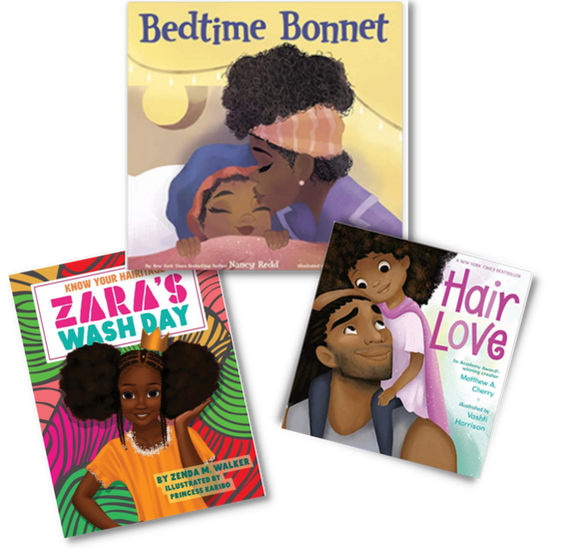

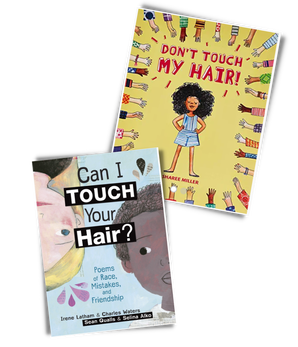

By Tiffeni FontnoHair plays a vital role in a Black person’s identity, especially as Black children grapple with understanding how they belong. Historically, Black hairstyles originating from Africa could identify a region, a person’s age, religion, or status in society, and in some cultures, hair has spiritual connections (Dabiri, 2020). Reintroduced into the conversation through The Crown Act, even in education, Black hair has been policed through discriminatory school codes and policy standards, widening the marginalization against culturally inclusive, responsive, and sustainable identity practices. Black hair has been subjected to colorism, discrimination based on color, and texturism; the belief that certain hair textures are better than others. Based on enslavement and Western standards of beauty, the idea of "good hair," straight more European, and "bad hair," hair that is curlier and kinkier, creates a standard of sociocultural standards that are a source of contention to this very day (Byrd, 2001). Culturally responsive teaching involves incorporating culture, knowledge, language, perspectives, and experiences into the curriculum and instruction for more engaging and meaningful learning experiences (Ladson-Billings, 2009). Educators may not be culturally proficient or prepared through teacher education programs to connect with the nuances of relationship building and teaching diverse student populations (Gay, 2002). In this post, I share books and resources for educators to learn and understand the importance of the representation and appreciation of Black hair for students from kindergarten through-8th grade. History The Story of Afro Hair (Upper-Elementary-High School) Centered from a Black British perspective, Chimbiri’s non-fiction book The Story of Afro Hair sensitively tells a detailed account of the history of Black hair. This stylized journey details hairdos, products, innovations, the science of Black hair, and the philosophy behind styles, like locks. Also included in the back matter are a glossary and additional references. Cornrows (Elementary-Middle School) Cornrows is a fictional story that intertwines and connects the history and pride of Black culture through hair design. Released in 1997, Yarbrough's book, told through the storytelling of Great-Grammaw, inspires pride, hope, and courage. Both books provide an entryway to a discussion on Black hairstyles, through cultural understanding and historical significance. Hair Care

International Books

Boys and Barbershops

ReferencesByrd, & Tharps, Lori L. (2001). Hair story : untangling the roots of Black hair in America (1st ed.). St. Martin's Press. Dabiri. (2020). Twisted : the tangled history of black hair culture (First U.S. edition.). Harper Perennial. Gay, G. (2002). Preparing for Culturally Responsive Teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(2), 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487102053002003 Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African American children (2nd ed..). Jossey-Bass Publishers.

By Jessica WhitelawLast week I was able to visit the long-awaited Faith Ringgold exhibit, American People, at the New Museum in New York. Many know Ringgold from her book Tar Beach, but this retrospective - her first - features Ringgold as artist/organizer/educator and showcases paintings, murals, political posters, sculptures, and story quilts that span the Harlem Renaissance, the Black Arts Movement, critical feminism, and reach into the landscape of contemporary Black artists working today. After years of a relationship with the book version of Tar Beach, it was moving to stand in front of the original story quilt that the book is based on, this intimate everyday object upon which she wrote, painted, and stitched, to push the boundaries of white western art traditions and explore themes of gender, race, class, history, and social transformation.

Below is a protocol adapted from the steps of art criticism that can be used to support students in developing picturebook practices that engage critical literacy and inquiry. It can be used with Tar Beach, whose content is both accessible and complex enough to use with both younger and older readers. But it offers a flexible participation structure that teachers can use with any picturebook that has rich visual/verbal content. Like most protocols, it works best as a flexible tool not a prescriptive device. Picturebook Read Aloud Protocol Adapted from the steps of art criticism, this protocol provides a framework for sharing picturebooks that aims to cultivate a critical practice. It guides the reader through a process of looking closely to notice what they might otherwise overlook and to use what they know about words and pictures to analyze and make sense of what they see. The stages offer a helpful way to support students of any age through a process and unfolding of critical engagement that relies upon attention to specific details in the work to guide thoughtful engagement and response. The protocol is intended as a facilitation guide for teachers. Wording should be adjusted for the audience/age of the reader. LOOK CLOSELY Take inventory. Examine the cover of the book, the dust jacket and the endpapers. Look closely at the typography, the pictures, the words. Describe what you see and notice in detailed, descriptive language. ANALYZE Use what you know about picturebooks and design to analyze the words and the pictures. Look at the colors, the lines, shapes, textures. Try to determine the media the artist used to make the pictures. Examine the style of the language the writer used. Look for patterns, repetition, rhyme. Draw attention to the picturebook as a unique form of the book that relies on the synergy of the words and the pictures by asking how the words and pictures work together: What do the words tell you that the pictures do not? What do the pictures tell you that the words do not? What happens in between the openings? QUESTION Use questions together to probe and deepen. Stop and ask questions about pages that are visually and/or verbally rich or complex. What sense do you make of this page? How do you know that? Why do you think the author or illustrator chose to do it the way they did? What questions does the page raise for you, make you wonder about? CRITIQUE What do you think the author/illustrator is trying to do or say or show in this book? Who do we see in this book? Who is the audience for this book? Who do you think should read it? Whose voice/voices do we hear? Who do we not hear from? What ideas do you have about the topic/topics in the book? What do you think the storyteller in this book believes or thinks or wants us to know? What questions do you have about what the storyteller is saying and showing? What genre/category does the book belong to? What other work has this author and/or illustrator created and how is it similar to or different from this book? RESPOND After having looked closely at the book, what does this text mean to you? What does the story make you wonder about? How could this story mean different things? To you? To different readers? Additional Teaching Resources for Tar Beach Watch Faith Ringgold read Tar Beach Create a paper story quilt Listen to Faith Ringgold’s favorite songs Explore a Faith Ringgold Text Set:

For Older Readers: Watch the Ted Talk by Kimberlé Crenshaw on intersectionality Examine how Tar Beach explores identity and power at several intersections. Examine other artworks of Faith Ringgold such as her For the Women’s House mural at the Brooklyn Museum or her America series of paintings on the artist’s website Read Ringgold’s feminist artist’s statement from her memoir, We Flew Over the Bridge. Look for themes that connect across and examine how the different art forms allow the themes to be explored differently. Read other excerpts from We Flew Over the Bridge: The Memoirs of Faith Ringgold, and examine how ideas from her life take shape in Tar Beach. Consider the different forms of visual and verbal storytelling that she employs in her work and how ideas are conveyed through different modalities in each. Jessica Whitelaw is faculty member at the University of Pennsylvania in the Graduate School of Education and a member of CLA. by Kate Narita, introduction by Melissa Stewart

In February, CLA members Mary Ann Cappiello, Professor of Language and Literacy at Lesley University and Xenia Hadjioannou, Associate Professor of Language and Literacy Education at Penn State University, sent a letter signed by more than 500 educators to The New York Times asking the paper to add children's nonfiction bestseller lists to parallel the current fiction-focused lists.

The letter was also published on more than 20 blogs that serve the children's literature community--including this one—and amplified on social media as part of the #KidsLoveNonfiction campaign. (To date, more than 2,100 people have signed it.) A few weeks later, The New York Times responded, saying it had no current plans to add nonfiction lists at this time. Many people were disappointed by this decision, including fourth-grade teacher and CLA member Kate Narita, who has written the following essay, bravely sharing how the petition changed her thinking. -- Melissa Strewart Shattering My Implicit Bias Against Nonfiction by Kate Narita

Then, in January, my son mentioned a book he had read, Infinite Powers: How Calculus Reveals the Secrets of the Universe by Steven Strogatz. “Oh,” I said. “Sounds interesting. Did you read it for your calculus class?” “Yes,” he said. “And I really enjoyed it.” Did his statement about enjoying a book wake me up to my implicit bias? No. But I did feel a shift inside me. I was pleasantly surprised and excited because I love talking about books. If he had read something and was excited about it, I could read it and discuss it with him, even if he had only read it because it was a class assignment. Here was a way I could deepen my relationship with him as an adult. Even if it was just a one-time occurrence. I asked if I could read the book when he was done, and he brought it home the next time he visited. Fast forward to February break. As my husband and I were packing for a trip to Maui to celebrate our 25th wedding anniversary, he spotted Infinite Powers in the pile of books I was sorting through on our ottoman and picked it up. “What’s this?” he asked. When I explained, he asked if he could take it to Hawaii, and I nodded. I hadn’t read it yet because, to be honest, reading a whole book about calculus felt too daunting. Instead, I packed and read three books from Kate Messner’s History Smashers series and Rukhsanna Guidroz’s Samira Surfs. I also spotted a copy of Kristin Hannah’s Fly Away in our condo. Since I had watched Hannah’s Firefly Lane on Netflix and was listening to The Four Winds on Libby, I couldn’t resist picking up Fly Away, and I devoured it in a day. As my husband and I sat side-by-side reading on the beach, we talked about Infinite Powers. He told me that while he was enjoying the book, the author gave way too much credit to calculus and not nearly enough to physics. He was kind of cranky about it. Actually, he was truly irritated. I was surprised that he was having an emotional response to the book, a nonfiction book. It had stirred up passion inside him, even though it wasn’t a novel. Did his passion wake me up to my implicit bias? Not yet. But I did feel another shift. He was expressing emotion about a book, and I was listening. In the past, it had almost always been me expressing emotion about a novel and him listening.  In our almost thirty-year relationship, I could only think of one other time when he had emoted about a book. It was Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! by Richard Feynman, which I read because he had read it multiple times and was so excited about it. When we got back home, I spotted this petition (which you can still sign) on Twitter. Two professors of literacy, Mary Ann Cappiello and Xenia Hadjioannou, had written a letter asking The New York Times to add three children’s nonfiction bestseller lists—one for picture books, one for middle grade, and one for young adults. I signed it because, of course, I fully supported nonfiction writers and readers! A couple of weeks later, I saw on Facebook that, even though more than 2,000 people had signed the petition, The New York Times had refused to add children’s nonfiction bestseller lists. After a full day of teaching, I was tired, and reading this unfortunate news made me angry. I looked up from my phone. Across the room, my younger son, who was home on spring break, was reading The Elegant Universe: Superstrings, Hidden Dimensions, and the Quest for the Ultimate Theory by Brian Greene for fun because he had liked Infinite Powers so much and wanted to keep reading and learning. Next to him, my husband was reading an article about the Green Bay Packers on the internet.  In that instant, a lightbulb clicked on in my mind, and an awareness of my implicit bias washed over me like a tidal wave. My husband and younger son are readers. They have always been readers. I just didn’t realize it because narratives and fiction aren’t their jam. But give them nonfiction on topics they find fascinating—math, physics, sports—and they’re all in. They’re curious people who read to learn. They want to know about the world, how it works, and their place in it. The decisionmakers at The New York Times seem to have their own implicit bias against children’s nonfiction, and as long as they do not include lists highlighting these books, they’re failing to acknowledge the 42 percent of our youth who crave true texts. They’re also failing to open the eyes of adults who raise those kids, thinking they’re not readers. Maybe we should petition The Wall Street Journal next.

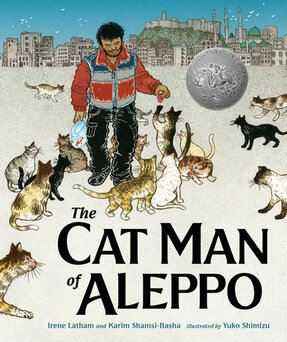

By Amina Chaudhri and Courtney Shimek on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse  The Cat Man of Aleppo is not your typical biography. Its subject, Mohammed Alaa Aljaleel, is an ambulance driver who lives in Aleppo, Syria, where he runs a sanctuary originally established as a cat sanctuary but that has since expanded to include an orphanage. Amid the destruction of the civil war that has been raging for over a decade, Alaa’s sanctuary is a place of peace and hope. This book is a tribute to his work, and a reminder to all of us that we have a responsibility to all living things and that individual acts of compassion can be infectious, leading to collective acts of compassion. Brought to life by Yuko Shimizu’s stunning, intricate illustrations, the city of Aleppo is almost as much a character as the people in The Cat Man. In this month’s Biography Clearinghouse entry, we feature an interview with the book’s creators: Irene Latham, Karim Shamsi-Basha, and Yuko Shimizu. We also explore teaching and learning possibilities that invite readers to learn about the process of research in writing and art, about the effects of war across time and place, and about ways to analyze the illustrations and use them as mentors for new creative projects. Below is an excerpt of the teaching ideas in the Biography Clearinghouse entry for The Cat Man of Aleppo. Researching Visuals In her illustrator’s note, Yuko Shimizu provides readers with a list of references she used to conduct research about the visual images of Syria she created for readers. She spoke of this challenge in her interview with us, and of how this challenge was exacerbated by her being a cultural outsider who had never visited Syria. So much of our research focus with students revolves around writing, but conducting visual research to depict a place as accurately as Yuko did is a challenging skill that requires keen observation skills and strong attention to detail. Begin engaging in this work with students by discussing different elements of visual literacy. As a class, read the first half of Molly Bang’s Picture This: How Pictures Work. Given the visual nature of this book, sharing it using a document camera or leaving it available for students to explore after you read it with them is paramount. Discuss how color, shape, line, scale, texture, motion, etc. change your perception as a reader of visual images. Focus on sections such as the ones on pages 17-19 that depict Little Red Ridinghood as a small red triangle, and how the placement of that triangle on the page shapes how we perceive her vulnerability in the woods. Then select spreads in The Cat Man of Aleppo that similarly make use of composition to evoke our emotions. Some examples include the two-page spread of Alaa and the children surrounded by cats, the spread that follows immediately in which Alaa is surrounded by social media symbols, and the front and back matter spread that depicts a blue sky and white doves.

To see more classroom possibilities and helpful resources connected to The Cat Man of Aleppo, visit the Biography Clearinghouse. Additionally, we’d love to hear how the interview and these ideas inspired you. Email us at [email protected] with your connections, creations, questions, or comment below if you’re reading this on Twitter or Facebook. Amina Chaudhri is an associate professor at Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago, where she teaches courses in children's literature, literacy, and social studies. She is a reviewer for Booklist and a former committee member of NCTE's Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction for Children. Courtney Shimek is a former Preschool teacher and an assistant professor at West Virginia University in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction/Literacy Studies. Her research interests include young readers’ approaches to nonfiction picturebooks, the convergence between literacy and play, and teacher education. |

Authors:

|

CLA

About CLA

|

Journal of Children's Literature

Write for JCL

|

ResourcesCLA-sponsored NCTE Position Statements

|

Members-Only Content

CLA Video Library

|

© COPYRIGHT 2018.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed