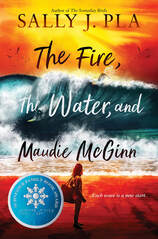

By Jennifer Slagus and Callie Hammond There is something endlessly energizing about reading new things—whether it’s an anxiously-awaited release, a long-term tenant on your TBR-list, or the research of an emerging scholar (maybe we’re a little biased on that last one). Members of the CLA Student Committee are privileged to do just that: to read exciting books and write about all the exciting ways they can be used in classrooms to improve the lives and learning of our students. Much of our work as early career researchers highlights critical pieces of children’s literature that attend to the social, cultural, and political contexts of our real and literary worlds. We want to share a few recently published, award-winning books relevant to our doctoral research that highlight young peoples’ bravery and acts of resistance. All three are critical, impactful reads worth embedding in each of our classrooms in 2024. Jennifer Slagus I’m a huge fan of books by authors who share a lived reality with their characters. As a neurodivergent researcher, I strive to highlight middle grade novels that help to restory the perceptions of who neurodivergent people are (and who they’re allowed to be). There have been many fabulous authors in the past five years or so who have contributed books that do just that. But one author sticks out to me as an exceptional advocate for neurodivergent acceptance: Sally J. Pla. She’s an autistic middle grade author and the founder of A Novel Mind, a website that centers mental health and neurodiversity representation in children’s fiction. ANM has been a gold mine for my research. Not only does it feature a vibrant blog and a ton of educator resources, but it also has a database of over 1,150 children’s books featuring mental health and neurodiversity representation.

Callie Hammond As a middle school teacher for ten years, I often utilized picturebooks to engage my students and to teach discrete skills, usually about grammar, and to illustrate writing techniques. These lessons had varying success—sometimes the 7th graders would be open to reading a picturebook, other times they rolled their eyes and refused to participate. The most successful picturebooks that I ever brought into my classroom though had nothing to do with grammar or writing, they had to do with Anne Frank. I taught her diary to 6th graders who, unless they were readers themselves and had already discovered World War II fiction, had no knowledge of the Holocaust or how Jews were treated in the years preceding the war. My Anne Frank picturebook collection featured many books about Anne (there are a lot of them out there), but also books that explained significant parts of the war: the night of broken glass, Jewish resistance, children in concentration camps, children who also hid during the war, and many others. Now, as a doctoral student in English education, I have come full circle to analyze the stories of Jewish female protagonists in YA novels about World War II, and representations of the Holocaust in picturebooks. Two of these picturebooks were published in 2023 and feature stories and information that our students need and can learn from. Both books were also just named Notable Books for a Global Society Award for 2024. As is fitting for a book about a traumatic historical event, both are nonfiction and have extensive back matter to explain the stories. Utilizing both of these picturebooks in the classroom with older students can prep them for the heavier history or readings a teacher might soon introduce. They also provide picture evidence of hardships and bravery without being too macabre. Jennifer Slagus is a doctoral candidate at Brock University in Ontario, Canada and Coordinator of Research & Instruction at the University of South Florida Libraries. Jennifer’s doctoral research focuses on representations of neurodivergence in twenty-first century middle grade fiction. Callie Hammond is a doctoral student at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, North Carolina. Callie’s doctoral research focuses on accessing historical knowledge when teaching literature that involves the Holocaust and using critical content analysis to analyze and understand representations of the Holocaust in children’s picturebooks. CLA Student Committee Members

By The Biography Clearinghouse As we come to the end of another calendar year, we reflect upon how much the world can change in just a few short months. Political turmoil, violence, and war threaten the lives of millions. Climate scientists tell us that 2023 was the hottest year on record. Devastating fires and floods ravaged cities, towns, and forests alike. These catastrophes may feel unique to our life experience, so it helps to remember that people before us have faced hardships too. Again, we turn to biographies to learn from the people among us and those who came before us. What lessons in leadership can we find? How do artists, faith leaders, scientists, activists, educators, and others work towards goals? Handle setbacks? Cope with prejudice? Persevere while facing devastation? Work collaboratively to create change? In this year-end blog entry, we share a few picture book biographies from 2022 and 2023 that were inspiring to us, as well as preview a 2024 biography. With best wishes for peace in the New Year, The Biography Clearinghouse Team

Winter Hiatus Announcement

Interrogating History, Perspective, and Nonfiction Writing with Steve Sheinkin’s "Impossible Escape"10/10/2023

By Mary Ann Cappiello & Xenia Hadjioannou on behalf of the Biography Clearinghouse  Recently, the Biography Clearinghouse interviewed author Steve Sheinkin about his latest nonfiction book, Impossible Escape: A True Story of Survival and Heroism in Nazi Europe. Action-packed and filled with dramatic tension and intricate historical details, Sheinkin shares the experiences of Rudi Vrba and Greta Sidonová, two Jewish teenagers during World War II. While the full video interview and transcript are available on our website, covering a range of questions regarding Sheinkin’s research and writing processes, we share an edited portion of it here on the CLA blog as an example of the complex decision-making that goes into writing narrative nonfiction for tween and teen readers. Interview Question As you were working on the book and revising it, how did you balance crafting a narrative that builds tension, which as you mentioned earlier, gets the reader hooked and builds the narrative towards that climactic moment, and the need for exposition, which is oftentimes in the case of this book exposition about very difficult topics? What were the moments where you knew that you had to interrupt the action, pause the action to provide that information for your readers? Steve Sheinkin’s Answer (edited for brevity): That’s doing narrative nonfiction for middle grade and YA, I think. That's my career essentially, trying to figure out how to do that…… I used to write textbooks. That's… you see how hesitant I was to confess that? But I used to write history textbooks where they don't have that problem. It's all just boring facts and figures and names and dates. And so I just don't want to ever do that. I'm still sorry and making amends for doing that. So I want it to be just story. And then I realize, wait a minute. I can’t be. I get jealous of people who write for adults because they could just say, “and then Pearl Harbor happened,” and then everyone knows what that means. I can't do that, and fair enough I shouldn't be able to, because it's unfair of me to assume that someone who's 12 or 14 has that background information, and they shouldn't have to, to pick up the book. I think that's part of what makes this, hopefully, makes one of my books valuable, is that they don't have to have background information…. I guess I hope it works that I start with just story…I am seeing all the best scenes where there's really well documented moments that have those elements of a scene that you want as a writer. .. You don't need to know them right away, but you do need to know them pretty early on, and that's why the first third of a book like this is always the hardest part. It’s kind of like a juggling act once the balls are going. It's okay. But getting them all in the air in the right order is the hard part. And so I'll write little bits of context. In this case the rise of Adolf Hitler, what the Nazis were doing. How anti-semitism was such, so central, to what the Nazis did, and and all of that… I end up writing way too much of that, and I always do, and then kind of pare it down until it starts to feel right, and I work with my editor on that kind of stuff more than any other part of the book. I don't like to write the whole thing and then send it to her. I specifically like to try to write that first third as a draft and send it to her because it's just never, never good at first. It always has that problem of being clunky, and either not starting fast enough or we're not getting to the context soon enough, and those are kind of at odds with each other. You can get it right with enough back and forth, and trial and error… It's kind of like making a movie. You film both. You film all the scenes. You don't have to decide right away what order you're gonna edit them together in, but you know they're all going to be there.

Punctuating Narrative with Exposition

Embracing Point of View in Nonfiction Writing

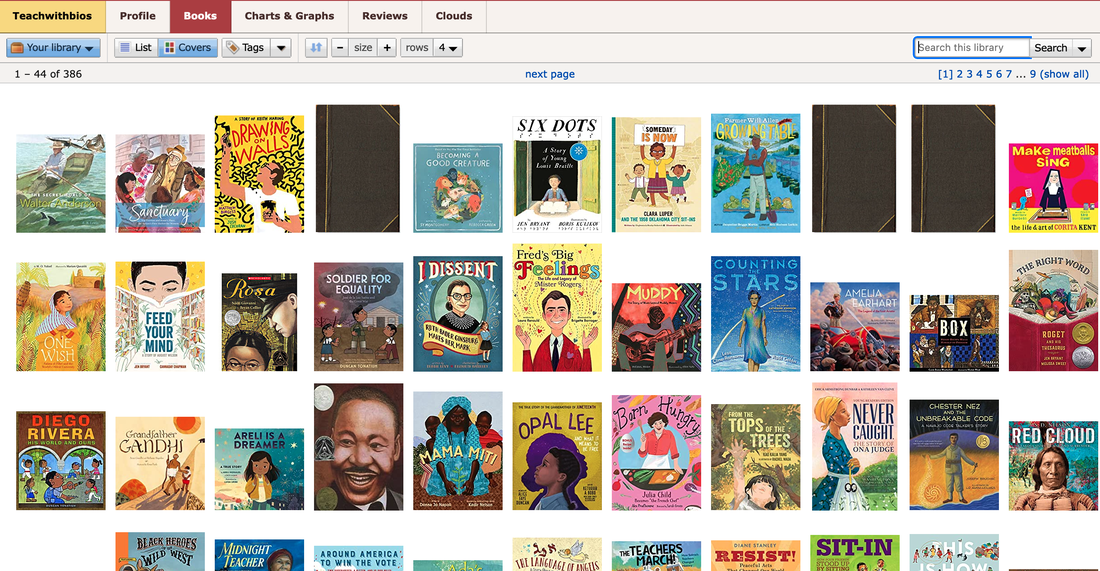

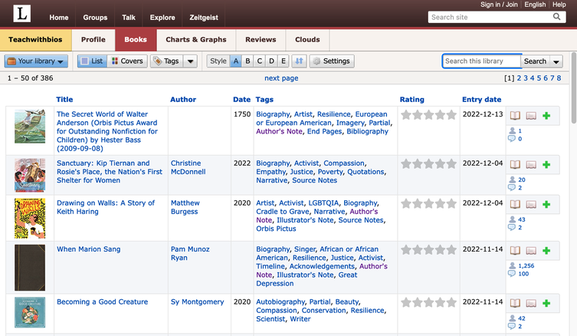

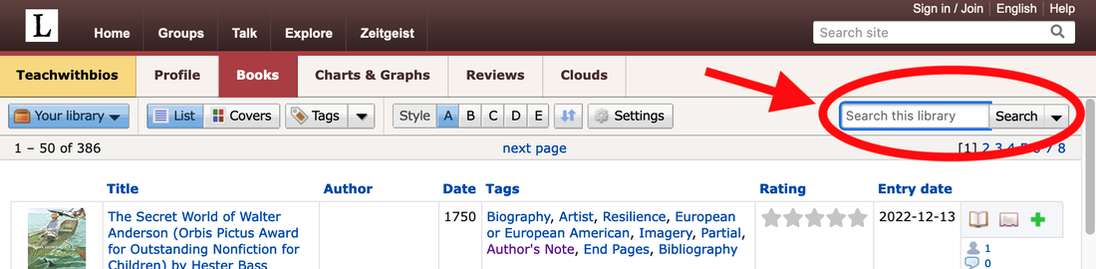

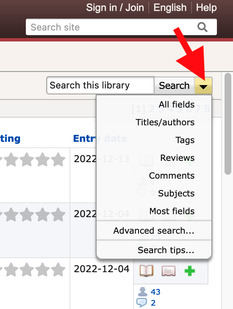

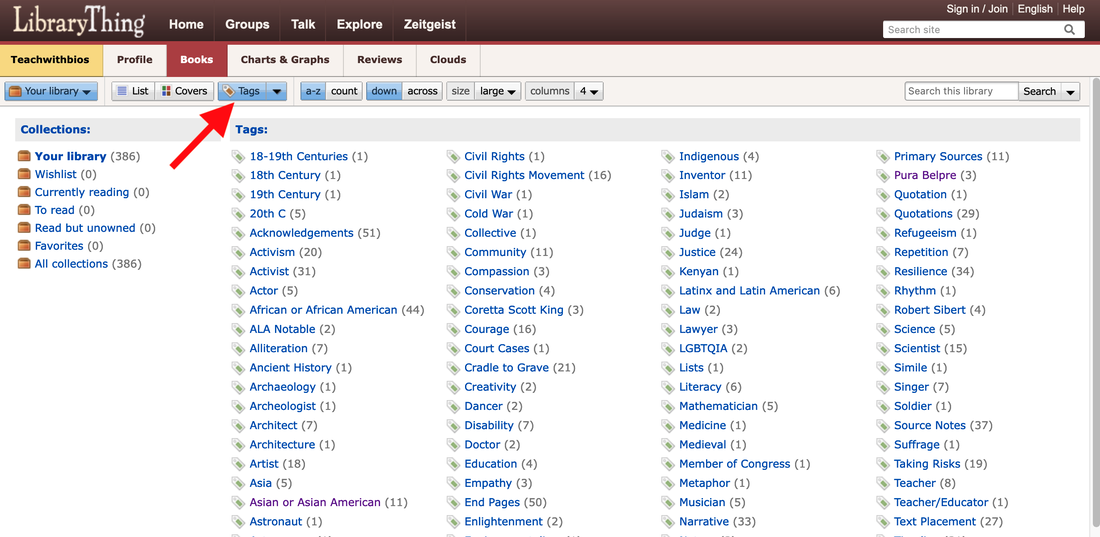

Mary Ann Cappiello teaches courses in children’s literature and literacy methods at Lesley University and is a founding member of The Biography Clearinghouse. She is co-chair of CLA's Expert Class committee and a former chair of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8. Xenia Hadjioannou is associate professor of language and literacy education at the Berks campus of Penn State University. She is president of CLA and co-editor of the CLA Blog. She is a founding member of The Biography Clearinghouse. By Xenia Hadjioannou & Mary Ann Cappiello on behalf of the Biography Clearinghouse  Wondering how to find and curate biographies suited to the interests of your students or to your curricular needs? Frustrated by a piecemeal approach, cross-referencing booklists, award lists, and Google searches? The Biography Clearinghouse has a year end gift for you! We have created a collection of biographies for young people on LibraryThing, an online book cataloging service. The collection makes use of “tags” with which users can use to guide and focus their searches. This continually updated collection is intended as a tool for educators of all subjects and age groups, librarians, and anyone else who enjoys and works with biographies. We are busily tagging the books in our collection and will continue to add and tag more titles! The best part about it? You can access our collection for free and without having to sign up for an account. You can search the collection by theme, literary elements, geographic location, format feature, profession/discipline, etc. To learn how to access, navigate, and search through the Biography Clearinghouse Collection review the information below. How do I access the Biography Clearinghouse Collection?

Simply go to https://www.librarything.com/catalog/Teachwithbios. There you will see our entire catalog listing. In the “Tags” column you will see all the tags assigned to each book by members of the Biography Clearinghouse.

How do I search through your catalog?

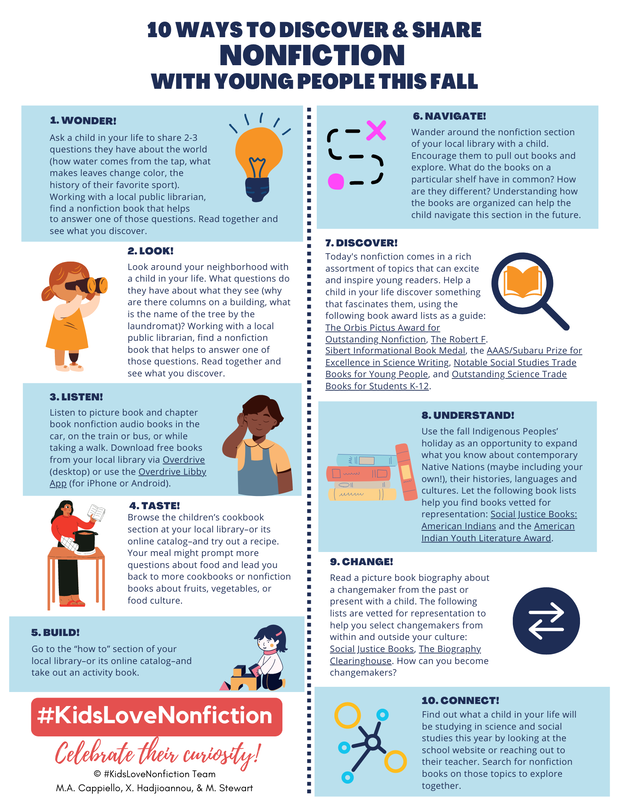

Clicking on a tag will produce a listing of all books in our catalog we have annotated with it. Have any questions? Biographies to add to our collection? Suggested tags? Please email us at [email protected]. We’d love to hear from you. Xenia Hadjioannou is an Associate Professor of Language and Literacy Education at the Berks campus of Penn State University where she teaches and works with preservice teachers through various courses in language and literacy methodology. Xenia is the co-author of Translanguaging for Emergent Bilinguals. She is the Vice President and Website Manager of the Children's Literature Assembly, and a co-editor of The CLA Blog. Mary Ann Cappiello is a Professor of Language and Literacy at Lesley University, where she teaches courses in children’s literature and literacy methods. For twelve years, she blogged about teaching with children’s literature at The Classroom Bookshelf. She is a former chair of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8. Mary Ann is the coauthor of Text Sets in Action: Pathways Through Content Area Literacy (2021). By Mary Ann Cappiello, Xenia Hadjioannou, and Melissa Stewart We are fortunate to be in the midst of a golden age for nonfiction literature for young people. Today’s nonfiction pushes boundaries in form and function, and its creators write about an ever expanding array of topics. In these books, young people encounter well-researched and nuanced explorations of cutting edge scientific discoveries, underexplored moments throughout history and in our current time, compelling accounts of historically marginalized and minoritized communities and perspectives, and more. As we advocated in our February 14, 2022, letter to The New York Times, #KidsLoveNonfiction! Indeed, several researchers investigating the reading habits and preferences of young children report that, when given the opportunity to self-select, the majority of children enjoy nonfiction as much as or more than fiction (Correia, 2011; Ives et al. 2020; Mohr, 2006; Repaskey et al., 2017). Yet, adults often assume that young people would rather read fiction, and are therefore hesitant to make nonfiction titles available to children or to devote time to exploring nonfiction with the young people in their lives. As the school year begins, we want to remind all adults who are involved in the reading lives of children that:

To raise awareness of the potential of nonfiction books to empower young people by feeding their interests and creating pathways to their passions, we’ve created the flyer 10 Ways to Discover & Share Nonfiction with Young People this Fall. We hope it will find its way onto classroom walls, library displays, and home fridges and inspire teachers, librarians, parents, and all people who read with children. Have a wonderful school year!

References Correia, M. P. (2011). Fiction vs. Informational Texts: Which Will Kindergartners Choose? Young Children, 66(6), 100–104. Ives, S. T., Parsons, S. A., Parsons, A. W., Robertson, D. A., Daoud, N., Young, C., & Polk, L. (2020). Elementary Students’ Motivation to Read and Genre Preferences. Reading Psychology, 41(7), 660–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2020.1783143 Mohr, K. A. J. (2006). Children’s Choices for Recreational Reading: A Three-Part Investigation of Selection Preferences, Rationales, and Processes. Journal of Literacy Research, 38(1), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3801_4 Repaskey, L. L., Schumm, J., & Johnson, J. (2017). First and Fourth Grade Boys’ and Girls’ Preferences For and Perceptions About Narrative and Expository Text. Reading Psychology, 38(8), 808–847. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2017.1344165 Mary Ann Cappiello teaches courses in children’s literature and literacy methods at Lesley University, blogs about teaching with children’s literature at The Classroom Bookshelf and Text Sets and Trade Books, and is a founding member of The Biography Clearinghouse. She is a former chair of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8. Xenia Hadjioannou is associate professor of language and literacy education at the Berks campus of Penn State University. She is vice-president of CLA and co-editor of the CLA Blog. She is a founding member of The Biography Clearinghouse. Melissa Stewart is the award-winning author of more than 200 science-themed nonfiction books for children and co-author of 5 Kinds of Nonfiction: Enriching Reading and Writing Instruction with Children’s Books. Her highly-regarded website features a rich array of nonfiction writing resources. By Denise Dávila on Behalf of the Biography Clearinghouse

Using Viewfinders Sister Corita Kent authored provocative multimodal compositions that were inspired by looking closely at ordinary objects and were imbued with intertextual meanings. As suggested in Make Meatballs Sing, much of her work began by focusing her attention on specific elements and blocking out others. She employed cardboard viewfinders with her students as tools for developing the skill of looking. These next activities build upon the use of viewfinders in the classroom. They are adapted from the Make Meatballs Sing Curriculum Guide.

Denise Dávila is an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin. She studies children’s literature and researches the home literacy practices of families with young children in under-resourced communities. by Kate Narita, introduction by Melissa Stewart

In February, CLA members Mary Ann Cappiello, Professor of Language and Literacy at Lesley University and Xenia Hadjioannou, Associate Professor of Language and Literacy Education at Penn State University, sent a letter signed by more than 500 educators to The New York Times asking the paper to add children's nonfiction bestseller lists to parallel the current fiction-focused lists.

The letter was also published on more than 20 blogs that serve the children's literature community--including this one—and amplified on social media as part of the #KidsLoveNonfiction campaign. (To date, more than 2,100 people have signed it.) A few weeks later, The New York Times responded, saying it had no current plans to add nonfiction lists at this time. Many people were disappointed by this decision, including fourth-grade teacher and CLA member Kate Narita, who has written the following essay, bravely sharing how the petition changed her thinking. -- Melissa Strewart Shattering My Implicit Bias Against Nonfiction by Kate Narita

Then, in January, my son mentioned a book he had read, Infinite Powers: How Calculus Reveals the Secrets of the Universe by Steven Strogatz. “Oh,” I said. “Sounds interesting. Did you read it for your calculus class?” “Yes,” he said. “And I really enjoyed it.” Did his statement about enjoying a book wake me up to my implicit bias? No. But I did feel a shift inside me. I was pleasantly surprised and excited because I love talking about books. If he had read something and was excited about it, I could read it and discuss it with him, even if he had only read it because it was a class assignment. Here was a way I could deepen my relationship with him as an adult. Even if it was just a one-time occurrence. I asked if I could read the book when he was done, and he brought it home the next time he visited. Fast forward to February break. As my husband and I were packing for a trip to Maui to celebrate our 25th wedding anniversary, he spotted Infinite Powers in the pile of books I was sorting through on our ottoman and picked it up. “What’s this?” he asked. When I explained, he asked if he could take it to Hawaii, and I nodded. I hadn’t read it yet because, to be honest, reading a whole book about calculus felt too daunting. Instead, I packed and read three books from Kate Messner’s History Smashers series and Rukhsanna Guidroz’s Samira Surfs. I also spotted a copy of Kristin Hannah’s Fly Away in our condo. Since I had watched Hannah’s Firefly Lane on Netflix and was listening to The Four Winds on Libby, I couldn’t resist picking up Fly Away, and I devoured it in a day. As my husband and I sat side-by-side reading on the beach, we talked about Infinite Powers. He told me that while he was enjoying the book, the author gave way too much credit to calculus and not nearly enough to physics. He was kind of cranky about it. Actually, he was truly irritated. I was surprised that he was having an emotional response to the book, a nonfiction book. It had stirred up passion inside him, even though it wasn’t a novel. Did his passion wake me up to my implicit bias? Not yet. But I did feel another shift. He was expressing emotion about a book, and I was listening. In the past, it had almost always been me expressing emotion about a novel and him listening.  In our almost thirty-year relationship, I could only think of one other time when he had emoted about a book. It was Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! by Richard Feynman, which I read because he had read it multiple times and was so excited about it. When we got back home, I spotted this petition (which you can still sign) on Twitter. Two professors of literacy, Mary Ann Cappiello and Xenia Hadjioannou, had written a letter asking The New York Times to add three children’s nonfiction bestseller lists—one for picture books, one for middle grade, and one for young adults. I signed it because, of course, I fully supported nonfiction writers and readers! A couple of weeks later, I saw on Facebook that, even though more than 2,000 people had signed the petition, The New York Times had refused to add children’s nonfiction bestseller lists. After a full day of teaching, I was tired, and reading this unfortunate news made me angry. I looked up from my phone. Across the room, my younger son, who was home on spring break, was reading The Elegant Universe: Superstrings, Hidden Dimensions, and the Quest for the Ultimate Theory by Brian Greene for fun because he had liked Infinite Powers so much and wanted to keep reading and learning. Next to him, my husband was reading an article about the Green Bay Packers on the internet.  In that instant, a lightbulb clicked on in my mind, and an awareness of my implicit bias washed over me like a tidal wave. My husband and younger son are readers. They have always been readers. I just didn’t realize it because narratives and fiction aren’t their jam. But give them nonfiction on topics they find fascinating—math, physics, sports—and they’re all in. They’re curious people who read to learn. They want to know about the world, how it works, and their place in it. The decisionmakers at The New York Times seem to have their own implicit bias against children’s nonfiction, and as long as they do not include lists highlighting these books, they’re failing to acknowledge the 42 percent of our youth who crave true texts. They’re also failing to open the eyes of adults who raise those kids, thinking they’re not readers. Maybe we should petition The Wall Street Journal next.

By Kathryn Will and River Lusky As we emerge from a long winter with the lengthening of days to warm the earth, I am drawn to books that get us thinking about nature–the plant and animal life in the world. As the NCBLA committee will tell you, I love books about nature, and this year many of the books we reviewed for the 2022 Notable Children’s Books in the Language Arts award list were about the natural world. For this text set we chose three books that leverage nonfiction, poetry, and a picture book to develop content knowledge, build vocabulary, and encourage divergent thinking about the natural world. They invite readers to be curious about nature in both big and small ways. Teachers can easily deepen and extend the texts through a variety of activities, and we have created a few to get you started. Wonder Walkers

If you are interested in learning more about how Micah Archer creates her collages check out the two videos below. The first provides a a brief glimpse of her printmaking, and the second offers a much more extensive look into how she creates the collage materials and assembles them for the book.

What's inside a flower and other questions about science and nature

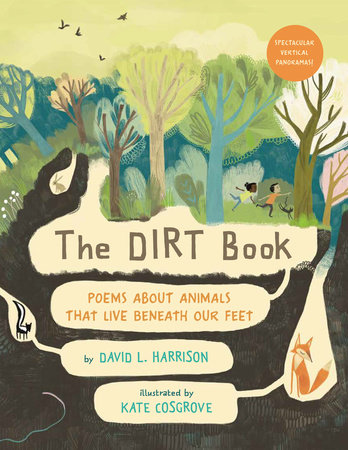

Author Read Aloud. Brightly Storytime is is a co-production of Penguin Random House. The dirt book: Poems about animals that live beneath our feet

Announcing the 2022 NCBLA list

These are just three of the 774 books the seven members of the Notable Children’s Books in Language Arts book award committee read and reviewed for consideration of selection for the 30-book list created annually. The careful analysis and rich discussions over monthly (and sometimes weekly) Zoom sessions allowed us to create a thoughtful list that meets the charge of the committee.

The charge of the seven-member national committee is to select 30 books that best exemplify the criteria established for the Notables Award. Books considered for this annual list are works of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry written for children, grades K-8. The books selected for the list must:

2022 NCBLA Committee members

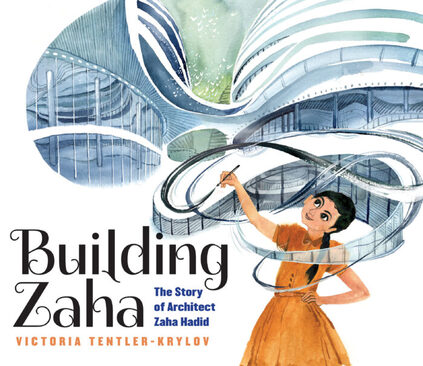

Kathryn Will, Chair (University of Maine Farmington) @KWsLitCrew Vera Ahihya (Brooklyn Arbor Elementary School) @thetututeacher Patrick Andrus (Eden Prairie School District, Minnesota) @patrickontwit Dorian Harrison (Ohio State University at Newark) Laretta Henderson (Eastern Illinois University) @EIU_PKthru12GEd Janine Schall (The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley) Fran Wilson (Madeira Elementary School, Ohio) @mrswilsons2nd *All NCBLA Committee members are members of CLA Kathryn Will is Assistant Professor Literacy at the University of Maine Farmington. She served as Chair of the 2022 Notable Children’s Books in Language Arts committee. River Lusky is an undergraduate student at the University of Maine Farmington. By Julie Waugh and Erika Thulin Dawes on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse.  March is Women’s History month and picturebook biographies are a powerful way to recognize and celebrate the accomplishments of women. In the most recent Biography Clearinghouse entry, we explore Victoria Tentler-Krylov’s picture book biography Building Zaha: The Story of Architect Zaha Hadid. As a child, Zaha Hadid was fascinated by aspects of her surroundings that others passed by without observing. Her eye for the beauty in nature developed into a vision for architecture that challenged existing perceptions of what a building could be. In Building Zaha, Victoria Tentler-Krylov describes how these seeds of interest planted in childhood grew into a career and a passionate commitment to an artform. Tentler-Krylov’s water illustrations soar across the page, lifting readers into Zaha’s vision of what humankind’s structures might aspire to be. In the Biography Clearinghouse entry for Building Zaha, you will find an interview, in which Victoria Tentler-Krylov describes how her own education as an architect influenced her writing of Zaha Hadid’s story. You’ll find teaching ideas that focus on character development, mentoring, and goal setting, as well as ideas that build content knowledge about the relationship between architecture and nature, the design processes of architecture, and women leaders in the field. Like us, you will be inspired by the lessons that author/ illustrator Victoria Tentler-Krylov learned from studying the life of Zaha Hadid: “Trust your own voice. Trust your own vision.” Here is an excerpt of the teaching ideas in the Biography Clearinghouse entry for Building Zaha: Exploring Zaha’s Designs  Zaha Hadid became known as “the queen of the curve” in the architecture world. She created buildings with shapes that people thought impossible to build. Invite students to explore, notice, and wonder with Zaha Hadid’s amazing projects:

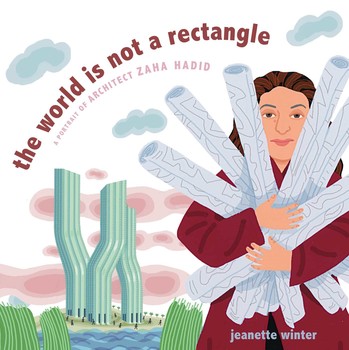

Another recent children's book biography about Zaha Hadid is The World is Not a Rectangle by Jeanette Winter. Winter’s book focuses heavily on how Zaha Hadid’s work is influenced by the natural world, whereas Tentler-Krylov’s book focuses more on Zaha the person. The paired texts could provide a powerful invitation for students to compare and contrast the different ways in which authors made choices about how to share a person’s life in picture book format. Breaking Boundaries: Female Architects

Designing for Form and Function: Thinking Like an Architect Victoria Tentler-Krylov shared how one of her favorite illustrations in Building Zaha is the spread where a young Zaha is the only character in a crowded space who is looking up in a beautiful mosque. Looking closely and wondering can help you think and work like an architect. Looking closely and wondering can also help you focus on form (what a space looks like) in architecture, and how well that form meets function (what is going to happen in the designed space). Form and function are ideas that need to work hand in hand for an architect to create a successful place to live or work. Some people told Zaha Hadid that form was more important to her than function. She was criticized that her creative, uniquely designed spaces did not use space as well as they could, or did not use space as efficiently as possible. This was part of why, early in her career, people told Zaha that she would only be a “paper architect” - an architect that would only have designs on paper and not made into buildings.

Erika Thulin Dawes is Professor of Language and Literacy at Lesley University where she teaches courses in children’s literature and early childhood literacy. She blogs about teaching with children’s literature at The Classroom Bookshelf, a School Library Journal blog, and is a former chair of NCTE’s Charlotte Huck Award for Outstanding Fiction for Children. Julie Waugh teaches 8th grade ELA at Smith Junior High and serves as an Inquiry Coach for Mesa Public Schools. She delights in the company of children surrounded and inspired by books. A longtime member of NCTE, and an enthusiastic newer member of CLA, Julie is a former committee member of NCTE's Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction for Children.

LETTER TO THE NEW YORK TIMES

Nonfiction books for young people are in a golden age of creativity, information-sharing, and reader-appeal. But the genre suffers from an image problem and an awareness problem. The New York Times can play a role in changing that by adding a set of Nonfiction Best Seller lists for young people: one for picture books, one for middle grade literature, and one for young adult literature.

Today’s nonfiction authors and illustrators are depicting marginalized and minority communities throughout history and in our current moment. They are sharing scientific phenomena and cutting-edge discoveries. They are bearing witness to how art forms shift and transform, and illuminating historical documents and artifacts long ignored. Some of these book creators are themselves scientists or historians, journalists or jurists, athletes or artists, models of active learning and agency for young people passionate about specific topics and subject areas. Today’s nonfiction continues to push boundaries in form and function. These innovative titles engage, inform, and inspire readers from birth to high school. Babies delight in board books that offer them photographs of other babies’ faces. Toddlers and preschoolers fascinated by the world around them pore over books about insects, animals, and the seasons. Children, tweens, and teens are hungry for titles about real people that look like them and share their religion, cultural background, or geographical location, and they devour books about people living different lives at different times and in different places. Info-loving kids are captivated by fact books and field guides that fuel their passions. Young tinkerers, inventors, and creators seek out how-to books that guide them in making meals, building models, knitting garments, and more. Numerous studies have described such readers and their passionate interest in nonfiction (Jobe & Dayton-Sakari, 2002; Moss and Hendershot, 2002; Mohr, 2006). Young people are naturally curious about their world. When they are allowed to follow their passions and explore what interests them, it bolsters their overall wellbeing. And the more young people read, the more they grow as readers, writers, and critical thinkers (Allington & McGill-Franzen, 2021; Van Bergen et al., 2021). Research provides clear evidence that many children prefer nonfiction for their independent reading, and many more select it to pursue information about their particular interests (Doiron, 2003; Repaskey et al., 2017; Robertson & Reese, 2017; Kotaman & Tekin, 2017). Creative and engaging nonfiction titles can also enhance and support science, social studies, and language arts curricula. And yet, all too often, children, parents, and teachers do not know about recently published nonfiction books. Bookstores generally have only a few shelves devoted to the genre. And classroom and school library book collections remain dominated by fiction. If families, caregivers, and educators were aware of the high-quality nonfiction that is published for children every year, the reading lives of children and their educational experiences could be significantly enriched. How can The New York Times help resolve the gap between readers’ yearning for engaging nonfiction, on the one hand, and their lack of knowledge of its existence, on the other? By maintaining separate fiction and nonfiction best seller lists for young readers just as the Book Review does for adults. The New York Times Best Sellers lists constitute a vital cultural touchstone, capturing the interests of readers and trends in the publishing world. Since their debut in October of 1931, these lists have evolved to reflect changing trends in publishing and to better inform the public about readers’ habits. We value the addition of the multi-format Children’s Best Seller list in July 2000 and subsequent lists organized by format in October 2004. Though the primary purpose of these lists is to inform, they undeniably play an important role in shaping what publishers publish and what children read. Adding children’s nonfiction best-seller lists would:

We, the undersigned, strongly believe that by adding a set of nonfiction best-seller lists for young people, The New York Times can help ensure that more children, tweens, and teens have access to books they love. Thank you for considering our request. Dr. Mary Ann Cappiello Professor, Language and Literacy Graduate School of Education, Lesley University Cambridge, Massachusetts Former Chair, National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction Committee, Blogger at The Classroom Bookshelf of School Library Journal, Founding Member of The Biography Clearinghouse. Dr. Xenia Hadjioannou Associate Professor, Language and Literacy Education Penn State University, Harrisburg Campus Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Vice President of the Children’s Literature Assembly (CLA) of the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE), co-editor of The CLA Blog, Founding Member of The Biography Clearinghouse. References

Allington, R. L., & McGill-Franzen, A. M. (2021). Reading volume and reading achievement: A review of recent research. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S231–S238. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.404 Correia, M. (2011). Fiction vs. informational texts: Which will your kindergarteners choose? Young Children, 66(6), 100-104. Doiron, R. (2003). Boy books, girl books: Should we re-organize our school library collections? Teacher Librarian, 30(3), 14. Kotaman H. & Tekin A.K. (2017). Informational and fictional books: young children's book preferences and teachers' perspectives. Early Child Development and Care, 187(3-4), 600-614, DOI: 10.1080/03004430.2016.1236092 Jobe, R., & Dayton-Sakari, M. (2002). Infokids: How to use nonfiction to turn reluctant readers into enthusiastic learners. Pembroke. Mohr, K. A. J. (2006). Children’s choices for recreational reading: A three-part investigation of selection preferences, rationales, and processes. Journal of Literacy Research, 38(1), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3801_4 Moss, B. & Hendershot, J. (2002). Exploring sixth graders' selection of nonfiction trade books: when students are given the opportunity to select nonfiction books, motivation for reading improves. The Reading Teacher, 56 (1), 6-17. Repaskey, L., Schumm, J. & Johnson, J. (2017). First and fourth grade boys’ and girls’ preferences for and perceptions about narrative and expository text. Reading Psychology, 38(8), 808-847. Robertson, Sarah-Jane L. & Reese, Elaine. (2017). The very hungry caterpillar turned into a butterfly: Children's and parents' enjoyment of different book genres. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 17(1), 3-25. Van Bergen, E., Vasalampi, K., & Torppa, M. (2021). How are practice and performance related? Development of reading from age 5 to 15. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(3), 415–434. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.309. If you support the request to add three children's nonfiction bestseller lists to parallel the existing picture book, middle grade, and young adult lists, which focus on fiction, please add your name and affiliation to the signature collection form. |

Authors:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CLA

About CLA

|

Journal of Children's Literature

Write for JCL

|

ResourcesCLA-sponsored NCTE Position Statements

|

Members-Only Content

CLA Video Library

|

© COPYRIGHT 2018.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed