By Mark I. West

Cassie loves being with her family and neighbors on the “tiny rooftop” that she calls her “Tar Beach.” Her parents put a mattress on the roof for Cassie to sleep on while the adults are visiting. For Cassie, “Sleeping on Tar Beach was magical. Lying on the roof in the night, with stars and skyscraper buildings all around me, made me feel rich, like I owned all that I could see.” Cassie fantasizes that she can fly. The illustrations depict her soaring above New York City. Ringgold portrays the rooftop as a liminal space where reality and fantasy merge. In her fantasy flights, Cassie helps her father overcome the racial discrimination that he faces. Within the context of her fantasies, she feels good about herself because she can make life better for her family. Her fantasies correspond to a point that Bruno Bettelheim makes in The Uses of Enchantment about the healing power of fantasy. “While the fantasy is unreal,” Bettelheim writes,” the good feelings it gives us about ourselves and our future are real, and these real good feelings are what we need to sustain us.”

planet known as Junior Brown.” Junior Brown likes the idea of having a planet named after him, and he enjoys creating stories about his planet. For Junior Brown, this experience helps him gain a better sense of self-worth. For Buddy, this room provides him with the sense of security that helps him move beyond being one of the “tough, black children of city streets.” In the process, he begins to imagine a new future for himself. Like Hamilton, David Barclay Moore spent time in Harlem, and he drew on this experience when writing The Stars Beneath Our Feet. Lolly, the central character, is a twelve-year-old boy who lives in contemporary Harlem. His life is upended when his older brother is killed in a gang-related incident. Lolly also faces changes in his family situation. Before the novel’s opening, his parents separated, and his mother’s girlfriend moved into the apartment. Lolly reacts to these events by withdrawing. His depression causes him to lose interest in everything except building with his Legos blocks, an activity he used to do with his brother.

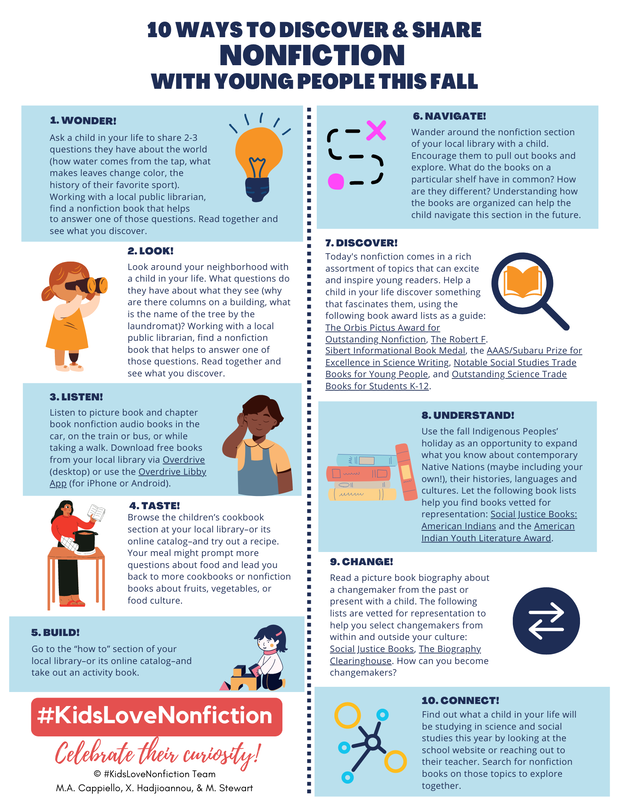

The protagonists in these books all spend time in liminal spaces where the boundaries between reality and fantasy blur. For my students, these books brought back childhood memories of special places where they, too, felt that reality and fantasy merged. For one, it was a treehouse that she and her brother built, taking their inspiration from the Magic Tree House series. For another, it was a walk-in closet where she set up her dollhouse. When I started the class, I had no idea that these books would spark such lively discussions, but I now realize that these books tap into an aspect of childhood that resonates with students from various backgrounds. They might not be familiar with the term “liminal space,” but they all can relate to the quasi-magical experience of being in a liminal space. Mark I. West is a Professor of English at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and a member of CLA. By Mary Ann Cappiello, Xenia Hadjioannou, and Melissa Stewart We are fortunate to be in the midst of a golden age for nonfiction literature for young people. Today’s nonfiction pushes boundaries in form and function, and its creators write about an ever expanding array of topics. In these books, young people encounter well-researched and nuanced explorations of cutting edge scientific discoveries, underexplored moments throughout history and in our current time, compelling accounts of historically marginalized and minoritized communities and perspectives, and more. As we advocated in our February 14, 2022, letter to The New York Times, #KidsLoveNonfiction! Indeed, several researchers investigating the reading habits and preferences of young children report that, when given the opportunity to self-select, the majority of children enjoy nonfiction as much as or more than fiction (Correia, 2011; Ives et al. 2020; Mohr, 2006; Repaskey et al., 2017). Yet, adults often assume that young people would rather read fiction, and are therefore hesitant to make nonfiction titles available to children or to devote time to exploring nonfiction with the young people in their lives. As the school year begins, we want to remind all adults who are involved in the reading lives of children that:

To raise awareness of the potential of nonfiction books to empower young people by feeding their interests and creating pathways to their passions, we’ve created the flyer 10 Ways to Discover & Share Nonfiction with Young People this Fall. We hope it will find its way onto classroom walls, library displays, and home fridges and inspire teachers, librarians, parents, and all people who read with children. Have a wonderful school year!

References Correia, M. P. (2011). Fiction vs. Informational Texts: Which Will Kindergartners Choose? Young Children, 66(6), 100–104. Ives, S. T., Parsons, S. A., Parsons, A. W., Robertson, D. A., Daoud, N., Young, C., & Polk, L. (2020). Elementary Students’ Motivation to Read and Genre Preferences. Reading Psychology, 41(7), 660–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2020.1783143 Mohr, K. A. J. (2006). Children’s Choices for Recreational Reading: A Three-Part Investigation of Selection Preferences, Rationales, and Processes. Journal of Literacy Research, 38(1), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3801_4 Repaskey, L. L., Schumm, J., & Johnson, J. (2017). First and Fourth Grade Boys’ and Girls’ Preferences For and Perceptions About Narrative and Expository Text. Reading Psychology, 38(8), 808–847. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2017.1344165 Mary Ann Cappiello teaches courses in children’s literature and literacy methods at Lesley University, blogs about teaching with children’s literature at The Classroom Bookshelf and Text Sets and Trade Books, and is a founding member of The Biography Clearinghouse. She is a former chair of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8. Xenia Hadjioannou is associate professor of language and literacy education at the Berks campus of Penn State University. She is vice-president of CLA and co-editor of the CLA Blog. She is a founding member of The Biography Clearinghouse. Melissa Stewart is the award-winning author of more than 200 science-themed nonfiction books for children and co-author of 5 Kinds of Nonfiction: Enriching Reading and Writing Instruction with Children’s Books. Her highly-regarded website features a rich array of nonfiction writing resources. |

Authors:

|

||||||||||||||

CLA

About CLA

|

Journal of Children's Literature

Write for JCL

|

ResourcesCLA-sponsored NCTE Position Statements

|

Members-Only Content

CLA Video Library

|

© COPYRIGHT 2018.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed