s literature at The Classroom Bookshelf. She is a former chair of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8. Mary Ann is the coauthor of Text Sets in Action: Pathways Through Content Area Literacy (2021). By Emmaline Ellis, Laurie Esposito, and Jennifer SlagusIn response to an increase in attempts to ban and challenge various children’s and young adult books, the topic of this year’s Children’s Literature Assembly Student Committee (CLA-SC) Annual Student Webinar was “Book Bans: Who, How, and Why?” As a committee with diverse experiences, interests, and roles in the field of children’s literature, the CLA-SC members find these movements to be particularly concerning, as the targeted books are often those that feature characters who are LGBTQIA+, Black, or Hispanic. While some book challenges have received pushback, many others have been successful. These decisions made us wonder - how do books become banned? What is the reasoning supporting these bans? And, who are the decision-makers behind book bans? These burning questions were the guiding focus of this year’s CLA-SC Student Webinar. In order to learn more about the decision-making processes behind book bans, we enlisted the expertise of four esteemed panelists, all of whom are CLA Committee or Board Members. In this post, we summarize and highlight each panelists’ professional or personal experiences and insight as they relate to book bans, and conclude by sharing the informative and helpful resources shared throughout the Webinar. CLA Members can access a video recording of the webinar within the members-only section of the CLA website. Dr. Rachel Skrlac Lo

Our first panelist shared the story of a book challenge in her suburban Philadelphia school district. Dr. Rachel Skrlac Lo, Assistant Professor of Education at Villanova University and parent of a child in the district, described the district’s response when a fellow parent challenged Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer. In violation of its own protocol, the district removed the book from the high school library pending review by an anonymous ad hoc committee. Various district stakeholders justified the challenge with concerns about potentially harmful psychological effects and age appropriateness. Dr. Skrlac Lo countered these unsubstantiated concerns with empirical data on the harm under-representation in schools causes LGBTQIA+ youth. Although Gender Queer was ultimately returned to the library’s shelves in June 2022, Dr. Skrlac Lo pointed out that a single complaint rendered the book inaccessible to all students for nearly an entire academic year. In concluding her presentation, Dr. Skrlac Lo focused on ways in which we can act against book challenges and bans in schools. She encouraged us to share our expertise through engagement in public discourse. For example, we could join community groups, attend committee meetings, write to legislators, and write op-ed pieces for local publications. Perhaps most importantly, she urged us to “resist and push against” deficit narratives as we listen to and support members of groups targeted by censorship efforts. Breakout Quote for Dr. Skrlac Lo: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

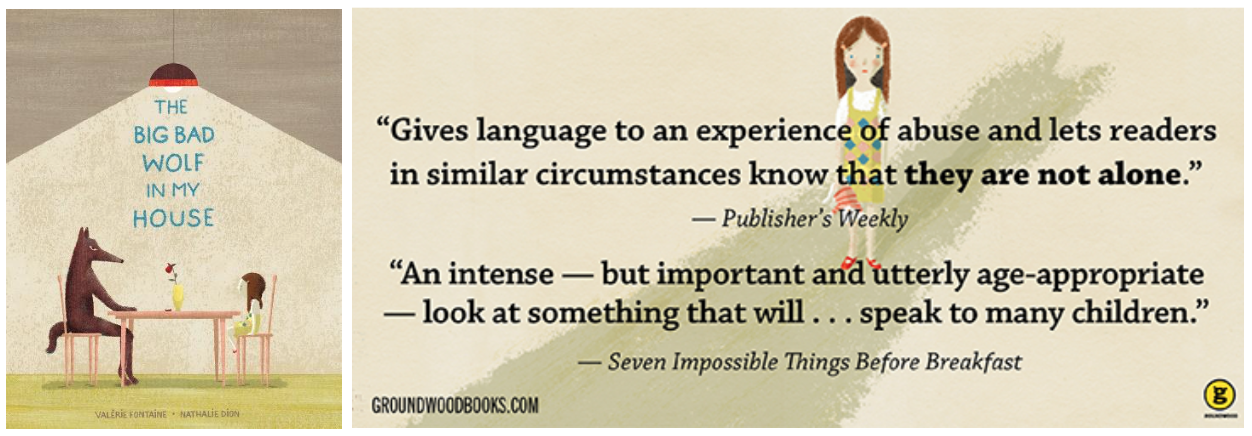

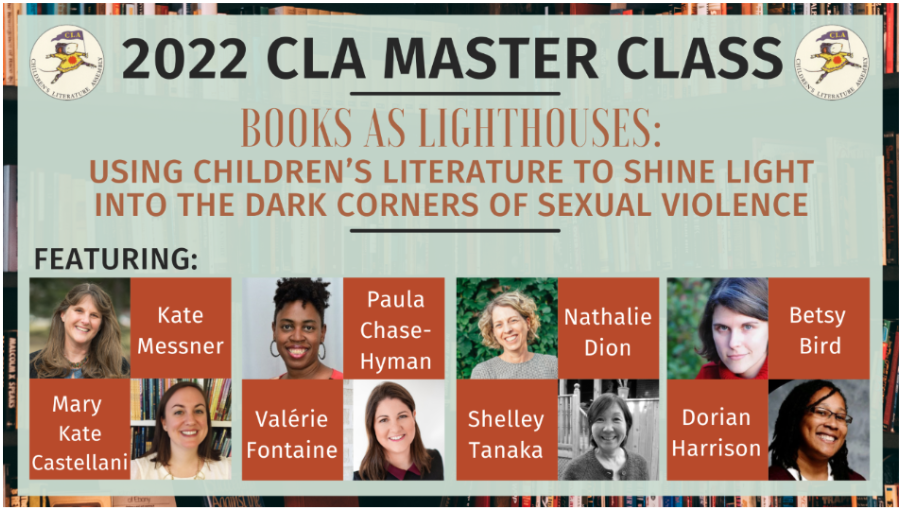

Valérie Fontaine is the author of The Big Bad Wolf in My House, her first book to be translated into English. A Quebec writer and French-language author, Valérie has published more than thirty-five books for young people. She frequently visits schools to share her books with children and teachers. Each week, she can be found reading stories to children live on Facebook. Valérie shares that she “loves writing books as much as she loves reading and talking about them” (https://houseofanansi.com).

|

|

Nathalie Dion is the illustrator of The Big Bad Wolf in My House. An award-winning freelance illustrator based in Montreal, she studied Design Arts at Concordia University. Nathalie exhibits her work in art galleries and museums, and she works on commissioned assignments in both editorial and children’s book illustration. Her favorite artistic tools are her Cintiq tablet and her numeric paintbrushes.

|

|

Shelley Tanaka is the translator of The Big Bad Wolf in My House. She is a Canadian award-winning author, translator, and editor. She has written and translated more than thirty books for children and young adults. Among the many awards that Shelley has won are the Orbis Pictus Award, the Mr. Christie’s Book Award, and the Science in Society Book Award. Shelley teaches at the Vermont College of Fine Arts in the MFA Program in Writing for Children and Young Adults.

|

|

Betsy Bird, the panel moderator, is a children’s author, librarian, podcaster, blogger, and reviewer. She is the Collection Development Manager of Evanston Public Library and the former Youth Materials Specialist of New York Public Library. Betsy is a frequent blogger at the School Library Journal site: A Fuse #8 Production, where she has reviewed a number of children’s books that address the topic of this master class. She also reviews books for Kirkus and The New York Times and hosts Fuse 8 n’ Kate, a podcast with her sister about classic children’s books.

|

|

Dr. Dorian Harrison, the panel discussant, is an Assistant Professor at The Ohio State University at Newark. With over 15 years of experience in education, she teaches foundational and licensure courses in literacy at the undergraduate and graduate level. Dr. Dorian Harrison’s research explores how equity in literacy education is enacted, paying particular attention to the ways communities of learners are challenging deficit views and practices. Her research is aimed at not only improving classroom practice but also restructuring how institutions prepare future educators to engage with diverse populations of students and communities.

|

The following overriding questions will guide the session: How might books with dark subject matter foster hope in readers? And, how might teachers and teacher educators facilitate reader engagement with these vital books? We hope that attendees will leave the session with a more nuanced understanding of the shifting landscape of children's literature relative to the #MeToo movement, along with a deeper level of comfort using these books in classrooms, especially in light of the turbulent times that teachers and teacher educators inhabit relative to censorship.

de León, C. (2020, June 17). Why more children's books are tackling sexual harassment and abuse. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/17/books/childrens-books-middle-grade-metoo-sexual-abuse.html

Maughan, S. (2020, April 13). Eye on middle grade: Editors discuss some of the latest developments in the category. Publishers Weekly, 23-21. Retrieved from https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/childrens/childrens-book-news/article/83006-eye-on-middle-grade-spring-2020.html

Robillard, C. M., Choate, L., Bach, J., & Cantey, C. (2021). Crossing the line: Representations of sexual violence in middle-grade novels. The ALAN Review, 49(1), 33-47.

Resources

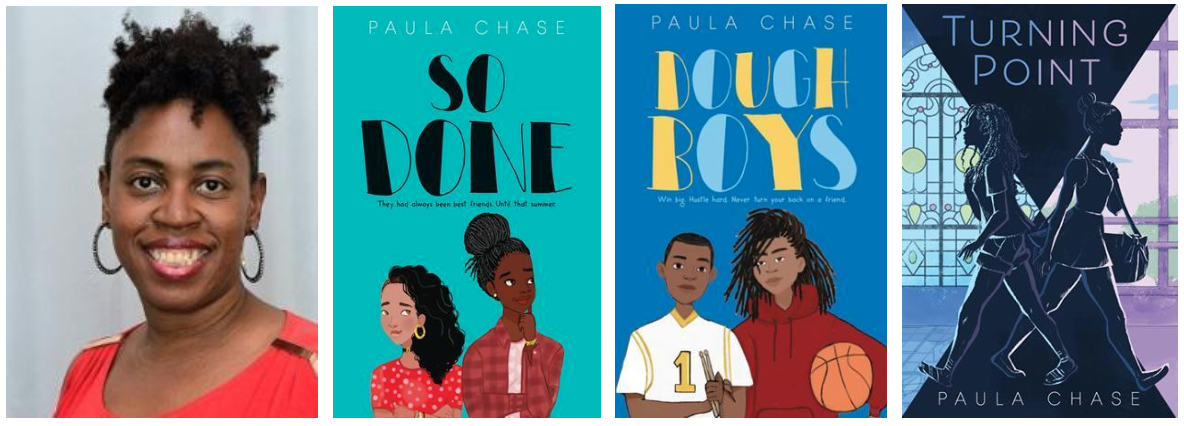

Paula Chase-Hyman’s Interview with Reading Middle Grade Blog.

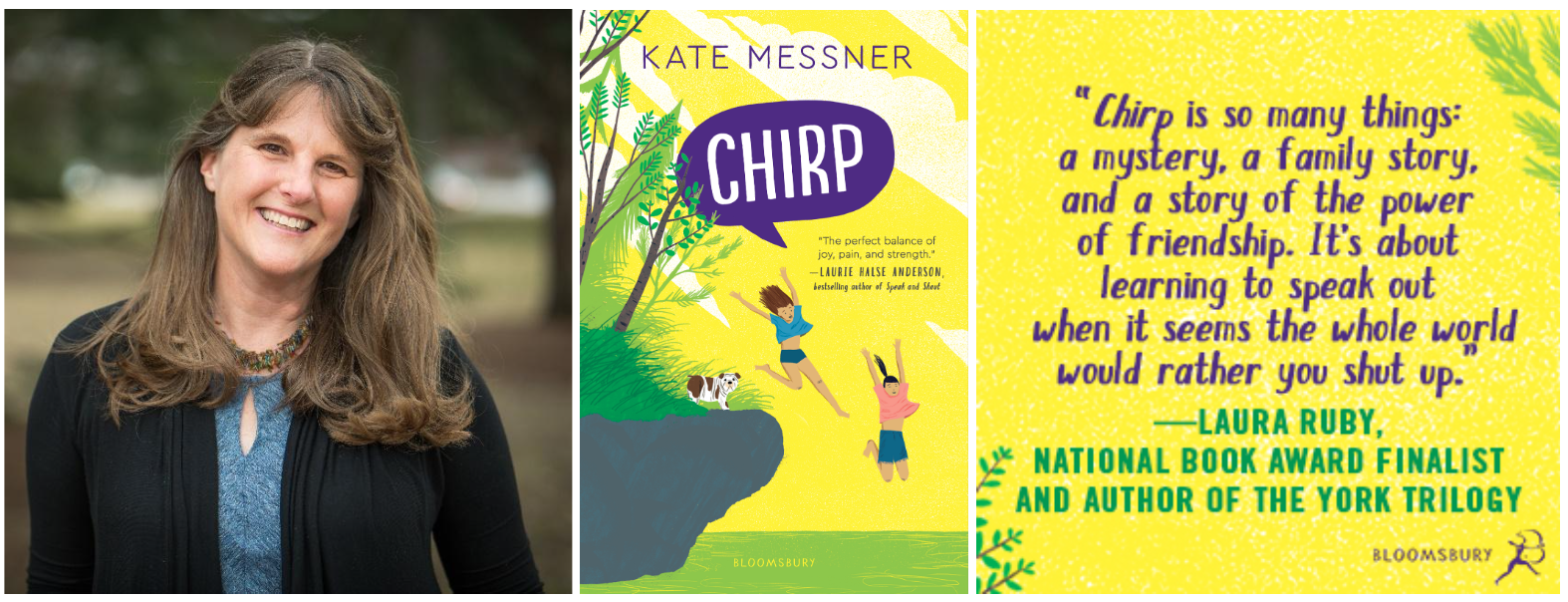

Kate Messner’s Interview with BookPage

Valérie Fontaine’s Interview with Foreword Reviews

Nathalie Dion’s Feature in Canadian Children’s Book News

Shelley Tanaka’s Interview with Cynthia Leitich Smith at Cynsations

S. Adam Crawley (he/him) is an Assistant Teaching Professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder. His current roles with CLA include serving as a Board Member and Master Class Co-Chair. In addition, he is the treasurer of NCTE’s Genders and Sexualities Equalities Alliance (GSEA).

Sara K. Sterner (she/her) is an Assistant Professor at Cal Poly Humboldt and the Leader of the Liberal Studies Elementary Education Program in the School of Education. Her current roles with CLA include serving as a Board Member and Master Class Co-Chair.

by Andrea M. Page

| The National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) November conference is here! With so many fantastic sessions to attend, I’d like to shine a light on several Indigenous/First Nation/Native creatives who will be presenting at this year’s conference. Did you know that according to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC), of the estimated 3427 books published in 2021 in the U.S. by Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) authors, only 60 books, or 0.017% were written by Native authors? An additional 74 books about Indigenous people and their culture were written by non-Natives. The numbers are slowly rising since the first detailed set of data released by the CCBC in 2002, when only six Native authors published books, yet at that time, 64 books were published about Indigenous people and/or culture written by non-Natives. Educators know how important it is to recognize and appreciate diversity in children’s literature, and ensure children have access to books and characters that represent authentic voices. No group is more diverse than Indigenous cultures across the globe. In the United States alone, there are nearly 600 federally recognized tribes, all with similar traditions and values but very different cultures based on their geographic locations. Each tribe has its own worldview. |

|

Fall is a time of harvest and celebration. After the hard work of planting seeds, BIPOC voices are important, new ideas seed new experiences laboring and growing, Authentic Indigenous voices are taking root and thriving and reaping the harvest, Fresh Native Creatives, values, culture, and humor are plenty it is a time to feast and celebrate. |

|

THURSDAY Darcie Little Badger A.28 Shining a Light on Rural YA Literature: Presenting the Winners of the Whippoorwill Award for Rural Young Adult Literature Thursday, 09:30 - 10:45 Carole Lindstrom B.04 Birds Aren’t Real: Literature as Truth and Light in Dark Times Thursday, 11:00 - 12:15 FRIDAY Traci Sorell E.31 Possibilities of Poetry: Excavating and Exploring Identity in the Elementary Classroom Friday, 09:30 - 10:45 Angeline Boulley F.06 Constellations and Not a Single Star: Shining and Rising Native Voices on Collaboration and Writing Truths Friday, 11:00 - 12:15 Carole Lindstrom F.06 Constellations and Not a Single Star: Shining and Rising Native Voices on Collaboration and Writing Truths Friday, 11:00 - 12:15 Traci Sorell F.06 Constellations and Not a Single Star: Shining and Rising Native Voices on Collaboration and Writing Truths Friday, 11:00 - 12:15 Laurel Goodluck F.06 Constellations and Not a Single Star: Shining and Rising Native Voices on Collaboration and Writing Truths Friday, 11:00 - 12:15 Traci Sorell G.04 Bring the Light In: Children’s Literature for Truth Telling Friday, 12:30 - 13:45 Monique Gray Smith H.04 Braiding Sweetgrass for Young Adults: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants with Adapter Monique Gray Smith Friday, 14:00 - 15:15 Angeline Boulley HI.01 High School Matters—Learning Liberated: Reading, Writing, and Discussion Grounded in Multimodal Pedagogies Friday, 14:00 - 16:45 Traci Sorell H.34 Teaching with the 2022 Charlotte Huck and Orbis Pictus Award Books ROOM 204-A 14:00-15:15 SATURDAY Traci Sorell K.10 #DisruptTexts Now More Than Ever Saturday, 11:00 - 12:15 Angeline Boulley K.37 Teaching Young Adult Literature: Creating Space to Pursue Light and to Dream Saturday, 11:00 - 12:15 Joy Harjo L.30 #TeachLivingPoets and US Poet Laureate Joy Harjo Present Living Nations, Living Words, and Teaching Native Nations Poets Saturday, 12:30 - 13:45 Traci Sorell M.14 Connecting through Story: The Transformative Power of Daily Picture Book Read-Alouds Saturday, 14:45 - 16:00 Arigon Starr M.14 Connecting through Story: The Transformative Power of Daily Picture Book Read-Alouds Saturday, 14:45 - 16:00 Jen Ferguson N.08 Countering Harmful Media Narratives with Young Adult Literature Saturday, 16:15 - 17:30 |

NCTE 2022 Native Authors Darcie Little Badger (Lipan Apache). Author of Elatsoe and A Snake Falls to Earth. Website: darcielittlebadger.wordpress.com Carole Lindstrom (Anishinabe/Metis, tribally enrolled with the Turtle Mountain Band of Ojibwe) Author of Girls Dance, Boys Fiddle, and We are Water Protectors. Website: carolelindstrom.com Traci Sorell (Cherokee Nation citizen) Author of We are Grateful: Otsaliheliga, At the Mountain’s Base, Powwow Day, Classified: The Secret Career of Mary Golda Ross, Cherokee Aerospace Engineer, and Contenders: Two Native Baseball Players, One World Series Website: tracisorell.com Monique Gray Smith (Cree, Lakota and Scottish) Author of My Heart Fills With Happiness, You Hold Me Up, When we are Kind, Lucy and Lola and I Hope, Tilly: A Story of Hope and Resilience, Braiding Sweetgrass, and Tilly and the Crazy Eights Website: moniquegraysmith.com Angeline Boulley (enrolled member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians) Author of Firekeeper's Daughter and Warrior Girl Unearthed. Website: angelineboulley.com Laurel Goodluck (Mandan and Hidatsa from the prairies of North Dakota, and Tsimshian from a rainforest in Alaska). Author of Forever Coursins. Fortcoming books: Rock your Mocs and Too Much Website: laurelgoodluck.com Joy Harjo (member of the Mvskoke Nation and belongs to Oce Vpofv (Hickory Ground)). Author of An American Sunrise, The Good Luck Cat and For a Girl Becoming. Website: joyharjo.com Arigon Starr (enrolled member of the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma) . Illustrator of Super Indian and Tales of the Mighty Code Talkers Website arigonstarr.com Jen Ferguson (Michif/Métis) Author of The Summer of Bitter and Sweet Website: jenfergusonwrites.com |

Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC)

https://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/literature-resources/ccbc-diversity-statistics/books-by-and-or-about-poc-2018/

by Angela Wiseman & Ally Hauptman (2022 Co-Chairs)

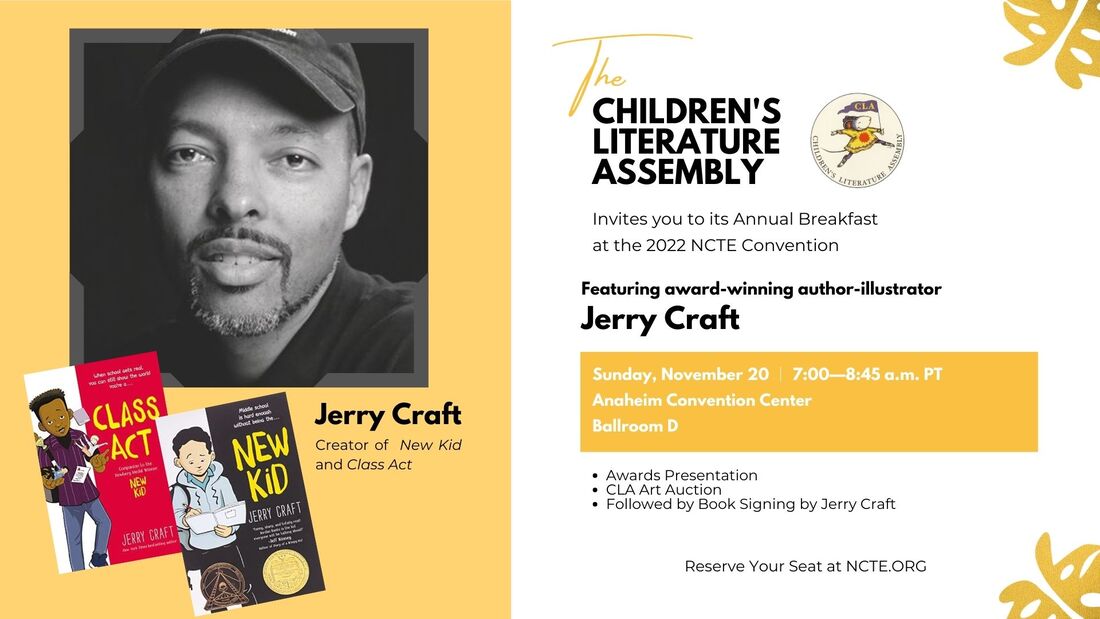

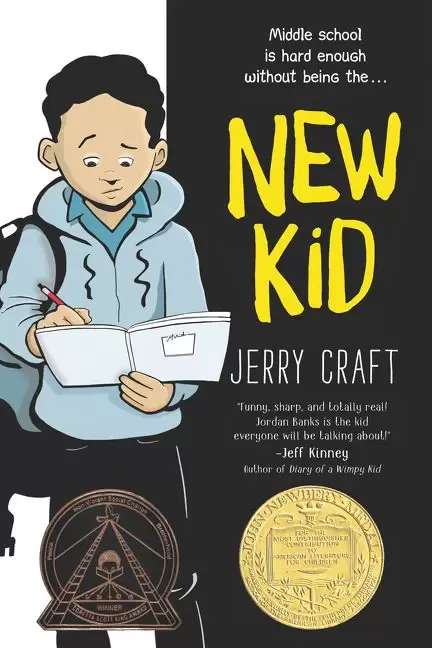

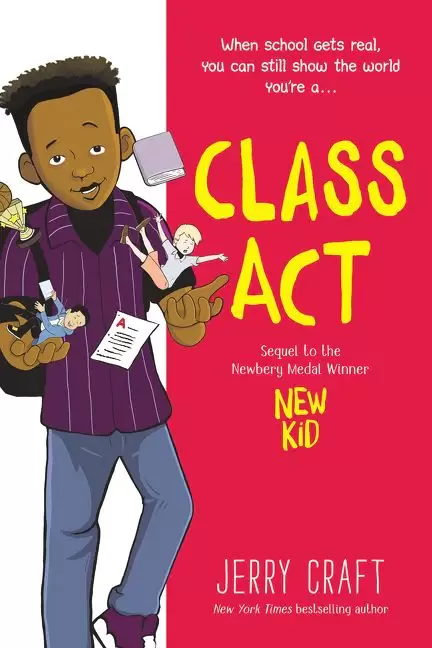

The CLA breakfast is not to be missed! As you have seen in other blog posts, we will present awards, have an art auction and book raffle, and then Jerry Craft will speak and sign books afterwards! You need a ticket to the CLA Breakfast to attend. If you have already registered for the NCTE conference, but would like to purchase a ticket to the breakfast, the easiest way to do this is to call NCTE directly at (877) 369-6283.

We were first introduced to his work when we read New Kid, which was published in 2019. New Kid is part of a trilogy; Class Act is the second book and the third will be released in the near future. This fantastic book about Jordan Banks describes his experiences dealing with life as an adolescent while attending a private school where he doesn’t always fit in. He’s one of the only students of Color at this school and experiences prejudice and racism as he realizes how both race and socioeconomic factors impact the way people treat each other. Jerry Craft is motivated to show realistic portrayals of children in his books, but he also really wants children, particularly children of Color, to see themselves in his stories.

| Before Jordan Banks, Jerry Craft wrote the comic strip Mama’s Boyz, which features the Porter family. It depicts the experience of Pauline Porter, a mother who is single-parent to two teenaged sons named Tyrell and Yusuf. While depicting real life experiences of a family, it was important that he had characters that he could imagine his own sons reading and relating to. If you visit his website, the first thing you see next to his profile and books is a quote that says “I make the books I wish I had when I was a kid.” |

Angela Wiseman and Ally Hauptman

Angela Wiseman is a CLA Board Member and is co-chair of the 2022 CLA Breakfast Committee. She is an associate professor of literacy education at North Carolina State University.

by Peggy Rice and Ally Hauptman representing the Ways and Means Committee

|

Each year at the NCTE Conference, the Children’s Literature Assembly hosts a breakfast. It is one of our favorite events of the conference because we get to listen to an author speak about their work and we get to see the gorgeous artwork available in the silent auction. This year our speaker is Jerry Craft, Newbery winner and author of New Kid and Class Act. Jerry is also contributing a piece of art to the auction!

The Ways and Means Committee spends a better part of the year communicating with children’s picture book authors/illustrators about donating artwork to support the major goals of our organization. CLA is committed to promoting high quality children’s books in classrooms and supporting research focused on the importance of children’s literature. |

Ways and Means Committee

Raven Cromwell Michelle Hasty Ally Hauptman Mary Lee Hahn Rachelle Kuehl Marion Rocco Peggy Rice |

Elizabeth Erazo Baez

Amanda Calatzis

Alina Chau

|

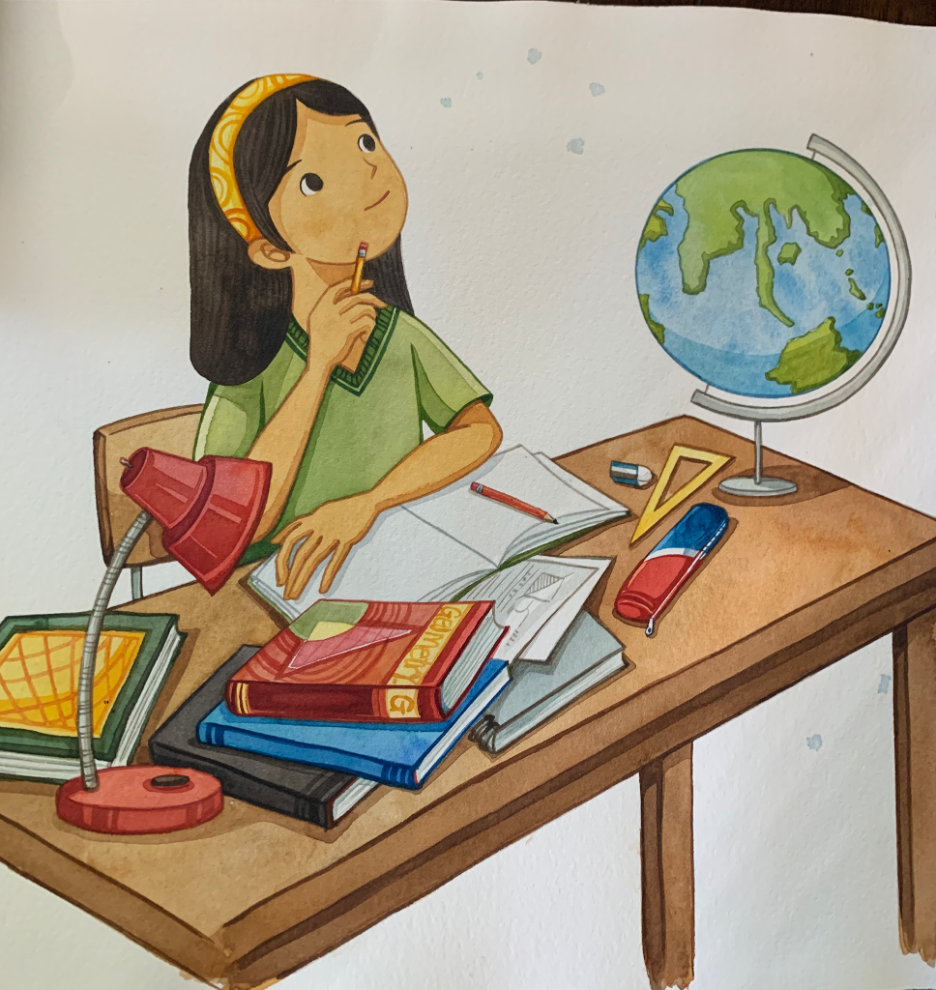

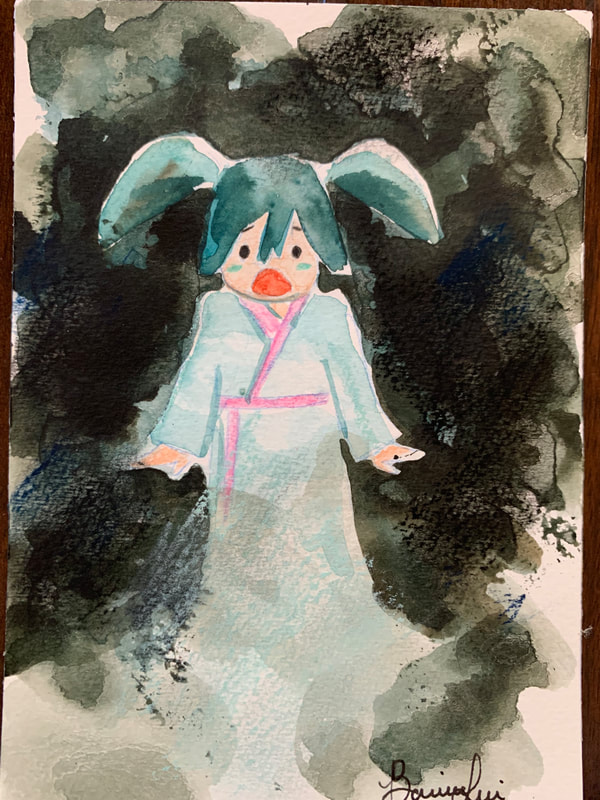

Art for Auction: This 14 x 10 inch watercolor illustration is from Bonnie’s Rocket by Emmeline Lee (2022), a historical fiction picture book inspired by the experiences of the author’s grandfather with the Apollo 11 space mission. It depicts Bonnie, whose father is an engineer for the Apollo 11 space mission, conceptualizing a rocket that she designs, builds and tests.

|

Ellen Heck

|

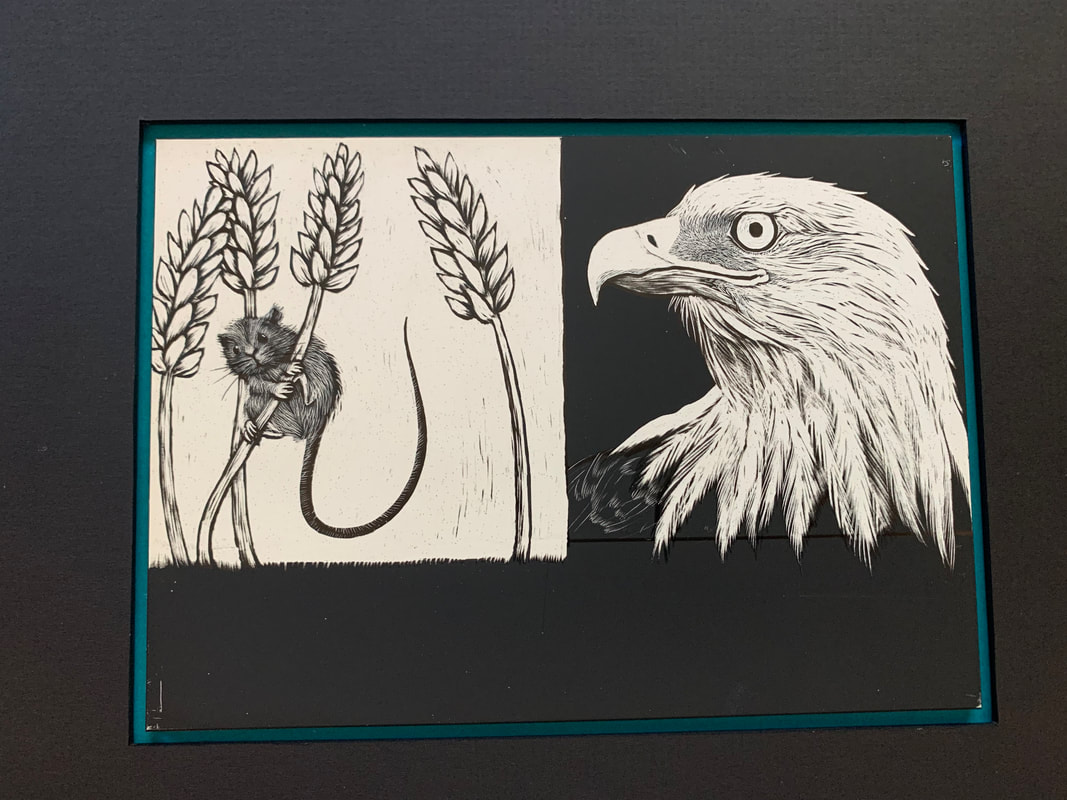

Art for Auction: This 10 x 8 inch piece includes eye-catching black and white scratchboard images from A is for Bee: An Alphabet Book in Translation (2022), her lavishly illustrated debut multilingual alphabet picture book that was inspired by reading Lithuanian alphabet books to her son. Throughout the book, she has included hidden letter forms to create a seek and find element for readers.

|

Kevin Henkes

Bonnie Lui

Juliet Menéndez

|

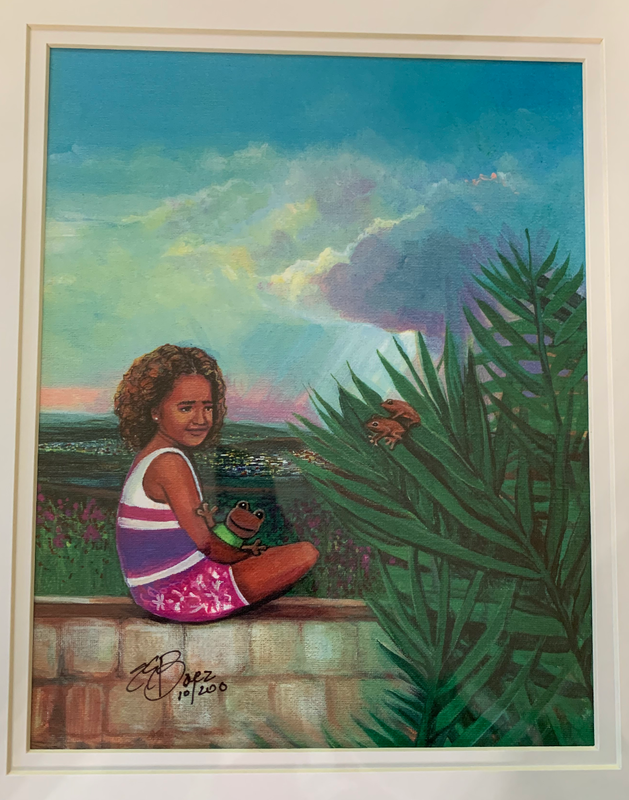

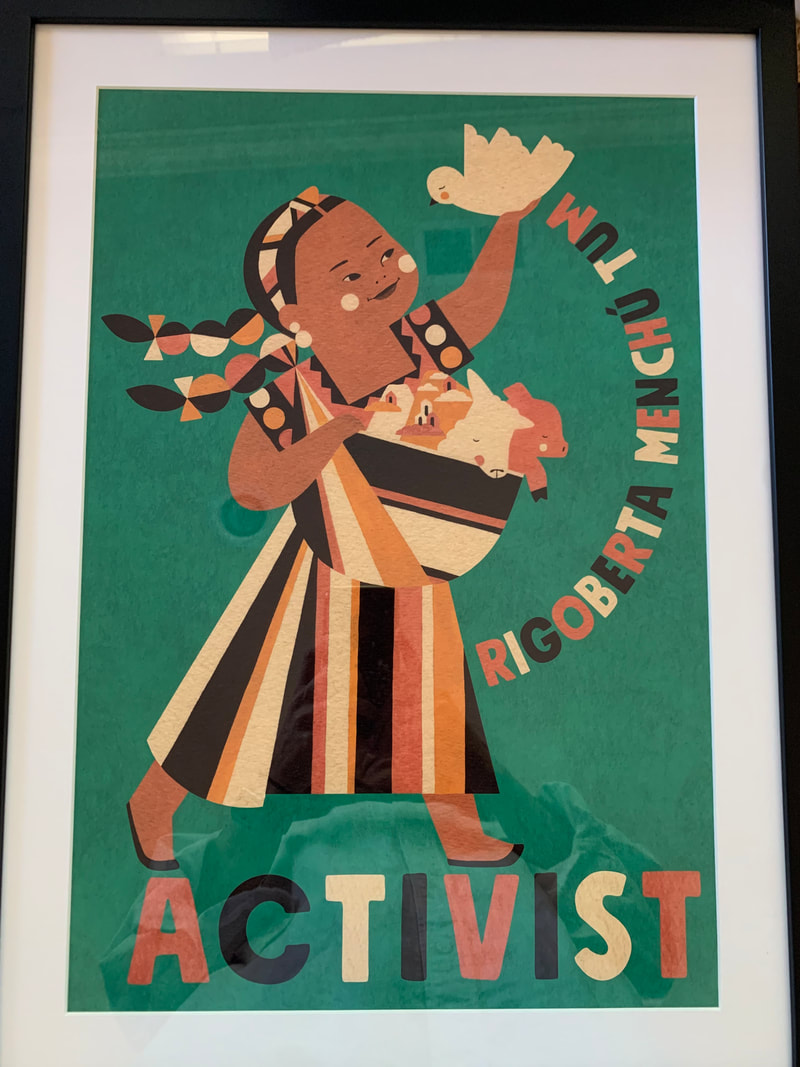

Art for Auction: This framed 18 x 23 inch gorgeous illustration is from Juliet’s first children’s book, Latinitas: Celebrating 40 Big Dreamers (2021), a collected biography of influential Latinas who followed their dreams. It depicts Rigoberta Menchu Tum, the 1992 winner of the Nobel Peace prize, in recognition of her work as an advocate of Indian Rights and ethno-cultural reconciliation. Other Latinas included in the collection include Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor and Evelyn Miralles, NASA’s first virtual reality engineer.

|

Brandon James Scott

Grant Snider

Dan Yaccarino

|

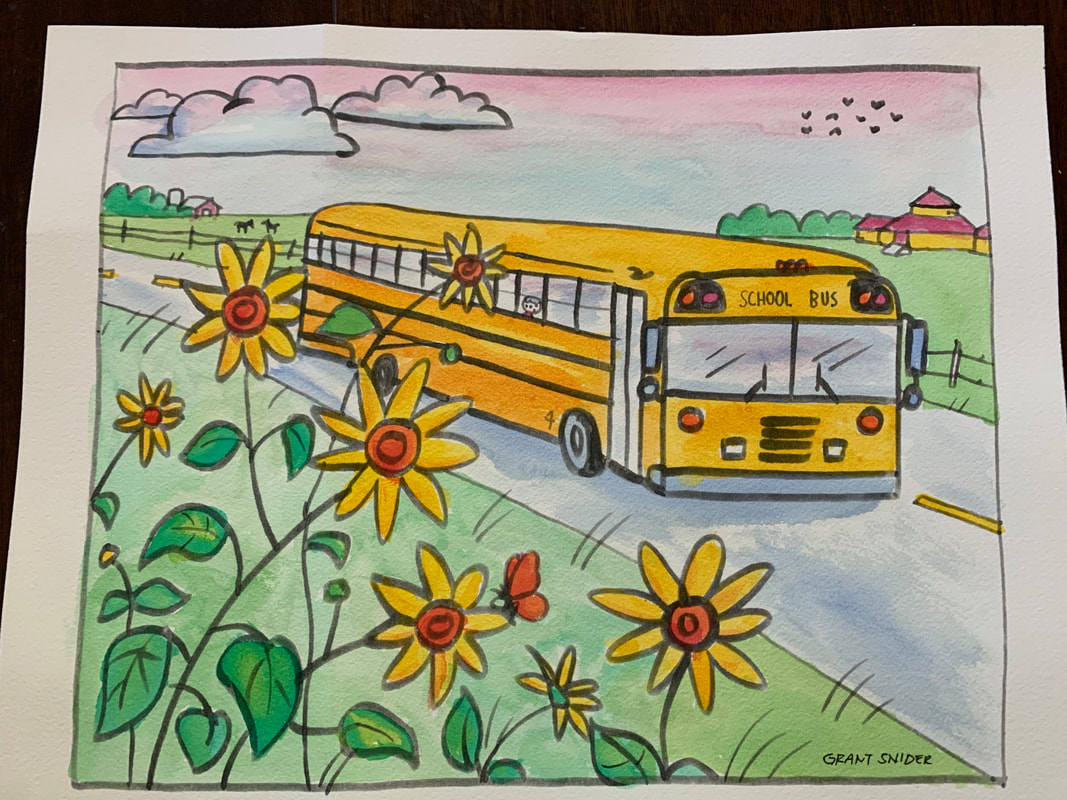

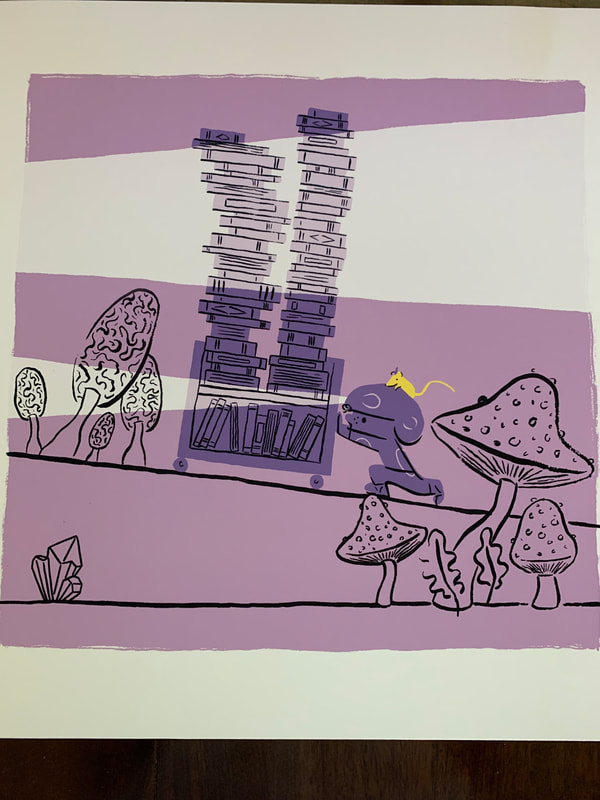

Art for Auction: This 20 x 20 inch graphic style illustration is from City Under the City (2022). It depicts Bix and her rat friend heading home from the City Under the City with books that they have discovered on their adventure. The charming illustrations and Bix’s appreciation for books inspire young readers to move away from a screen and read a book.

|

Ally Hauptman is an associate professor at Lipscomb University. She is the chair of the Ways and Means Committee for CLA and a serving CLA board member.

By Katie Caprino

When I think about the reasons why so many picture books about gardens and nature have sprouted in 2022, I have to think it had something to do with so many of us looking for outlets during times of remote learning and working and a desire to appreciate the beauty of the natural world that comes from the areas of mindfulness and self-care.

But it is important to acknowledge that children’s picture books about gardening and nature are certainly not brand new. Browsing a bookstore recently, I happened upon The Gardener, a 1988 Caldecott Honor Book written by Sarah Stewart and illustrated by David Small. Set in the Depression era, The Gardener tells the story of Lydia Grace, a little girl who goes to live with her uncle for a time. Leaving her grandma and parents behind, Lydia Grace takes seeds to the city, which she uses to grow beautiful planters and rooftop gardens.

Nevertheless, I’m hopeful this blog will help you with your green thumb and, most importantly, give you some teaching ideas for your book garden.

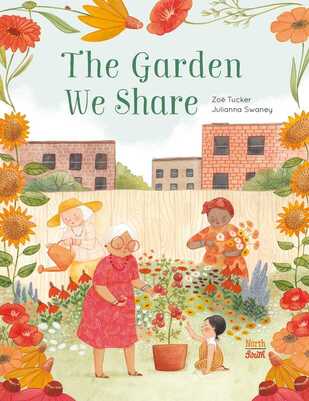

|

Author Zoë Tucker and illustrator Julianna Swaney team up for the 2022 The Garden We Share, a beautiful book about the seasons of a garden - and the seasons of life. A little girl enjoys gardening with an older woman until one day the older woman is no longer there to garden with her. This is a poignant tale that exists on many levels. Whereas some readers will see the story as a story of a garden changing through the season, others will understand the story as a story of the human life cycle. A beautiful story about resilience of the plants to get through the winter and humans to get through the darker times in our lives, The Garden We Share should be on your library shelf. The oversized faces of Swaney’s characters really emphasize the message of connectedness - between people and plants and between people and people - that exists in our world. Use this book in your classroom to inspire students as part of your life cycle units and to encourage students to help others in their community.

|

By Mark I. West

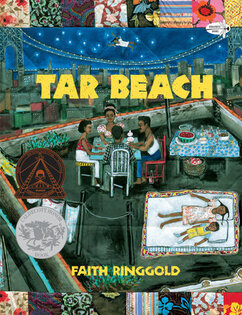

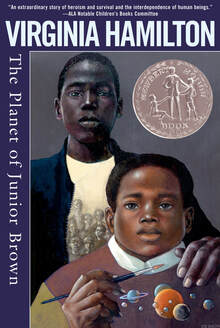

| I recently taught a seminar on urban children’s literature, and I included several books set in Harlem, including Faith Ringgold’s Tar Beach, Virginia Hamilton’s The Planet of Junior Brown, and David Barclay Moore’s The Stars Beneath Our Feet. The central characters in these books spend time in protected spaces where they temporarily escape from reality. I started the discussion of Tar Beach by reading aloud the story of eight-year-old Cassie and her love of spending time on the roof of the building where she lives with her family. The story reminded me of the Motown song “Up on the Roof,” and to my students’ horror, I started singing it. “Up on the Roof” is about escaping the “hustling crowd” by climbing “up to the top of the stairs” and spending time in the “trouble proof” space “up on the roof.” This summary equally applies to Tar Beach, but Ringgold’s story goes beyond the theme of escape. |

Ringgold portrays the rooftop as a liminal space where reality and fantasy merge. In her fantasy flights, Cassie helps her father overcome the racial discrimination that he faces. Within the context of her fantasies, she feels good about herself because she can make life better for her family. Her fantasies correspond to a point that Bruno Bettelheim makes in The Uses of Enchantment about the healing power of fantasy. “While the fantasy is unreal,” Bettelheim writes,” the good feelings it gives us about ourselves and our future are real, and these real good feelings are what we need to sustain us.”

| Virginia Hamilton’s The Planet of Junior Brown grew out of an experience Hamilton had while sitting on a park bench in Harlem. She noticed a homeless boy and wondered about his situation. She imagined that he might have a friend and perhaps a caring adult in his life. Drawing on this experience, she created the novel’s three central characters: Buddy, a homeless boy; Junior Brown, an overweight boy who has a low sense of self-esteem; and Mr. Pool, a former teacher who works as a school janitor. These characters come together in a school basement room that includes a working model of the solar system. Mr. Pool presides over this space and makes it available to the boys. The mechanical solar system in the center of the room takes on special significance when Mr. Pool declares that this version of the solar system includes “a fantastic |

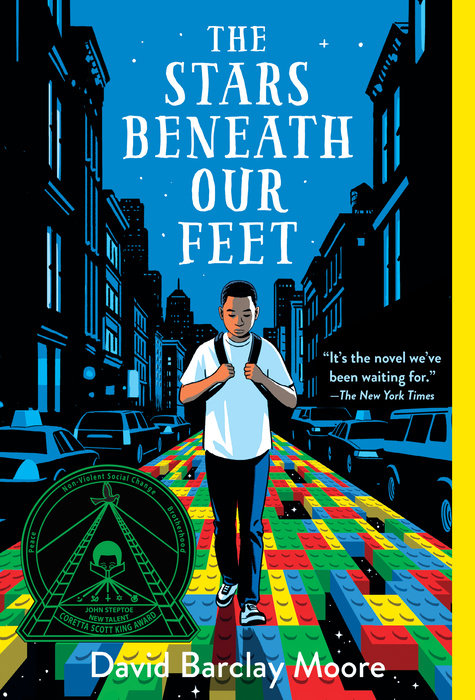

Like Hamilton, David Barclay Moore spent time in Harlem, and he drew on this experience when writing The Stars Beneath Our Feet. Lolly, the central character, is a twelve-year-old boy who lives in contemporary Harlem. His life is upended when his older brother is killed in a gang-related incident. Lolly also faces changes in his family situation. Before the novel’s opening, his parents separated, and his mother’s girlfriend moved into the apartment. Lolly reacts to these events by withdrawing. His depression causes him to lose interest in everything except building with his Legos blocks, an activity he used to do with his brother.

| Lolly comes to the attention of Mr. Ali, a school counselor. Mr. Ali encourages Lolly to talk about his feelings, but Lolly resists. Mr. Ali, however, realizes that Lolly’s passion for Legos might provide Lolly with the key to unlocking his repressed emotions. Mr. Ali repurposes a storage room in the school with the goal of providing Lolly with a place where he can build his Legos creations. One day after school, Mr. Ali leads Lolly to the door of the storage room and tells Lolly, “Your world awaits!” For the first time since his brother’s death, Lolly feels that he has a place where he is in control. He initially uses this space to build his “fantasy fortress,” but he soon starts adding other buildings. For each building, he comes up with an accompanying story. In his words, “I was creating my own new world.” While in this room, Lolly is not just building a community out of Legos blocks; he is rebuilding his sense of self and slowly coming to terms with his emotions related to his brother’s death. |

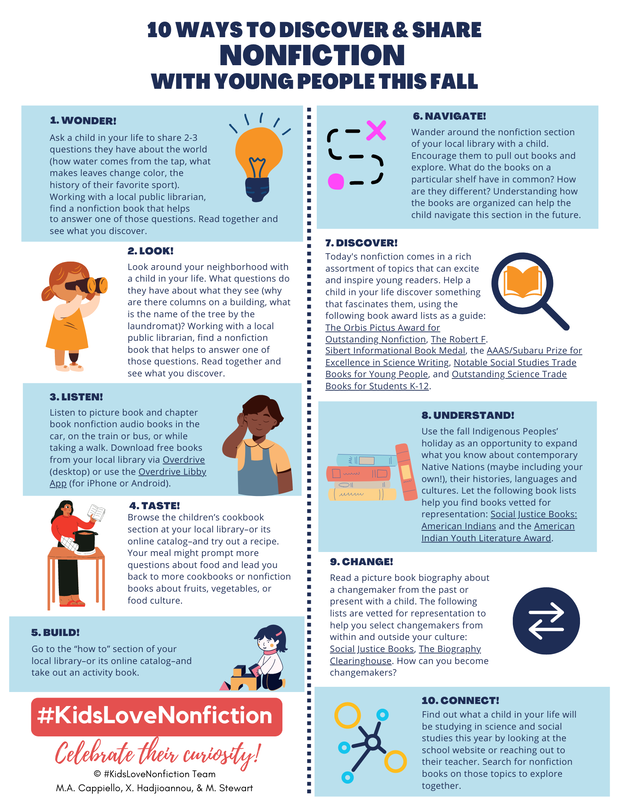

By Mary Ann Cappiello, Xenia Hadjioannou, and Melissa Stewart

As we advocated in our February 14, 2022, letter to The New York Times, #KidsLoveNonfiction! Indeed, several researchers investigating the reading habits and preferences of young children report that, when given the opportunity to self-select, the majority of children enjoy nonfiction as much as or more than fiction (Correia, 2011; Ives et al. 2020; Mohr, 2006; Repaskey et al., 2017). Yet, adults often assume that young people would rather read fiction, and are therefore hesitant to make nonfiction titles available to children or to devote time to exploring nonfiction with the young people in their lives.

- Reading nonfiction = reading.

- Nonfiction affirms young people’s interests.

- Nonfiction deserves to be part of teachers’ considerations as they are setting up their libraries and other classroom spaces.

- Nonfiction books make engaging read alouds.

- Nonfiction books can help diversify the curriculum.

- Nonfiction books can deepen explorations in the science classroom and help children make connections between science and the world around them.

- Nonfiction books can infuse nuance into social studies topics and highlight the contributions and perspectives of historically silenced people.

- Nonfiction books can inspire and support lively book talks and ignite authentic and meaningful inquiry.

Have a wonderful school year!

|

Flyer PDF with clickable links

| |||||||

References

Ives, S. T., Parsons, S. A., Parsons, A. W., Robertson, D. A., Daoud, N., Young, C., & Polk, L. (2020). Elementary Students’ Motivation to Read and Genre Preferences. Reading Psychology, 41(7), 660–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2020.1783143

Mohr, K. A. J. (2006). Children’s Choices for Recreational Reading: A Three-Part Investigation of Selection Preferences, Rationales, and Processes. Journal of Literacy Research, 38(1), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3801_4

Repaskey, L. L., Schumm, J., & Johnson, J. (2017). First and Fourth Grade Boys’ and Girls’ Preferences For and Perceptions About Narrative and Expository Text. Reading Psychology, 38(8), 808–847. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2017.1344165

Xenia Hadjioannou is associate professor of language and literacy education at the Berks campus of Penn State University. She is vice-president of CLA and co-editor of the CLA Blog. She is a founding member of The Biography Clearinghouse.

Melissa Stewart is the award-winning author of more than 200 science-themed nonfiction books for children and co-author of 5 Kinds of Nonfiction: Enriching Reading and Writing Instruction with Children’s Books. Her highly-regarded website features a rich array of nonfiction writing resources.

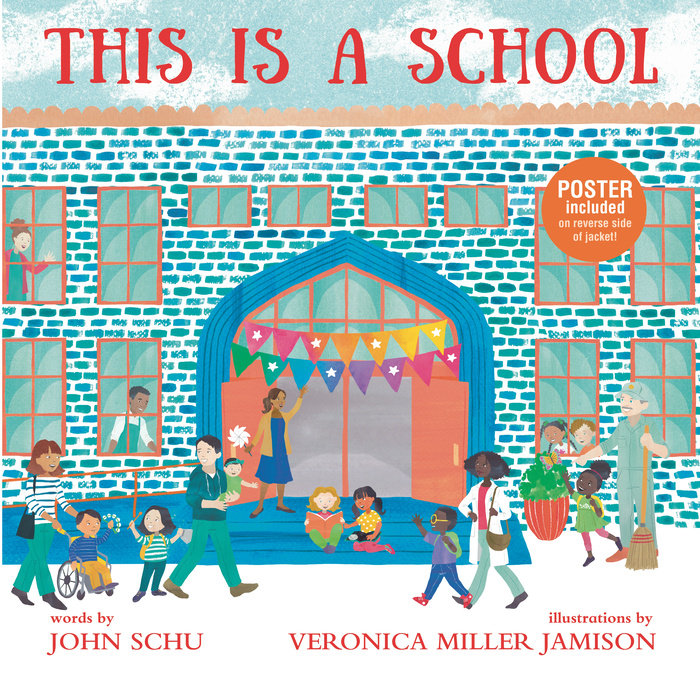

By Susan Polos

There are many more titles not included here, and this is just a sampling, barely scratching the surface of what is available. First day worries are ubiquitous, and books can normalize the sense of unease while bringing classes together to laugh and to consider how creating a sense of belonging for all can set the tone for the whole year.

Authors:

CLA Members

Supporting PreK-12 and university teachers as they share children’s literature with their students in all classroom contexts.

The opinions and ideas posted in the individual entries are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of CLA or the Blog Editors.

Blog Editors

contribute to the blog

If you are a current CLA member and you would like to contribute a post to the CLA Blog, please read the Instructions to Authors and email co-editor Liz Thackeray Nelson with your idea.

Archives

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

October 2023

September 2023

August 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

Categories

All

Activism

Advocacy

African American Literature

Agency

All Grades

American Indian

Antiracism

Art

Asian American

Authors

Award Books

Awards

Back To School

Barbara Kiefer

Biography

Black Culture

Black Freedom Movement

Bonnie Campbell Hill Award

Book Bans

Book Challenges

Book Discussion Guides

Censorship

Chapter Books

Children's Literature

Civil Rights Movement

CLA Auction

CLA Breakfast

CLA Expert Class

Classroom Ideas

Collaboration

Comprehension Strategies

Contemporary Realistic Fiction

COVID

Creativity

Creativity Sponsors

Critical Literacy

Crossover Literature

Cultural Relevance

Culture

Current Events

Digital Literacy

Disciplinary Literacy

Distance Learning

Diverse Books

Diversity

Early Chapter Books

Emergent Bilinguals

Endowment

Family Literacy

First Week Books

First Week Of School

Garden

Global Children’s And Adolescent Literature

Global Children’s And Adolescent Literature

Global Literature

Graduate

Graduate School

Graphic Novel

High School

Historical Fiction

Holocaust

Identity

Illustrators

Indigenous

Indigenous Stories

Innovators

Intercultural Understanding

Intermediate Grades

International Children's Literature

Journal Of Children's Literature

Language Arts

Language Learners

LCBTQ+ Books

Librarians

Literacy Leadership

#MeToo Movement

Middle Grade Literature

Middle Grades

Middle School

Mindfulness

Multiliteracies

Museum

Native Americans

Nature

NCBLA List

NCTE

NCTE 2023

Neurodiversity

Nonfiction Books

Notables

Nurturing Lifelong Readers

Outside

#OwnVoices

Picturebooks

Picture Books

Poetic Picturebooks

Poetry

Preschool

Primary Grades

Primary Sources

Professional Resources

Reading Engagement

Research

Science

Science Fiction

Self-selected Texts

Small Publishers And Imprints

Social Justice

Social Media

Social Studies

Sports Books

STEAM

STEM

Storytelling

Summer Camps

Summer Programs

Teacher

Teaching Reading

Teaching Resources

Teaching Writing

Text Sets

The Arts

Tradition

Translanguaging

Trauma

Tribute

Ukraine

Undergraduate

Using Technology

Verse Novels

Virtual Library

Vivian Yenika-Agbaw Student Conference Grant

Vocabulary

War

#WeNeedDiverseBooks

YA Lit

Young Adult Literature

RSS Feed

RSS Feed