By Adam Crawley and Elizabeth Bemiss on behalf of the CLA Diversity, Equity, and Inclusivity CommitteeWe are living and navigating in troubling times. Across the country, educators (e.g., K-12 teachers, librarians, teacher educators, etc.) experience censorship of and challenges to texts that center historically marginalized races, ethnicities, sexual orientations, gender identities and expressions, and other ways of being. In several states (e.g., Florida, Georgia, Utah), legislation explicitly restricts such representations and discussions in K-12+ schools. Simultaneously, cities across the country are supporting newcomers bussed from the U.S.-Mexico border, and schools and libraries specifically are trying to aid these families with daily needs (e.g., food, shelter) and other aspects (e.g., school transitions, providing books in Spanish). Meanwhile, unrest in Africa, the Middle East, and Ukraine continue to weigh heavily on many of our minds and hearts; mass shootings in schools and other public settings remain prevalent; and the upcoming 2024 U.S. Presidential election causes increased tension across politically opposed ideologies. In the midst of all of this, we want to retain hope. We also know that reading and discussing children’s literature with youth can be vital for promoting social justice. To support educators’ on-going work - and in the spirit of Valentine’s Day week - we asked 2023 and 2024 CLA Diversity, Equity, and Inclusivity (DEI) Committee members to share about books they “love” for their representation and ability to foster DEI work. While we recognize that no single book can address all of the world’s current complexities, we hope the recommendations in this list are helpful resources and provide a sense of solidarity for your own contexts.

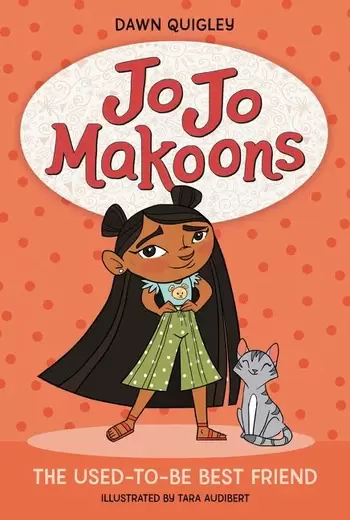

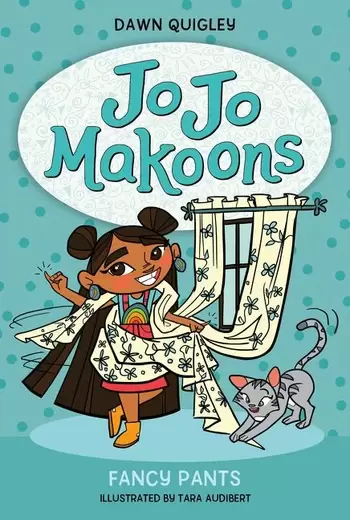

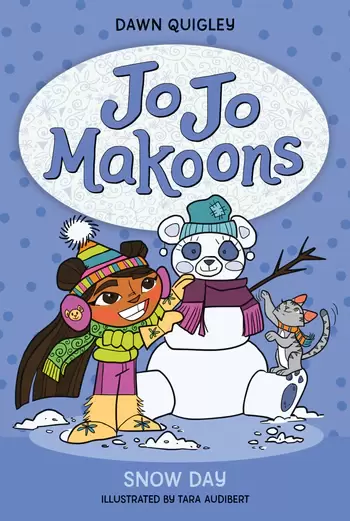

Jo Jo Makoons Series by Dawn Quigley, illustrations by Tara Audibert (Heartdrum) Native Americans have a great love of laughter. In this series, author Dawn Quigley (Turtle Mountain Band of Ojibwe) introduces a spunky seven-year-old named Jo Jo Makoons who lives on an Ojibwe reservation. Jo Jo’s worldview is truly one-of-a-kind as she learns to be friendly, fancy, and imaginative. I love Jo Jo’s hilarious adventures, which are similar to a younger Amelia Bedelia experience. Readers will meet Jo Jo’s Ojibwe family and community (and her pet cat Mimi) as she moves through contemporary, everyday events. Illustrator Tara Audibert (Wolastoqiyik First Nation heritage) adds her comical, cartoon-style artwork to each story in the series. First and second-grade readers will make connections with Jo Jo’s realistic experiences, her feelings in those situations, and learn how she solves her problems. These books are upbeat and humorous, making them a very enjoyable read. (contributor: Andrea M. Page Hunkpapa Lakota)

These poignant and powerful texts that are well loved by CLA DEI committee members illuminate many issues surrounding diversity, equity, and inclusion. These texts speak to issues of race, gender, heritage, and sexual orientation, to name a few, and could be used in the classroom to evaluate the impact of stereotypes or assumptions, to face and dismantle racism, to highlight the value of kindness, or to provide a realistic portrayal of diversity for readers to see themselves and their lived experiences represented in texts. As delineated in the CLA Bylaws, the DEI committee encompasses a steadfast commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusivity within CLA: "The Diversity, Equity, and Inclusivity Committee Chair and members shall help ensure CLA’s commitment to issues of diversity, equity, and inclusivity. The committee shall help create and/or review CLA policies and position statements shared with CLA members and/or the greater public. The committee shall work with membership and nominating committees for recruitment as well as help distribute calls for CLA-related applications. Committee members shall also serve as resources for CLA Standing Committee Chairs when they are developing materials and programs." For more information about the DEI committee, please contact committee chairs Adam Crawley ([email protected]) or Elizabeth Bemiss ([email protected]). Adam Crawley is an Assistant Teaching Professor in the School of Education at the University of Colorado-Boulder. He serves as the 2023 and 2024 CLA DEI Committee chair. Elizabeth Bemiss is an Associate Professor in the School of Education at the University of West Florida. She is a CLA Board Member and chair of the 2023 and 2024 CLA DEI Committee. By Jennifer Slagus and Callie Hammond There is something endlessly energizing about reading new things—whether it’s an anxiously-awaited release, a long-term tenant on your TBR-list, or the research of an emerging scholar (maybe we’re a little biased on that last one). Members of the CLA Student Committee are privileged to do just that: to read exciting books and write about all the exciting ways they can be used in classrooms to improve the lives and learning of our students. Much of our work as early career researchers highlights critical pieces of children’s literature that attend to the social, cultural, and political contexts of our real and literary worlds. We want to share a few recently published, award-winning books relevant to our doctoral research that highlight young peoples’ bravery and acts of resistance. All three are critical, impactful reads worth embedding in each of our classrooms in 2024. Jennifer Slagus I’m a huge fan of books by authors who share a lived reality with their characters. As a neurodivergent researcher, I strive to highlight middle grade novels that help to restory the perceptions of who neurodivergent people are (and who they’re allowed to be). There have been many fabulous authors in the past five years or so who have contributed books that do just that. But one author sticks out to me as an exceptional advocate for neurodivergent acceptance: Sally J. Pla. She’s an autistic middle grade author and the founder of A Novel Mind, a website that centers mental health and neurodiversity representation in children’s fiction. ANM has been a gold mine for my research. Not only does it feature a vibrant blog and a ton of educator resources, but it also has a database of over 1,150 children’s books featuring mental health and neurodiversity representation.

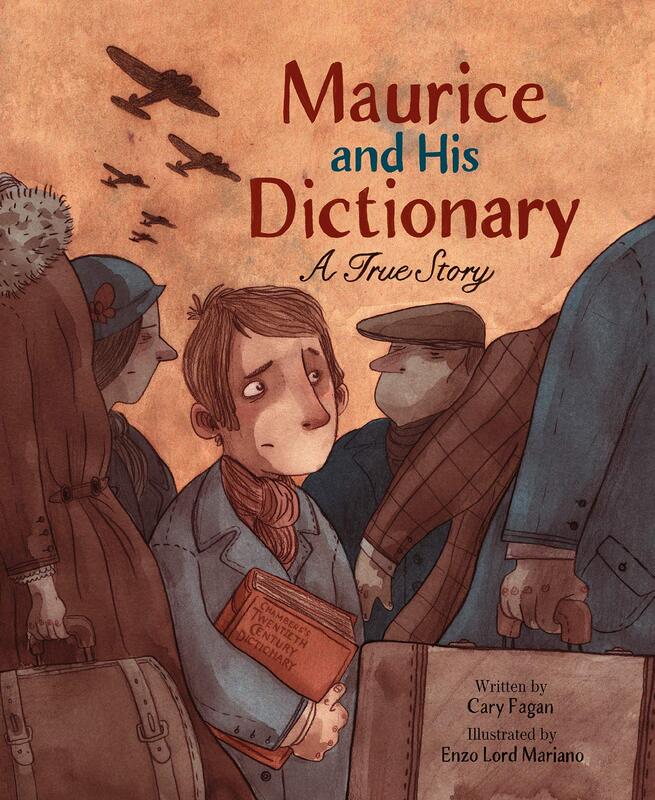

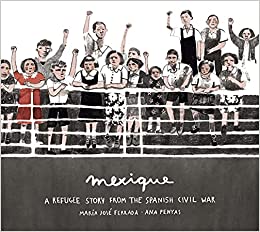

Callie Hammond As a middle school teacher for ten years, I often utilized picturebooks to engage my students and to teach discrete skills, usually about grammar, and to illustrate writing techniques. These lessons had varying success—sometimes the 7th graders would be open to reading a picturebook, other times they rolled their eyes and refused to participate. The most successful picturebooks that I ever brought into my classroom though had nothing to do with grammar or writing, they had to do with Anne Frank. I taught her diary to 6th graders who, unless they were readers themselves and had already discovered World War II fiction, had no knowledge of the Holocaust or how Jews were treated in the years preceding the war. My Anne Frank picturebook collection featured many books about Anne (there are a lot of them out there), but also books that explained significant parts of the war: the night of broken glass, Jewish resistance, children in concentration camps, children who also hid during the war, and many others. Now, as a doctoral student in English education, I have come full circle to analyze the stories of Jewish female protagonists in YA novels about World War II, and representations of the Holocaust in picturebooks. Two of these picturebooks were published in 2023 and feature stories and information that our students need and can learn from. Both books were also just named Notable Books for a Global Society Award for 2024. As is fitting for a book about a traumatic historical event, both are nonfiction and have extensive back matter to explain the stories. Utilizing both of these picturebooks in the classroom with older students can prep them for the heavier history or readings a teacher might soon introduce. They also provide picture evidence of hardships and bravery without being too macabre. Jennifer Slagus is a doctoral candidate at Brock University in Ontario, Canada and Coordinator of Research & Instruction at the University of South Florida Libraries. Jennifer’s doctoral research focuses on representations of neurodivergence in twenty-first century middle grade fiction. Callie Hammond is a doctoral student at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, North Carolina. Callie’s doctoral research focuses on accessing historical knowledge when teaching literature that involves the Holocaust and using critical content analysis to analyze and understand representations of the Holocaust in children’s picturebooks. CLA Student Committee Members

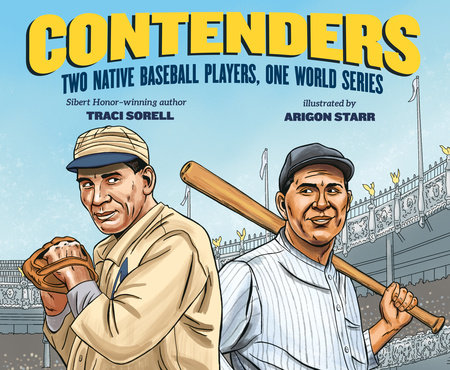

By Andrea M. Page and Jackie Marshall ArnoldWe invite you to the Children's Literature Assembly’s annual event at the 2023 NCTE Convention. Enjoy breakfast with our Keynote Speaker, award-winning author Traci Sorell. The breakfast is Sunday, November 19th, from 7:00am to 8:45am EST in Short North A of the Grand Columbus Convention Center.

If you are a veteran of our CLA Breakfast, you already know what an amazing experience it is! If you have not had the opportunity yet, we invite you to join us for Sunday’s breakfast with an incredible author. Find out what you’ve been missing. The CLA Breakfast is a wonderful opportunity to meet others who are passionate about children’s literature, engage in learning from Traci Sorell, and perhaps go home as a winner of a robust set of award-winning books or an original piece of beautiful art! We hope to see you there! Andrea M. Page (Hunkpapa Lakota) is a board member of the Children’s Literature Assembly and serves as the Co-Chair for the 2023 CLA Breakfast Committee. She is a children’s author, educator and speaker. She lives in Rochester, NY. Jackie Marshall Arnold is a member of the Children’s Literature Assembly and serves as the Co-Chair for the 2023 CLA Breakfast Committee. She is an associate professor at the University of Dayton in Dayton, OH. By Sara K. Sterner, Lisa Pinkerton, and Mary Ann CappielloCLA Expert Class 2023: Nodes of Literary Connection—How Culturally Diverse Imprints are Building Pathways for More Inclusive and Representative Children’s Literature | Saturday, November 18, 2023 from 5:45 PM - 7:00 PM EST (GCCC Room B-130-132)

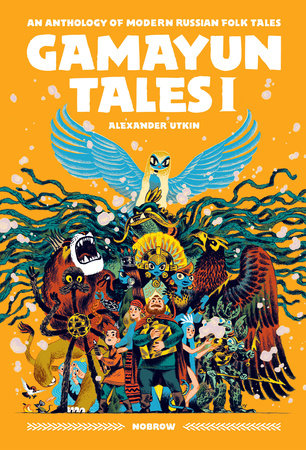

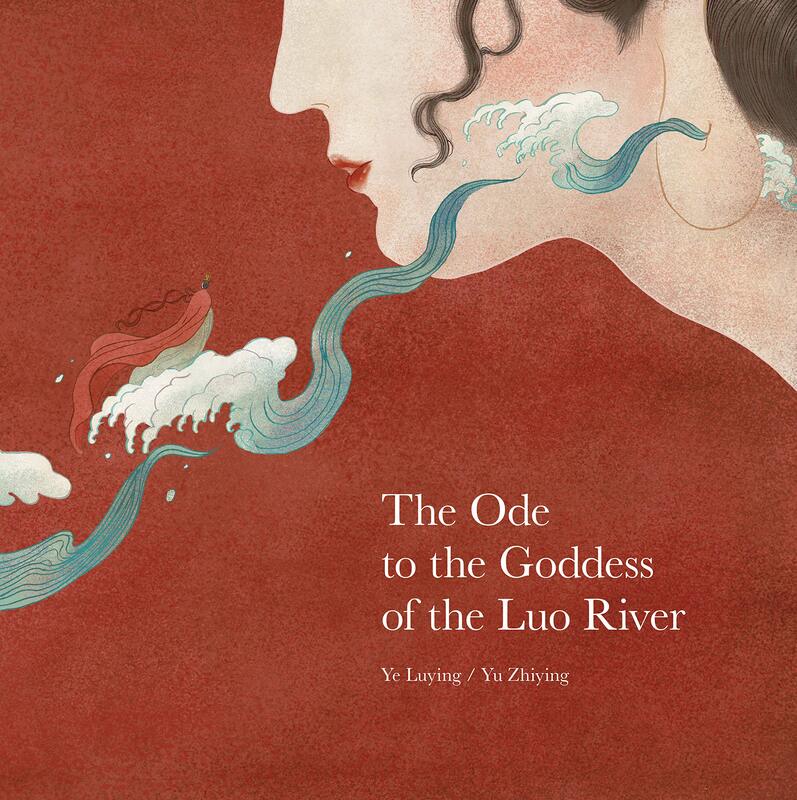

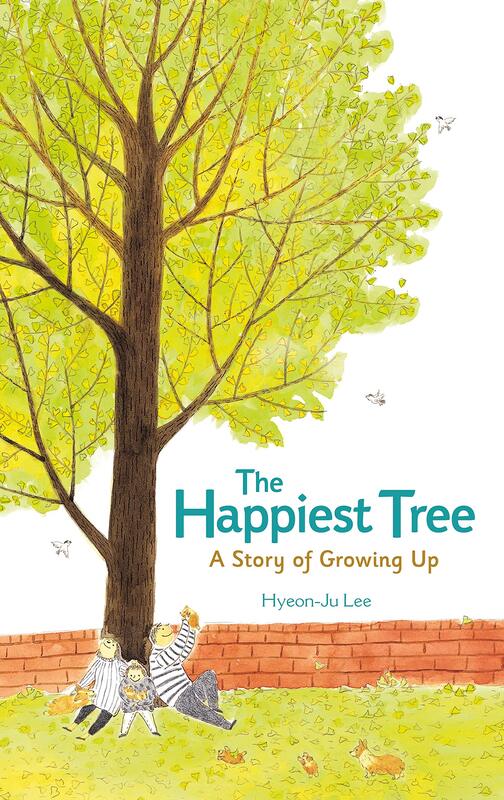

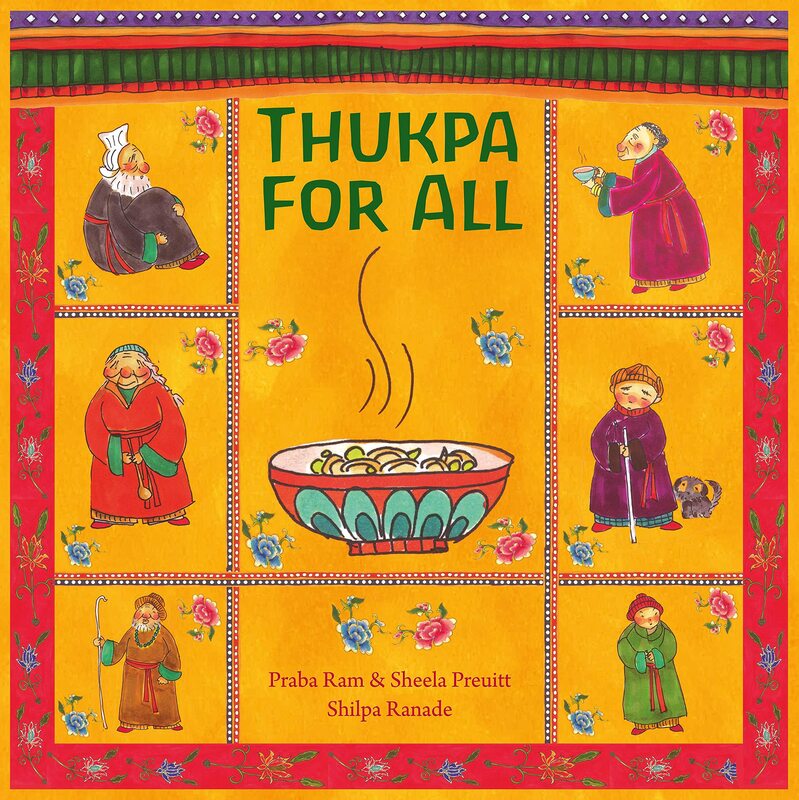

In collaboration with Ellen Myrick, President and Chief Marketer, Publisher Spotlight, the 30th annual Expert Class will feature an impressive gathering of authors, illustrators, publishers, and organizations that are influencing the landscape of inclusive representation in children’s literature for readers and creators alike (Menefee & Johnson, 2021; Rosenberg, 2022). Recognizing a continued dearth of diverse books for young readers, especially those written by diverse creators, the demand for more authentic representation in children’s publishing remains an issue (Menefee & Johnson, 2021). In response, small publishers and imprints are shifting the field—creating extended publishing pathways for inclusive books that serve as authentic nodes of literary connection for young readers. This Expert Class explores a movement in the publishing industry working to expand representation in children's literature that has been woefully lacking in the field. It is our goal that participating in the session will help individuals to build nodes of connection that expand or enhance their knowledge of diverse publishers and creators and the books that they publish. Additionally, participants will have opportunities to discover new books and publishers that center representation and highlight lived experiences that have been historically underrepresented and misrepresented in literature for young people. Importantly, the session has the potential to trailblaze new pathways for participants as they work to guide young readers to experience windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors (Bishop, 1990) that flow out of these literary nodes of connection. This year’s class will provide a unique opportunity for participants to interact directly with publisher/creator teams during the session as they rotate between tables. The session is organized in conversational-style groupings organized around the following focal themes. At each table, speakers will share the focus, vision, and collaborative process that constitute their books and work. In addition to building connections and learning from the experts featured in our Expert Class this year, there will be incredible door prizes and take-aways from the session. Featured Authors

Featured Illustrators

International English Language Books: Featured Publisher

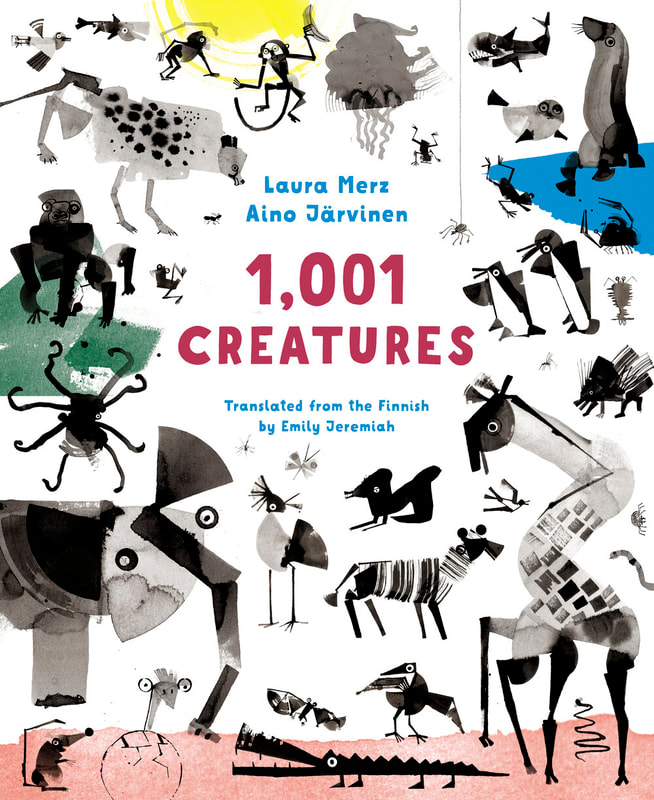

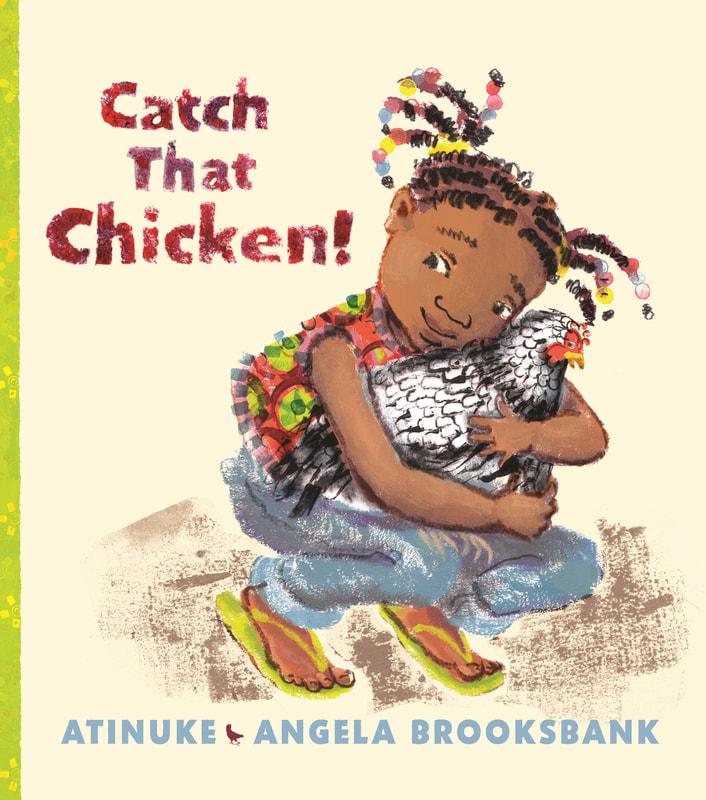

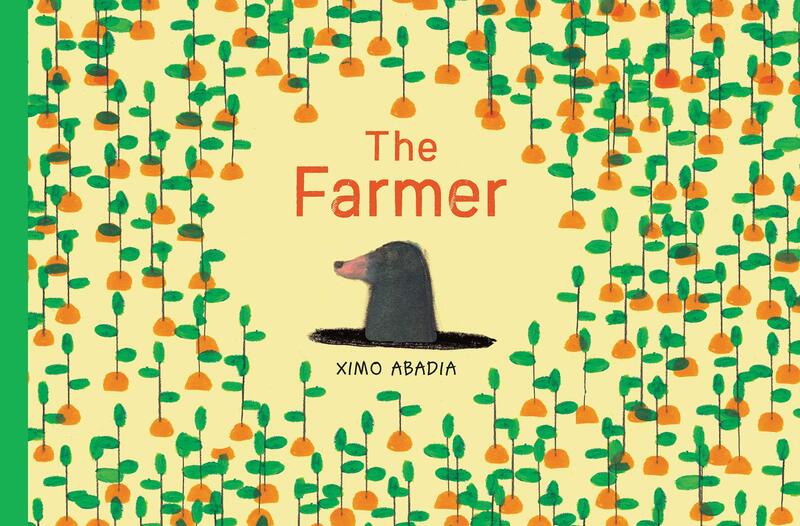

International Translated Books: Featured Publisher

North American Small Presses: Featured Publishers

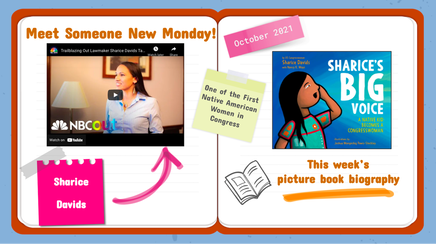

Outstanding International Books/USBBY

References: Bishop, R. S. (1990, Summer). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3). Menefree, D. L. & Johnson, C.F. (2021). Diverse imprints and the classroom: How publishers are taking up the call to package and promote diverse literature for youth. The ALAN Review, 49(1), 85-89. Rosenberg, R. (2022, August 23). Read and learn: Culturally diverse children’s book publishers and imprints. BOOK RIOT. https://bookriot.com/diverse-childrens-book-publishers/ Sara K. Sterner, California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt, CLA Board Member and Expert Class Committee Co-chair Lisa Pinkerton, The Ohio State University, CLA Board Member and Expert Class Committee Co-chair Mary Ann Cappiello, Lesley University, CLA Board Member and Expert Class Committee Co-chair By Mary Ann Cappiello, Jennifer M. Graff and Melissa Quimby on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse  Over the last two years, we’ve enjoyed sharing excerpts from The Biography Clearinghouse website. We hope that our interviews with book creators and our teaching ideas focused on using biographies for a variety of classroom purposes has been helpful to the CLA membership and beyond. This month, we’re very excited to share something different - a voice directly from the classroom. Melissa Quimby, a 4th grade teacher in Massachusetts, has written the inaugural entry in our new feature “Stories from the Classroom.” Melissa is the genius behind #MeetSomeoneNewMonday, a weekly initiative that has spread from her classroom to her grade level team to an entirely different school in just three years. This initiative launched when Melissa decided to share her passion for picturebook biographies with her students through interactive read-alouds. They were hooked! As Melissa writes, “Over time, I molded this project in intentional ways, and it evolved into an adventure that focused on identity, centered marginalized and minoritized communities, and cultivated thoughtful, strategic middle grade readers.” What started as a way to share nonfiction picturebooks as an engaging and compelling art form developed into a more nuanced exploration of global changemakers–past and present. With their weekly reading of picturebook biographies, students grow as readers and thinkers and deepen their individual and collective sense of agency. In the following excerpts, Melissa describes how she reveals each week’s notable changemaker to her students and shares some of her picturebook biography selections. Monday Read-Aloud Routines  Reveal Slide Example Reveal Slide Example On Monday mornings, we gather together as a reading community. In an effort to build excitement, our reveal slide is projected on the board as students arrive. Some weeks, copies of the backmatter wait on the rug, inviting students to preview the figure of the week. This could be the author’s note, a timeline, or a collection of real-life photographs. Once all readers are settled, we watch a video to learn a little bit about the person in the spotlight. Some weeks, interactive read aloud time happens on Monday morning immediately following the reveal. On some Mondays, it works best for us to huddle up in the afternoon. Occasionally, we steal pockets of time throughout our busy schedule to enjoy the biography of the week in smaller doses. When we read the text is not as important as how we read the text. The heart of this work truly lies in how we generate emotional investment within our students and how we help our students’ reactions and ideas blossom into new thinking about the world and ways that they can take action in their own lives for themselves and others. Sometimes, we simply read the biography to love it. In those moments, readers are silent with their eyes glued to the book, scanning the illustrations, wide-eyed when something surprising happens. Perhaps they whisper something to their neighbor, let out an audible gasp or share a comment aloud. Sometimes, we read to grow ideas. In these moments, readers are tracking trouble, considering how the figure responds to obstacles. They are ready to turn to their partner and reach for a precise trait word or theme and supporting evidence. To read more about #MeetSomeoneNewMonday, including Melissa planning process with her grade level team and student responses, visit Stories from the Classroom on The Biography Clearinghouse website You can also reach out to Melissa through her website (QUIMBYnotRamona) or Twitter (@QUIMBYnotRamona) to discuss how to implement #MeetSomeoneNew initiative in your classroom or school. Inspired by Melissa’s picturebook biography initiative or done something similar? Share your ideas and stories with us via email: [email protected]. Or, chime in on Twitter (@teachwithbios), Facebook, or Instagram with your own #teachwithbios ideas and picturebook biography recommendations. Melissa Quimby teaches fourth grade in Massachusetts. She is passionate about helping young writers improve their craft, and her to-be-read list is always stacked with middle grade fiction. Melissa shares her love of children’s literature on Teachers Books Readers and shares about her literacy instruction with the Choice Literacy community. You can connect with her at her website, QUIMBYnotRamona, or follow her on Twitter @QUIMBYnotRamona. Mary Ann Cappiello teaches courses in children’s literature and literacy methods at Lesley University, blogs about teaching with children’s literature at The Classroom Bookshelf. She is a former chair of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8. Jennifer M. Graff is an Associate Professor in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia where her scholarship focuses on diverse children’s literature and early childhood literacy practices. She is a former committee member of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8, and has served in multiple leadership roles throughout her 16+ year CLA membership. By Jessica WhitelawLast week I was able to visit the long-awaited Faith Ringgold exhibit, American People, at the New Museum in New York. Many know Ringgold from her book Tar Beach, but this retrospective - her first - features Ringgold as artist/organizer/educator and showcases paintings, murals, political posters, sculptures, and story quilts that span the Harlem Renaissance, the Black Arts Movement, critical feminism, and reach into the landscape of contemporary Black artists working today. After years of a relationship with the book version of Tar Beach, it was moving to stand in front of the original story quilt that the book is based on, this intimate everyday object upon which she wrote, painted, and stitched, to push the boundaries of white western art traditions and explore themes of gender, race, class, history, and social transformation.

Below is a protocol adapted from the steps of art criticism that can be used to support students in developing picturebook practices that engage critical literacy and inquiry. It can be used with Tar Beach, whose content is both accessible and complex enough to use with both younger and older readers. But it offers a flexible participation structure that teachers can use with any picturebook that has rich visual/verbal content. Like most protocols, it works best as a flexible tool not a prescriptive device. Picturebook Read Aloud Protocol Adapted from the steps of art criticism, this protocol provides a framework for sharing picturebooks that aims to cultivate a critical practice. It guides the reader through a process of looking closely to notice what they might otherwise overlook and to use what they know about words and pictures to analyze and make sense of what they see. The stages offer a helpful way to support students of any age through a process and unfolding of critical engagement that relies upon attention to specific details in the work to guide thoughtful engagement and response. The protocol is intended as a facilitation guide for teachers. Wording should be adjusted for the audience/age of the reader. LOOK CLOSELY Take inventory. Examine the cover of the book, the dust jacket and the endpapers. Look closely at the typography, the pictures, the words. Describe what you see and notice in detailed, descriptive language. ANALYZE Use what you know about picturebooks and design to analyze the words and the pictures. Look at the colors, the lines, shapes, textures. Try to determine the media the artist used to make the pictures. Examine the style of the language the writer used. Look for patterns, repetition, rhyme. Draw attention to the picturebook as a unique form of the book that relies on the synergy of the words and the pictures by asking how the words and pictures work together: What do the words tell you that the pictures do not? What do the pictures tell you that the words do not? What happens in between the openings? QUESTION Use questions together to probe and deepen. Stop and ask questions about pages that are visually and/or verbally rich or complex. What sense do you make of this page? How do you know that? Why do you think the author or illustrator chose to do it the way they did? What questions does the page raise for you, make you wonder about? CRITIQUE What do you think the author/illustrator is trying to do or say or show in this book? Who do we see in this book? Who is the audience for this book? Who do you think should read it? Whose voice/voices do we hear? Who do we not hear from? What ideas do you have about the topic/topics in the book? What do you think the storyteller in this book believes or thinks or wants us to know? What questions do you have about what the storyteller is saying and showing? What genre/category does the book belong to? What other work has this author and/or illustrator created and how is it similar to or different from this book? RESPOND After having looked closely at the book, what does this text mean to you? What does the story make you wonder about? How could this story mean different things? To you? To different readers? Additional Teaching Resources for Tar Beach Watch Faith Ringgold read Tar Beach Create a paper story quilt Listen to Faith Ringgold’s favorite songs Explore a Faith Ringgold Text Set:

For Older Readers: Watch the Ted Talk by Kimberlé Crenshaw on intersectionality Examine how Tar Beach explores identity and power at several intersections. Examine other artworks of Faith Ringgold such as her For the Women’s House mural at the Brooklyn Museum or her America series of paintings on the artist’s website Read Ringgold’s feminist artist’s statement from her memoir, We Flew Over the Bridge. Look for themes that connect across and examine how the different art forms allow the themes to be explored differently. Read other excerpts from We Flew Over the Bridge: The Memoirs of Faith Ringgold, and examine how ideas from her life take shape in Tar Beach. Consider the different forms of visual and verbal storytelling that she employs in her work and how ideas are conveyed through different modalities in each. Jessica Whitelaw is faculty member at the University of Pennsylvania in the Graduate School of Education and a member of CLA. by Rachel Skrlac Lo & Donna Sabis-Burns on behalf of the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee

Institutional Resources to Reject Book ChallengesThis right to access diverse literature and other texts is protected through professional organizations’ mission statements, codes of conduct, and other institutional practices. For example, the National Education Association (NEA) is an example of an institution that can support teachers and school districts responding to these challenges. The NEA, which has 3.2 million members across the nation, believes “every student in America, regardless of family income or place of residence, deserves a quality education” (website), which they support through their mission and actions. Because they are a large and far-reaching organization, their resources act as a standard-bearer, and thus can be used to guide districts' response to book challenges. The NEA’s Code of Ethics, briefly The NEA’s code of ethics is guided by two principles, the first of which is a commitment to the student. It has eight conditions, including that educators have an ethical duty to not: 1. “restrain the student from independent action in the pursuit of learning”, 2. “unreasonably deny the student’s access to varying points of view”, nor 3. “deliberately suppress or distort subject matter”. Additionally, educators must make an effort to: 4. “protect students from harmful conditions”, 5. “not intentionally expose the student to embarrassment or disparagement”, and 6. ensure all students have access to programs, benefits, and advantages regardless of “race, color, creed, sex, national origin, marital status, political or religious beliefs, family, social or cultural background or sexual orientation.” The two remaining conditions are that educators: 7. do not seek private advantage from relationships with students, and 8. will respect students' privacy. Using the Code of Ethics to Respond to Challenges Principle 1 lays out a daunting task for educators: how do we honor the humanity and dignity of all students when some of our beliefs are contradictory? Book challenges highlight this paradox. The adults behind the book challenges argue their children are harmed through the content of these books, and this harm can be manifested as feelings of discomfort, shame and embarrassment, or in exposure to ideas that may lead to “deviance”. According to Principle 1, then, these parents are claiming that being exposed to these books is a harmful condition (condition 4) that results in these children feeling embarrassed and disparaged whether due to sexual content of texts, such as in challenges to George/Melissa, or discovering the longstanding persistent impact of white supremacy, such as in Stamped (condition 5). Yet, if schools were to succumb to these challenges, the result would be changes to curriculum and school resources that would unfairly deny benefits (condition 6) to students who identify differently from the mostly white, mostly straight, mostly Christian, mostly politically conservative, mostly American parents who are leading these challenges. Moreover, by shifting school curriculum and materials based on this loud but small group, schools would further violate the code of ethics by restraining independent action (condition 1), such as access to a diverse and representative library collection. Students would be denied access to multiple points of view (condition 2) by restricting the scope of content and voices. This suppression would distort subject matter (condition 3) and would impede student progress (condition 6). Removing books based on outcry of a small but politically-motivated group violates most of the conditions of commitment to the student in the NEA’s code of ethics. Additionally, because educators must respect students’ privacy (condition 8), educators are guided by an ethical duty to protect students' identities because students warrant this protection of their full humanity. As such, educators must not be compelled to reveal which students need access to these books. We must trust educators when they say there are children who need these books. So, which students need access to these books? All students do. As CLA’s Position Statement on the Importance of Critical Selection and Teaching of Diverse Children’s Literature underscores: Children come to see themselves and their experiences represented in the stories they read and these stories can also provide insight into ways of living and knowing that depart from their own. This point alone makes access to diverse literature an ethical and moral imperative so that all students’ lives and languages are represented, especially those communities whose lives and language have been historically underrepresented in school settings (p. 2). Resisting book challenges, then, is not about supporting or denying an ideological position. It’s affirming our commitment to serve all students. By drawing on a code of ethics, or other institutional materials, educators can respond to these challenges with the support of their profession and an understanding that their desire to serve all students is morally and ethically just. Rachel Skrlac Lo, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor at Villanova University. She is a Board Member (2020-2022) with the Children's Literature Assembly and Co-Chair of the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusivity Committee.

Donna Sabis-Burns, Ph.D., an enrolled citizen of the Upper Mohawk-Turtle Clan, is a Group Leader in the Office of Indian Education at the U.S. Department of Education* in Washington, D.C. She is a Board Member (2020-2022) with the Children's Literature Assembly and Co-Chair of the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusivity Committee. *The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the positions or policies of the U.S. Department of Education. No official endorsement by the U.S. Department of Education of any product, commodity, service, or enterprise mentioned herein is intended or should be inferred. By Bettie Parsons Barger and Jennifer M. GraffFor so many of us, books can feel like best friends, close family members, long-lost relatives, or trusted mentors. We gravitate toward them through our desire to connect or understand, to be inspired, or to experience a new or fresh perspective. As educators and literature advocates we also strive to help youths develop relationships with books, often relying on their curiosity about themselves and the unknown to help forge those connections.The United States Board of Books for Young People’s Outstanding International Books (OIB) lists are excellent resources for such pursuits. Shared in previous CLA Blog posts, each OIB list highlights 40-42 international books that are available in the United States. In 2021, the OIB committee read over 530 books prior to selecting the 42 titles for the 2022 list. These titles represent outstanding literature from 24 different countries and 2 indigenous territories in Canada.

As we look at the past three years of OIB lists, we recognize how our current realities are reflected in the committees’ selections. Julie Flett’s (2021) We All Play/ Kimêtawânaw illustrates humans’ innate connection to nature and the joyous experiences of playing outdoors, as the current pandemic has encouraged. The Elevator (Frankel, 2020) speaks to the power of humorous storytelling to unite strangers who unexpectedly find themselves in close quarters. The current Ukrainian-Russian tensions mirror the conflict in How War Changed Rondo (2021). Silvia Vecchini’s (2019) graphic novel, The Red Zone: An Earthquake Story, and Heather Smith’s (2019) picturebook, The Phone Booth in Mr. Hirota’s Garden, are stirring testimonies about ongoing global natural disasters, such as the recent volcano eruption and subsequent earthquake and tsunami that have devastated the Pacific nation of Tonga. Partnering the beliefs that books including hostile and traumatic events “can provoke reflection and inspire dialogue that sensitizes readers . . .” (Raabe, 2016, p.58) and that “stories are important bridging stones; they can bring people closer together, connect them, and help overcome alienation” (Raabe & von Merveldt, 2018, p.64), we created a sampling of five text sets that can be readily used in K-12 classrooms. A Sampling of Outstanding International Books Text Sets (2020-2022)

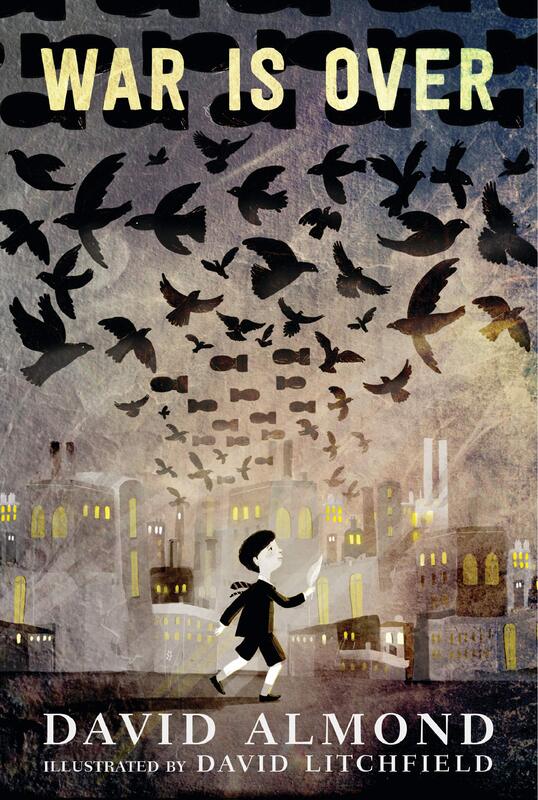

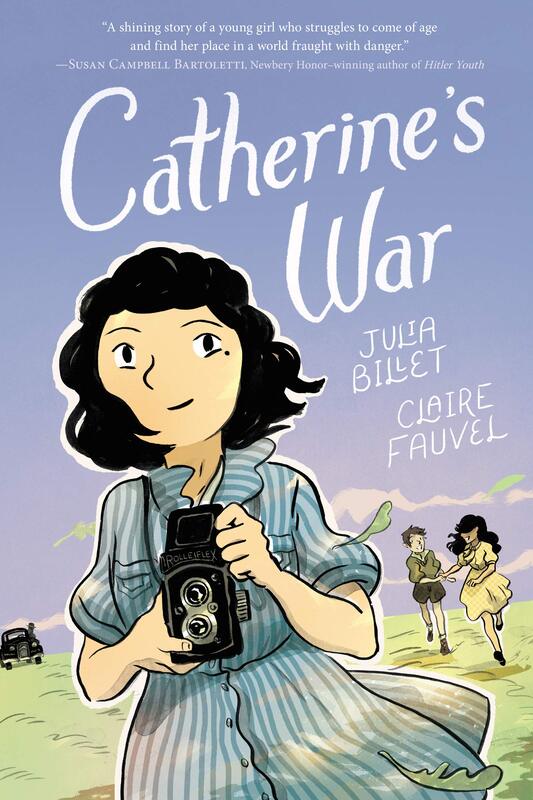

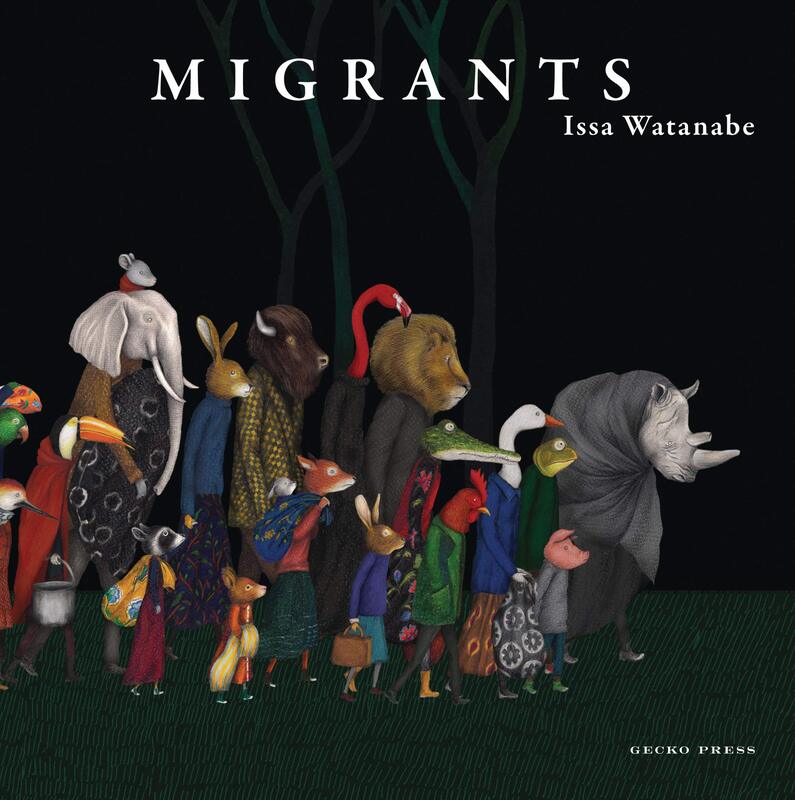

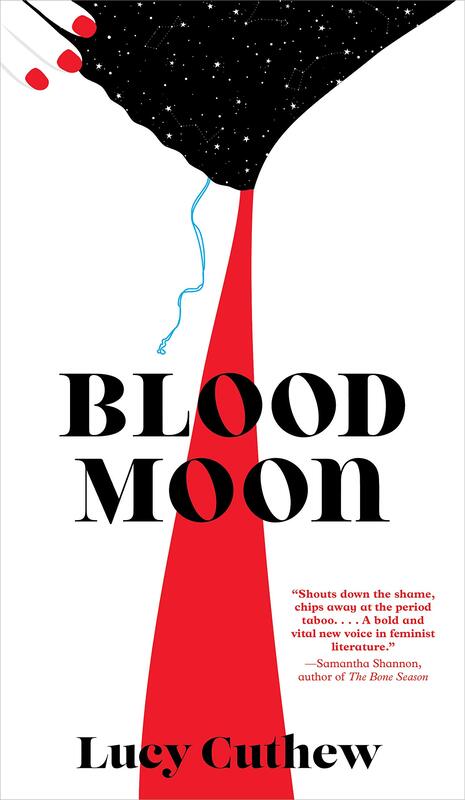

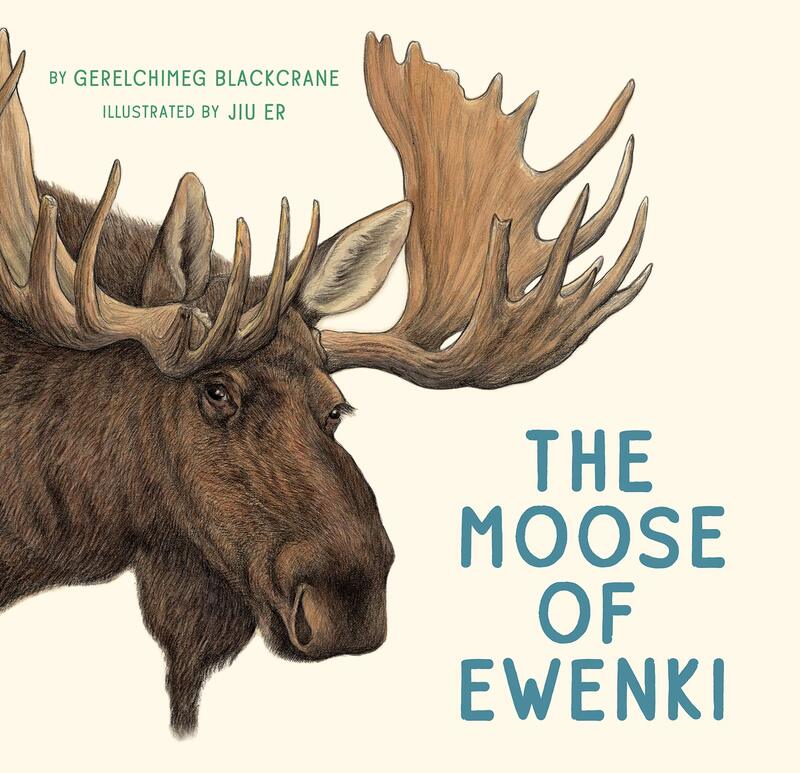

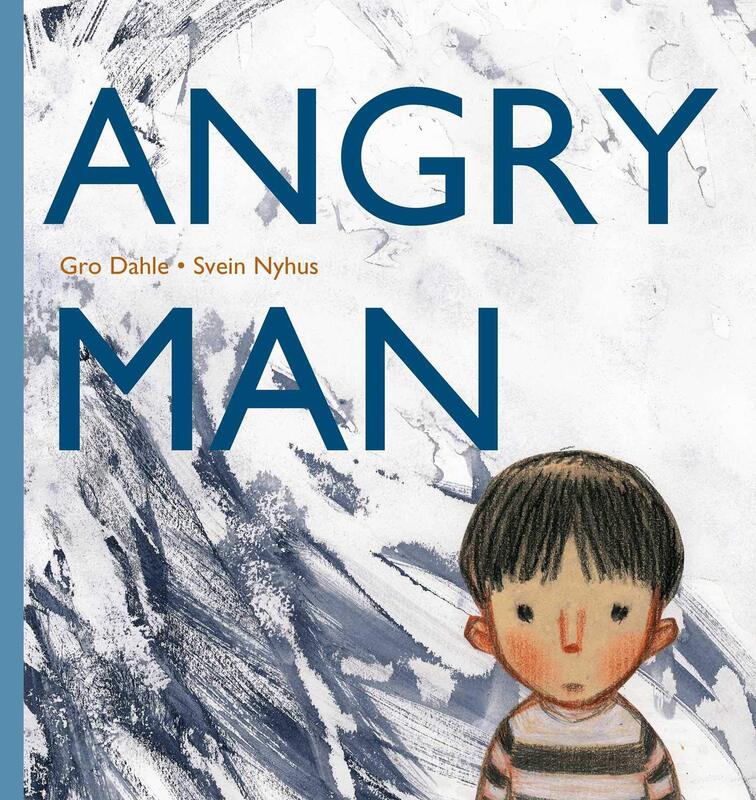

(Book covers are organized by younger-to-older audience gradation.) Wars and Revolutions

(civil, border, global, & cultural) Human Resilience

(civil, border, global, & cultural) Telling Stories and Sharing Memories

(personal, biographical, cultural, geographical, historical, traditional, philosophical, intergenerational, visual, epistolary) Connecting with Nature

(accentuating humans’ relationships with the natural world) Creative Outlets

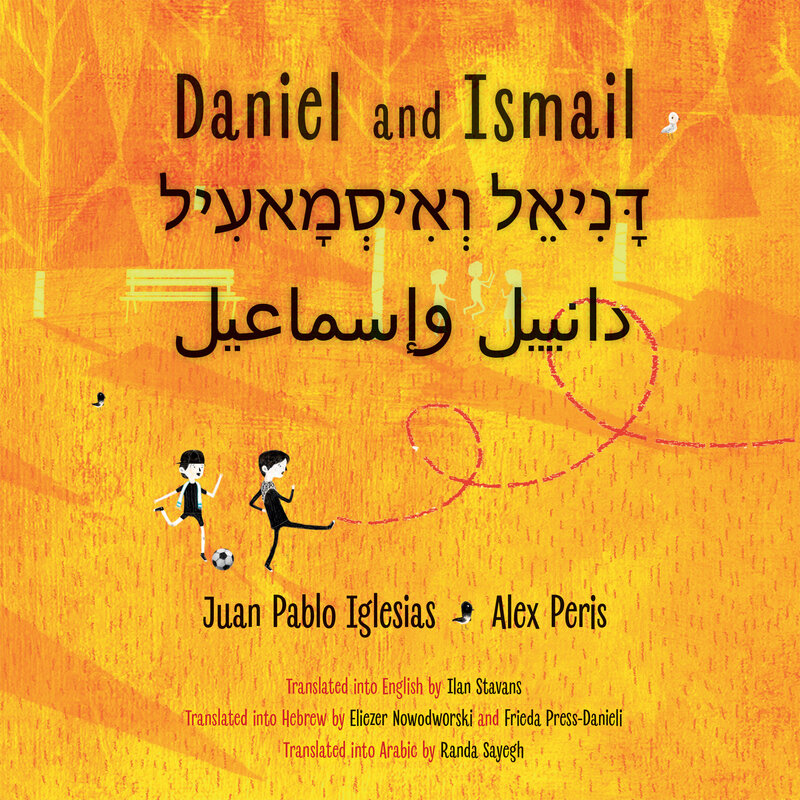

(Playful approaches to familiar topics, how play and curiosity can foster connections and community, and the role of imagination in creating new possibilities and realities, benefits of unexpected journeys)

Featuring over 100 OIB books from the 2020-2022 lists, including all of the 2022 books, these text sets are intentionally broad in scope and varied in format to enable numerous groupings or pairings. Here are a couple of possible groupings. Creative Outlets

Wars and Revolutions

We hope these possible text sets and sub-groupings serve as a springboard for additional text sets that center international stories in our academic and personal lives and help us not only better understand the past but also negotiate the present to help build a more informed, inclusive, and joyous future. For more information about OIB books and USBBY, please join us in Nashville, Tennessee, March 4-6, 2022 for USBBY’s Regional Conference. References Rabbe, C. (2016). “Hello, dear enemy! Picture books for peace and humanity.” Bookbird: A Journal of Children’s LIterature, 54(4), 57-61. Rabbe, C. & von Merveldt, N. (2018). “Welcome to the new home country Germany: Intercultural projects of the International Youth Library with refugee children and young adults.” Bookbird: A Journal of Children’s LIterature, 56(3), 61-65. Bettie Parsons Barger is an Associate Professor in the Department of Education Core at Winthrop University and has been a CLA Member for 10+ years. Jennifer M. Graff is an Associate Professor in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia, is a former CLA President and Member for 15+ years. By Joanne YiAt the tail end of 2020, I completed my dissertation, a large-scale study of Asian American children’s literature. In total, I immersed myself in over 350 Asian American picturebooks, published across the last 25 years. This number surprises many, in part, because it is admittedly a large number to study, but also because few Asian American, bicultural stories are popularly known beyond perennial classroom favorites such as The Name Jar (Choi, 2001) and My Name is Yoon (Recorvits, 2003). Below, I share an adapted excerpt of this work and suggest titles for teachers, librarians, and parents to read and learn about beautiful and resilient Asian American identities and experiences: The last few years have brought to light the increasing importance of the #OwnVoices movement in publishing, which highlights and buoys stories that authentically reflect their authors. In my analysis of Asian American picturebooks, it was evident the stories written by Asian American authors were often tomes of lived experience. They included family histories in prison camps, refugee journeys, memories of grandparents, difficult immigration experiences, and much more. As I read Love As Strong As Ginger (Look, 1999), Hannah is My Name (Yang, 2004), A Different Pond (Phi, 2017), and Drawn Together (Le, 2017), I felt pangs of recognition as I recalled my childhood. These picturebooks were Asian American counterstories (Delgado, 1989), narratives that were different in content, perspective, and ideology from those reflecting the mainstream. The latter often racializes Asian American characters, stereotyping them as a monolith, as perpetual foreigners, and as model minorities. In contrast, the power of counterstories is, as Couzelis (2014) wrote, their “potential to destabilize dominant national myths that act as ‘universal’ histories” (p. 16). It is important to realize that many of these stories were intentionally created to provide Asian American representation. Many stories were inspired by the authors’ own childhoods in the United States and were often tied to specific memories, such as playing with cousins while the adults played mahjong or fishing for that evening’s supper, rather than general experiences, such as moving or acclimating to a new school. Several of the texts that disrupted stereotypical tropes did so because the illustrators figuratively drew themselves into stories not originally written with Asian American characters in mind. It’s no small matter that illustrator Louie Chin depicted Asian American siblings in a silly story about dinosaurs crashing a birthday party (Don’t Ask a Dinosaur, 2018), for example, or that Yumi Heo perceived Bombaloo, an imagined manifestation of anger and petulance, as a little Korean American girl (Sometimes I’m Bombaloo, 2002). These stories are meaningful, not because the starring role in a “White” story was filled by an Asian American, but because the stories finally aligned with the imaginations and realities of Asian American children themselves. The difference lies in stories from Asian Americans and storying about Asian Americans. Myths of the model minority are laid bare with authors’ own stories and family histories of poverty, post-immigration traumas, language barriers, and cultural clashes. They are in stark contrast to those more commonly heard tales of joyous overseas adoptions, racially ambiguous people, fearsome ninjas, and fragile origami, and the myths that come with them. Such stories do not produce connections or reflections for readers. Rather, the defining characteristic of the most notable picturebooks was their commitment to authenticity and the telling of lived experiences. Recommendations for Picture Books I encourage educators and families to explore the diverse richness of Asian America and share these stories with the children in their care.

Dissertation excerpt adapted from Yi, J. H. (2020). Representations, Racialization, and Resistance: Exploring Asian American Picturebooks, 1993–2018 (Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University). References Couzelis, M .J. (2014). Counter-storytelling and ethnicity in twenty-first-century American adolescent historical fiction (UMI No. 3620806) [Doctoral Dissertation, Texas A&M University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. Delgado, R. (1989). Storytelling for oppositionists and others: A plea for narrative. Michigan Law Review, 87(8), 2411–2441. Joanne Yi earned her PhD in Literacy, Culture, and Language Education from Indiana University. A proud MotherScholar and former elementary teacher from Philadelphia, her research interests include critical literacies, textual analysis of diverse children’s literature, issues of inclusion and belonging in elementary and early childhood contexts, and reading education. By S. Adam Crawley, Craig A. Young, and Lisa Patrick on behalf of the CLA Master Class Committee

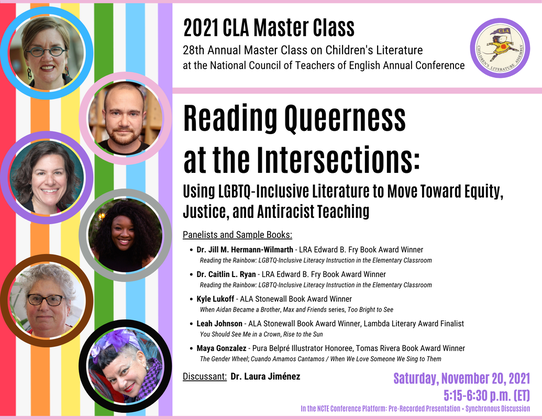

Starting in 1994, the Children's Literature Assembly (CLA) has sponsored a Master Class at the annual NCTE Convention. This session provides K-12 teachers and teacher educators, as well as other members of the organization, the opportunity to gain insight about the use of diverse children's literature through interactions with leading scholars, authors, and illustrators in the field.

The 28th annual Master Class is titled “Reading Queerness at the Intersections: Using LGBTQ-Inclusive Literature to Move Toward Equity, Justice, and Antiracist Teaching.” This year’s session will take place on Saturday, November 20th from 5:15-6:30 p.m. (Eastern) in the virtual platform of NCTE’s annual meeting (1). The 2021 Master Class will include a presentation, panel, and discussion with the following esteemed teacher-educators, authors, and illustrators of children’s literature: 2021 CLA Master Class Contributors

Dr. Laura Jiménez will be the discussant for the 2021 Master Class. Jiménez is a Lecturer of children’s and YA literature courses and Associate Dean for Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion in the Wheelock College of Education and Human Development at Boston University. In addition to her scholarship in The Reading Teacher, Journal of Literacy Research, Journal of Lesbian Studies, and Teaching and Teacher Education among other outlets, Jiménez is a founding advisory board member of the open-access journal Research on Diversity in Youth Literature and the author of the blog “Booktoss” in which she writes critical response to children’s and young adult literature. This year, Jiménez was awarded the Divergent Award for Excellence in Literacy Advocacy given by the Initiative for Literacy in a Digital Age.

The 2021 Master Class

The 2021 Master Class will focus on how children's literature can provide vital depictions of – and be used to facilitate important conversations about - intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1991), specifically where race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and/or gender expression and identity meet and further marginalize. In this session, we bring together scholars, authors, and illustrators of books for young readers whose knowledge, experiences, and published works provide avenues for considering literature’s nuanced portrayal of individuals’ myriad identities. Moreover, both in viewing the presentation and participating in the synchronous dialogue, attendees will have the opportunity to engage in and reflect on conversations that allow them to create paths toward equity, justice, and antiracist teaching in their professional lives.

Participating in the 2021 Master Class will help attendees gauge their knowledge of and comfort with using LGBTQ-inclusive literature in classrooms. Additionally, attendees will learn about the affordances of children's literature that presents stories showing the intersections of diverse identities, especially the voices of individuals whose race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and/or gender identity or expression has been – and continues to be – used to censor or erase them. The Master Class speakers and co-chairs hope attendees leave the session with a reaffirmed and deeper understanding 1) of the need for inclusive representations of marginalized communities and 2) that any move toward equity, justice, and antiracist teaching requires being more inclusive of - and attentive to - intersectional identities.

References:

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299.

(1) The 2021 Master Class is designated by NCTE to be a “pre-recorded/scheduled” format. The recording will be shown in the conference platform at the scheduled time. Following the recording, there will be opportunities for live discussion between presenters and attendees.

S. Adam Crawley (he/him) is an Assistant Professor of Language and Literacy Studies at The University of Texas at Austin. His current roles with CLA include serving as a Board Member (2021-2023) and Master Class Co-Chair (2020-2022). In addition, he is the secretary of NCTE’s Genders and Sexualities Equalities Alliance (GSEA).

Craig A. Young (he/him) is a Professor of Teaching & Learning at Bloomsburg University of PA. He is currently serving on the CLA Diversity, Equity, and Inclusivity Committee, as well as co-chairing the 2021 CLA Master Class. Lisa Patrick (she/her) is the Marie Clay Endowed Chair in Reading Recovery and Early Literacy at The Ohio State University. She is a CLA Board Member and Master Class Co-Chair.

FOR CLA MEMBERS

CLA Board of Directors Elections

|

Authors:

|

CLA

About CLA

|

Journal of Children's Literature

Write for JCL

|

ResourcesCLA-sponsored NCTE Position Statements

|

Members-Only Content

CLA Video Library

|

© COPYRIGHT 2018.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed