By Jennifer M. Graff, Jenn Sanders, and Courtney Shimek on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse

A Sampling of Wu Chien Shiung’s Accomplishments and Accolades |

| The first woman to

She also received

The Biography Clearinghouse’s latest entry includes interdisciplinary teaching ideas and resources that

This entry also features interviews with Robeson and Huang about their inspirations for this picturebook biography, connections to Wu Chien Shiung, and details about their research and composing processes, among other interesting topics. Below are three instructional ideas from this entry. |

Mentoring Via Peer Conferencing

Teach the mentor/tutor to pay attention to the writer’s ideas before worrying about spelling conventions.

“Respect the writer and the writer’s paper.”

Make the writer feel comfortable, be an active listener, and don’t write on the person’s paper.

“Involve the writer by asking questions.”

Teach mentors/tutors to ask open ended questions that get the writer talking about their ideas, their writing purpose, or their process.

“Teach the writer.”

Mentors/tutors share writing strategies that can be applied to the current piece but also across other pieces, rather than just trying to fix or revise the one piece they are discussing.

“Encourage the writer.”

Mentors/tutors provide encouragement by noting something specific that the writer did really well and offering one or two suggestions for revision (p.127).

Teachers can also invite students to consider the role of mentorship in their own lives. Students can identify individuals who have served as mentors to them and explore mentorship patterns and practices that are helpful and empowering to them as learners.

Advocacy and Activism

- Yuri Kochiyama was a political activist from California who fought with Malcom X to work for racial justice, civil and human rights, and anti-war movements. She went on to work in the redress and reparations movements for Japanese Americans and continued to fight for political prisoners until she passed away in 2014.

- Pranjal Jain is an Indian-American activist who has been organizing since she was 12 years old. As a current undergraduate at Cornell University, she is the founder of Global Girlhood, a women-led organization that inspires intercultural and intergenerational dialogue in online and offline spaces.

- Stephanie Hu is a Chinese American who founded Dear Asian Youth while she was a high school student as a support website for marginalized young people as a result of the rise in anti-Asian racism and violence during the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Anna May Wong was the first Chinese American movie star to appear in U.S. box offices. Although she was often relegated to smaller roles that perpetuated Asian stereotypes, her career spanned silent films, talkies, theater, and television, and she helped blaze the trail for Asian American performers after her. See Paula Yoo and Lin Yang’s (2009) picturebook biography, Shining Star: The Anna May Wong Story, published by Lee & Low Books.

Printmaking a Character for Fiction Writing

By using basic supplies such as styrofoam plates and markers for printmaking, students can create a character to print and use in their own creative story. Watch this short video of a teacher demonstrating the styrofoam printmaking process.

If you have 1-2 hours…. |

If you have 1-2 days… |

If you have 1-2 weeks… |

Each student can design a main character for a story they write, and then draw and marker-print the character on paper. In this activity, students will experience a process of printmaking that helps them understand the steps and all the work that goes into making printed images. |

After students create their printed character (see the If you have 1 to 2 hours . . . column), students can draft the story in which their character experiences a problem, challenge, or adventure. Based on their story, they can add a background setting in their picture to place their character in the context of their story. Students will simply draw the background setting and objects around their character on their printed picture. |

Students can print their character four to six times, on separate pieces of paper, to create a storyboard with multiple scenes. Save one of these prints to make a title page for the story. For this activity, we recommend students leave the background of the styrofoam plate empty so they can draw in different backgrounds as the story progresses. Then, they can divide their corresponding written story into sections (three, four, or five, depending on the number of prints they made). For each story section, they can draw in a related background setting, additional characters, or objects to help complete the scene. In the end, they will have a multimedia print that has their character marker-printed and the background drawn in with pen, marker, or other tools. |

Reference

Jennifer Sanders is a Professor of Literacy Education at Oklahoma State University, specializing in representations of diversity in children’s and young adult literature and writing pedagogy. She is co-founder and co-chair of The Whippoorwill Book Award for Rural YA Literature and long-time member of CLA.

Courtney Shimek is an Assistant Professor in the department of Curriculum & Instruction/Literacy Studies at West Virginia University. She has been a CLA member since 2015.

by Rachel Skrlac Lo & Donna Sabis-Burns on behalf of the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee

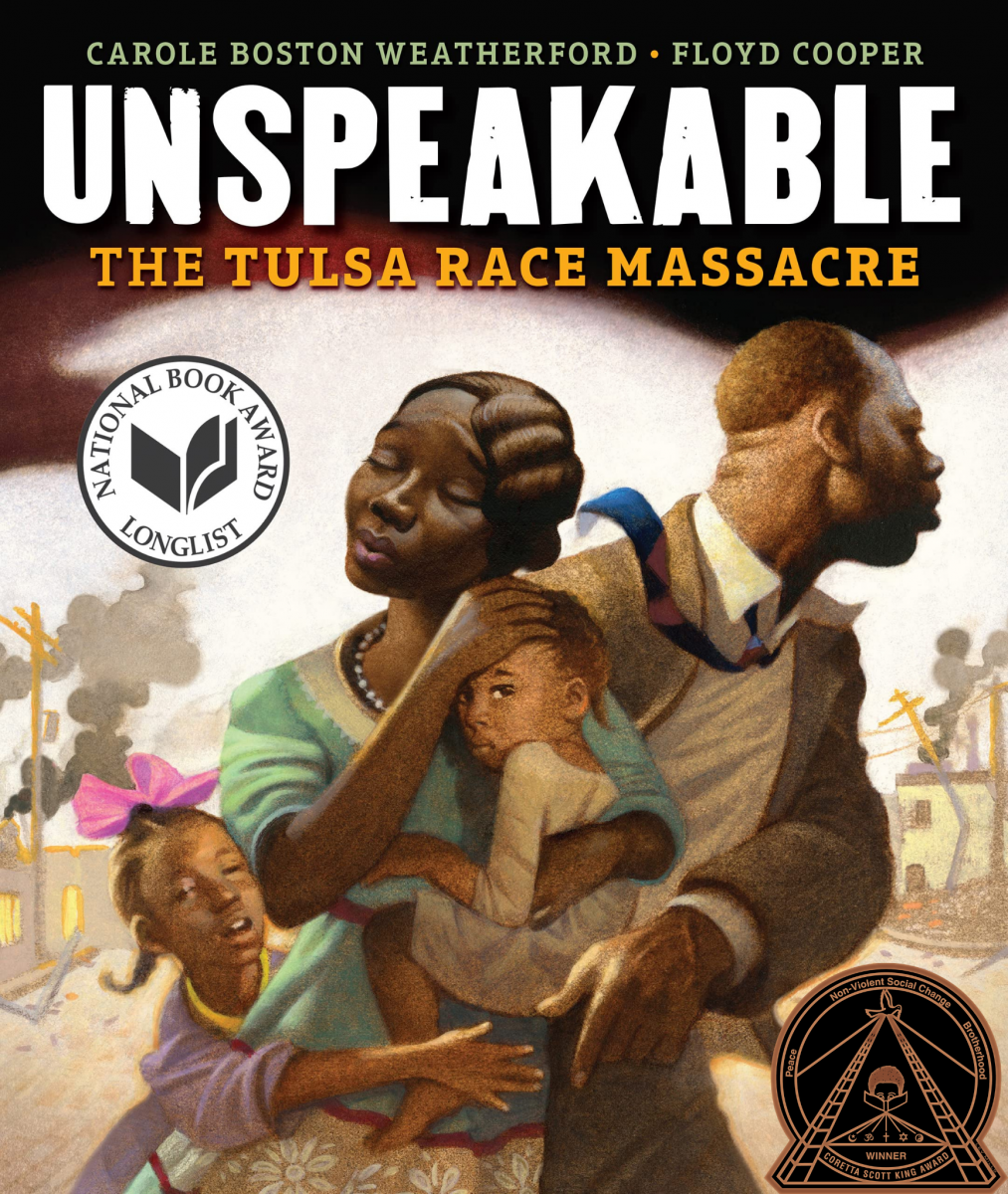

Challenges to books and reading lists are proliferating. In recent conversations with students, educators, and school board members, folks have shared that book challenges are taking up valuable time, distracting from and interfering with learning, and creating new tensions in the classroom and in the boardroom. Students are denied access to texts while challenged books undergo reviews, and they often have no say over districts’ decisions. Teachers are asked to modify carefully constructed curriculum or face discipline. Administrators are drawing on policies that were not designed for this onslaught of challenges. According to the American Library Association, in 2021 George/Melissa (Gino) and Stamped (Reynolds & Kendi) were the two most challenged books. Jason Reynolds decries these challenges for denying children access to books. These books are in good company. Gender Queer (Kobabe), Maus (Spiegelman), New Kid (Craft), Fry Bread (Maillard) are a few titles on a quickly growing list. These challenges represent the carefully organized efforts of several groups, such as Moms for Liberty and Parents Defending Education, groups that purport to work for “the restoration of a healthy, non-political education for our kids”. Their goal is to incite moral panic and culture wars, framed as protecting innocent children from harm. This notion of harm is narrowly defined, namely to protect white heteronormative conservative families from having to acknowledge a broader world. Critics of these book challenges include storytellers, educators and librarians, teacher educators and other scholars, and students. Books provide access to new worlds and perspectives. They may challenge our beliefs or affirm them. They may disgust us, enrapture us, and all the places in between. A good library and curriculum has books that do all of these things. In schools, books are used to help us navigate the world and build our ability to think critically about who we all are. Book challenges deny all students the rights to access new worlds and develop these skills to critically interrogate their world. |

Institutional Resources to Reject Book Challenges

The NEA’s Code of Ethics, briefly

1. “restrain the student from independent action in the pursuit of learning”,

2. “unreasonably deny the student’s access to varying points of view”, nor

3. “deliberately suppress or distort subject matter”.

Additionally, educators must make an effort to:

4. “protect students from harmful conditions”,

5. “not intentionally expose the student to embarrassment or disparagement”, and

6. ensure all students have access to programs, benefits, and advantages regardless of “race, color, creed, sex, national origin, marital status, political or religious beliefs, family, social or cultural background or sexual orientation.”

The two remaining conditions are that educators:

7. do not seek private advantage from relationships with students, and

8. will respect students' privacy.

Using the Code of Ethics to Respond to Challenges

The adults behind the book challenges argue their children are harmed through the content of these books, and this harm can be manifested as feelings of discomfort, shame and embarrassment, or in exposure to ideas that may lead to “deviance”. According to Principle 1, then, these parents are claiming that being exposed to these books is a harmful condition (condition 4) that results in these children feeling embarrassed and disparaged whether due to sexual content of texts, such as in challenges to George/Melissa, or discovering the longstanding persistent impact of white supremacy, such as in Stamped (condition 5).

Yet, if schools were to succumb to these challenges, the result would be changes to curriculum and school resources that would unfairly deny benefits (condition 6) to students who identify differently from the mostly white, mostly straight, mostly Christian, mostly politically conservative, mostly American parents who are leading these challenges. Moreover, by shifting school curriculum and materials based on this loud but small group, schools would further violate the code of ethics by restraining independent action (condition 1), such as access to a diverse and representative library collection. Students would be denied access to multiple points of view (condition 2) by restricting the scope of content and voices. This suppression would distort subject matter (condition 3) and would impede student progress (condition 6). Removing books based on outcry of a small but politically-motivated group violates most of the conditions of commitment to the student in the NEA’s code of ethics.

Additionally, because educators must respect students’ privacy (condition 8), educators are guided by an ethical duty to protect students' identities because students warrant this protection of their full humanity. As such, educators must not be compelled to reveal which students need access to these books. We must trust educators when they say there are children who need these books.

So, which students need access to these books?

As CLA’s Position Statement on the Importance of Critical Selection and Teaching of Diverse Children’s Literature underscores:

Resisting book challenges, then, is not about supporting or denying an ideological position. It’s affirming our commitment to serve all students. By drawing on a code of ethics, or other institutional materials, educators can respond to these challenges with the support of their profession and an understanding that their desire to serve all students is morally and ethically just.

Donna Sabis-Burns, Ph.D., an enrolled citizen of the Upper Mohawk-Turtle Clan, is a Group Leader in the Office of Indian Education at the U.S. Department of Education* in Washington, D.C. She is a Board Member (2020-2022) with the Children's Literature Assembly and Co-Chair of the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusivity Committee.

| This morning, Mary Ann Cappiello, Professor of Language and Literacy at Lesley University, and Xenia Hadjioannou, Associate Professor of Language and Literacy Education at the Harrisburg campus of Penn State University and co-editor of the CLA Blog, sent the letter below to The New York Times requesting that the paper add three children's nonfiction bestseller lists to parallel the existing picture book, middle grade, and young adult lists, which focus on fiction. The submitted letter included the signatures of more than 500 educators and librarians, as well as the institutional signatures of the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE), the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, and the Children’s Literature Assembly of NCTE. This change will align the children's lists with the adult bestseller lists, which separate nonfiction and fiction. It will also acknowledge the incredible vibrancy of children's nonfiction available today and support the substantial body of research showing that many children prefer nonfiction and still others enjoy fiction and nonfiction equally. If you support this request, please follow the signature collection form link to add your name and affiliation to the more than 500 educators and librarians who have already endorsed the effort. Your information will be added to the letter but your email address will remain private. |

LETTER TO THE NEW YORK TIMES

Today’s nonfiction authors and illustrators are depicting marginalized and minority communities throughout history and in our current moment. They are sharing scientific phenomena and cutting-edge discoveries. They are bearing witness to how art forms shift and transform, and illuminating historical documents and artifacts long ignored. Some of these book creators are themselves scientists or historians, journalists or jurists, athletes or artists, models of active learning and agency for young people passionate about specific topics and subject areas. Today’s nonfiction continues to push boundaries in form and function. These innovative titles engage, inform, and inspire readers from birth to high school.

Babies delight in board books that offer them photographs of other babies’ faces. Toddlers and preschoolers fascinated by the world around them pore over books about insects, animals, and the seasons. Children, tweens, and teens are hungry for titles about real people that look like them and share their religion, cultural background, or geographical location, and they devour books about people living different lives at different times and in different places. Info-loving kids are captivated by fact books and field guides that fuel their passions. Young tinkerers, inventors, and creators seek out how-to books that guide them in making meals, building models, knitting garments, and more. Numerous studies have described such readers and their passionate interest in nonfiction (Jobe & Dayton-Sakari, 2002; Moss and Hendershot, 2002; Mohr, 2006). Young people are naturally curious about their world. When they are allowed to follow their passions and explore what interests them, it bolsters their overall wellbeing. And the more young people read, the more they grow as readers, writers, and critical thinkers (Allington & McGill-Franzen, 2021; Van Bergen et al., 2021).

Research provides clear evidence that many children prefer nonfiction for their independent reading, and many more select it to pursue information about their particular interests (Doiron, 2003; Repaskey et al., 2017; Robertson & Reese, 2017; Kotaman & Tekin, 2017). Creative and engaging nonfiction titles can also enhance and support science, social studies, and language arts curricula. And yet, all too often, children, parents, and teachers do not know about recently published nonfiction books. Bookstores generally have only a few shelves devoted to the genre. And classroom and school library book collections remain dominated by fiction. If families, caregivers, and educators were aware of the high-quality nonfiction that is published for children every year, the reading lives of children and their educational experiences could be significantly enriched.

How can The New York Times help resolve the gap between readers’ yearning for engaging nonfiction, on the one hand, and their lack of knowledge of its existence, on the other? By maintaining separate fiction and nonfiction best seller lists for young readers just as the Book Review does for adults.

The New York Times Best Sellers lists constitute a vital cultural touchstone, capturing the interests of readers and trends in the publishing world. Since their debut in October of 1931, these lists have evolved to reflect changing trends in publishing and to better inform the public about readers’ habits. We value the addition of the multi-format Children’s Best Seller list in July 2000 and subsequent lists organized by format in October 2004. Though the primary purpose of these lists is to inform, they undeniably play an important role in shaping what publishers publish and what children read.

Adding children’s nonfiction best-seller lists would:

- Help family members, caregivers, and educators identify worthy nonfiction titles.

- Provide a resource for bibliophiles—including book-loving children—of materials that satisfy their curiosity.

- Influence publishers’ decision-making.

- Inform the public about innovative ways to convey information and ideas through words and images.

- Inspire schools and public libraries to showcase nonfiction, broadening its appeal and deepening respect for truth.

We, the undersigned, strongly believe that by adding a set of nonfiction best-seller lists for young people, The New York Times can help ensure that more children, tweens, and teens have access to books they love. Thank you for considering our request.

Dr. Mary Ann Cappiello

Professor, Language and Literacy

Graduate School of Education, Lesley University

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Former Chair, National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction Committee, Blogger at The Classroom Bookshelf of School Library Journal, Founding Member of The Biography Clearinghouse.

Dr. Xenia Hadjioannou

Associate Professor, Language and Literacy Education

Penn State University, Harrisburg Campus

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

Vice President of the Children’s Literature Assembly (CLA) of the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE), co-editor of The CLA Blog, Founding Member of The Biography Clearinghouse.

References

Correia, M. (2011). Fiction vs. informational texts: Which will your kindergarteners choose? Young Children, 66(6), 100-104.

Doiron, R. (2003). Boy books, girl books: Should we re-organize our school library collections? Teacher Librarian, 30(3), 14.

Kotaman H. & Tekin A.K. (2017). Informational and fictional books: young children's book preferences and teachers' perspectives. Early Child Development and Care, 187(3-4), 600-614, DOI: 10.1080/03004430.2016.1236092

Jobe, R., & Dayton-Sakari, M. (2002). Infokids: How to use nonfiction to turn reluctant readers into enthusiastic learners. Pembroke.

Mohr, K. A. J. (2006). Children’s choices for recreational reading: A three-part investigation of selection preferences, rationales, and processes. Journal of Literacy Research, 38(1), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3801_4

Moss, B. & Hendershot, J. (2002). Exploring sixth graders' selection of nonfiction trade books: when students are given the opportunity to select nonfiction books, motivation for reading improves. The Reading Teacher, 56 (1), 6-17.

Repaskey, L., Schumm, J. & Johnson, J. (2017). First and fourth grade boys’ and girls’ preferences for and perceptions about narrative and expository text. Reading Psychology, 38(8), 808-847.

Robertson, Sarah-Jane L. & Reese, Elaine. (2017). The very hungry caterpillar turned into a butterfly: Children's and parents' enjoyment of different book genres. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 17(1), 3-25.

Van Bergen, E., Vasalampi, K., & Torppa, M. (2021). How are practice and performance related? Development of reading from age 5 to 15. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(3), 415–434. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.309.

By Bettie Parsons Barger and Jennifer M. Graff

See the USBBY website for additional content and presentation considerations. |

As we look at the past three years of OIB lists, we recognize how our current realities are reflected in the committees’ selections. Julie Flett’s (2021) We All Play/ Kimêtawânaw illustrates humans’ innate connection to nature and the joyous experiences of playing outdoors, as the current pandemic has encouraged. The Elevator (Frankel, 2020) speaks to the power of humorous storytelling to unite strangers who unexpectedly find themselves in close quarters. The current Ukrainian-Russian tensions mirror the conflict in How War Changed Rondo (2021). Silvia Vecchini’s (2019) graphic novel, The Red Zone: An Earthquake Story, and Heather Smith’s (2019) picturebook, The Phone Booth in Mr. Hirota’s Garden, are stirring testimonies about ongoing global natural disasters, such as the recent volcano eruption and subsequent earthquake and tsunami that have devastated the Pacific nation of Tonga.

Partnering the beliefs that books including hostile and traumatic events “can provoke reflection and inspire dialogue that sensitizes readers . . .” (Raabe, 2016, p.58) and that “stories are important bridging stones; they can bring people closer together, connect them, and help overcome alienation” (Raabe & von Merveldt, 2018, p.64), we created a sampling of five text sets that can be readily used in K-12 classrooms.

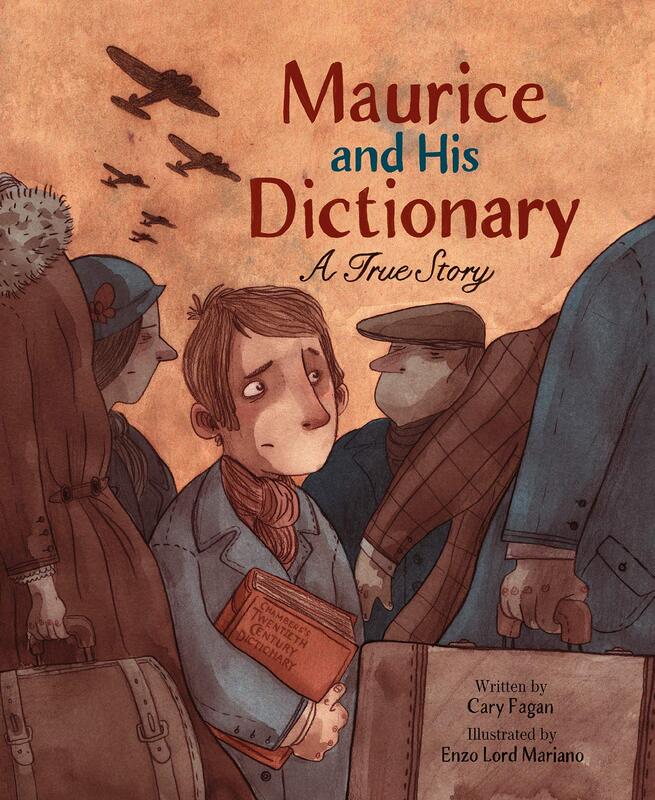

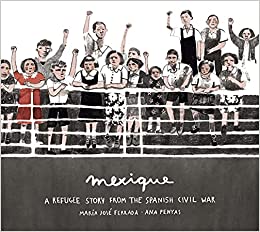

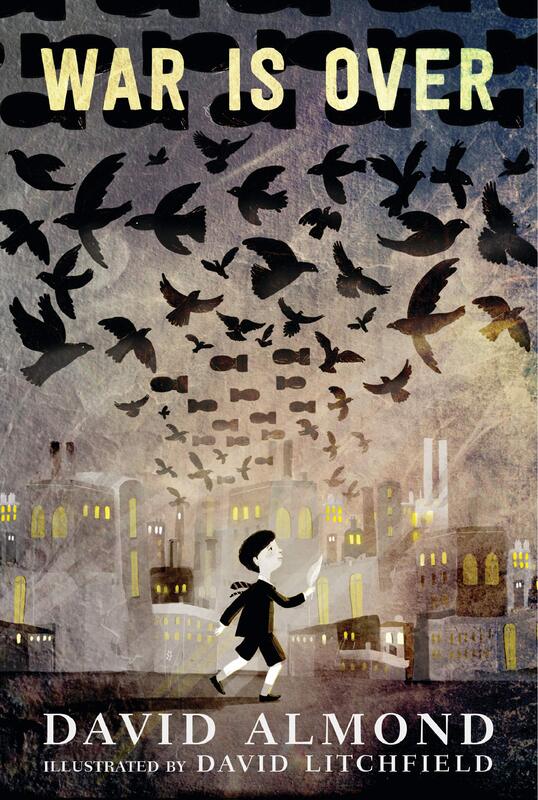

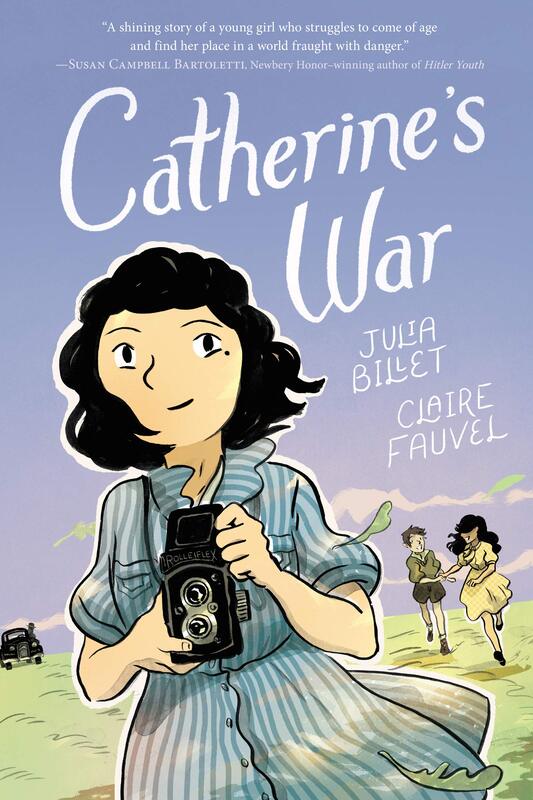

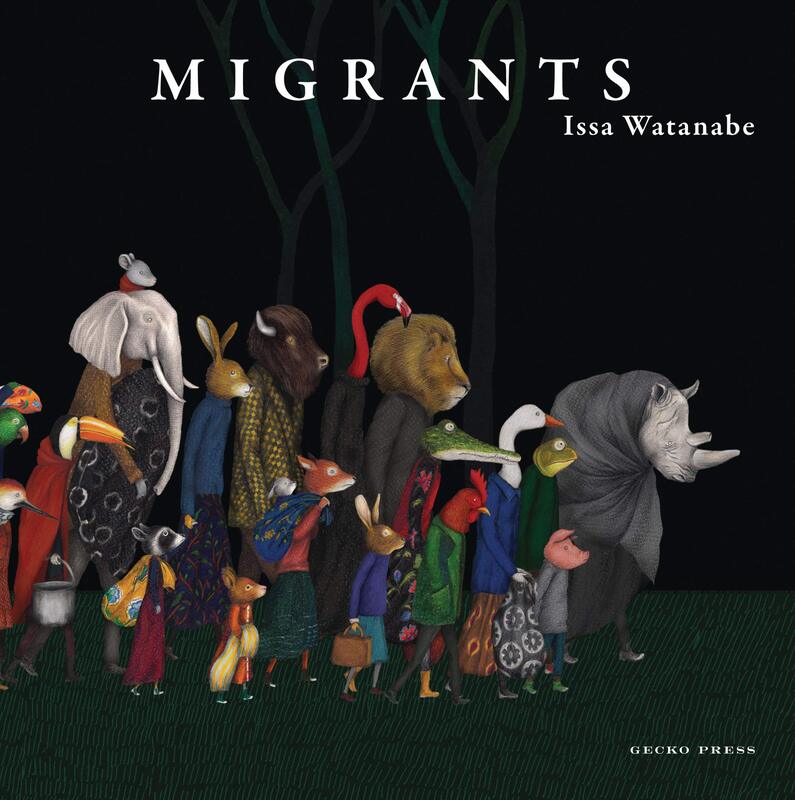

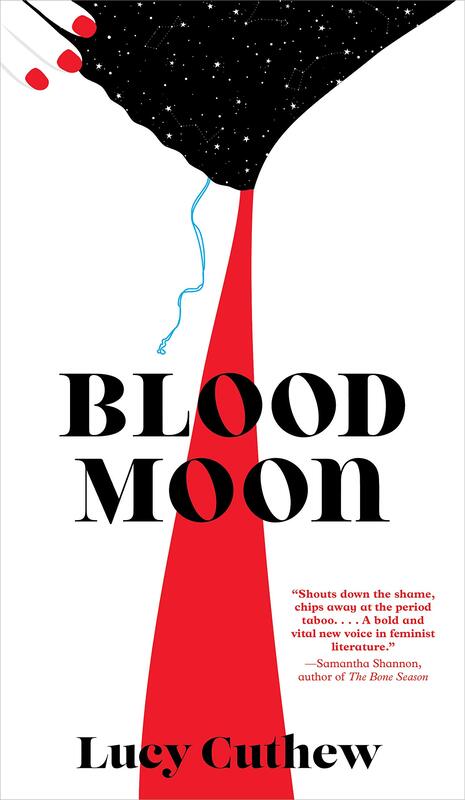

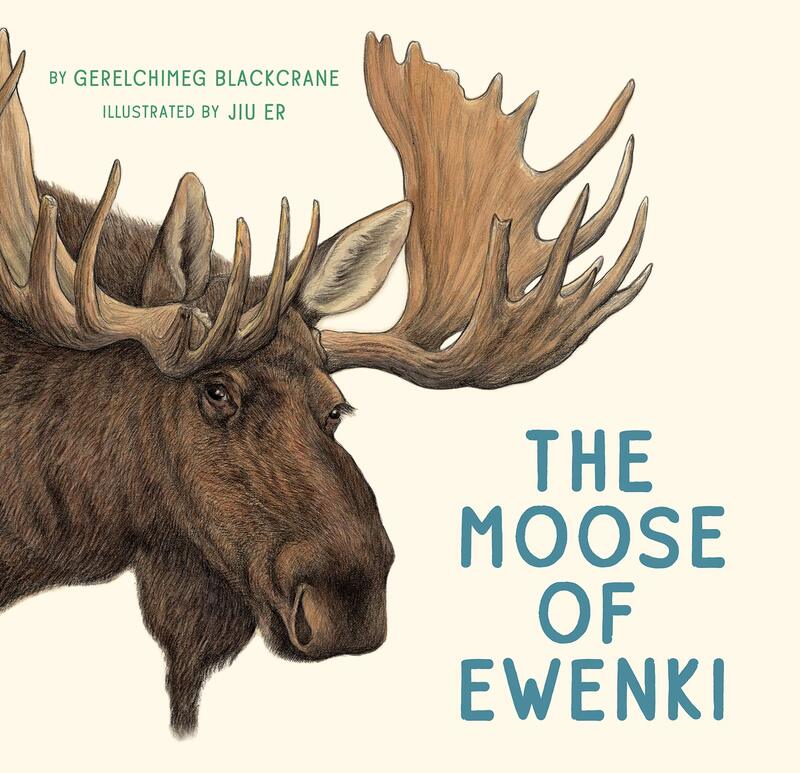

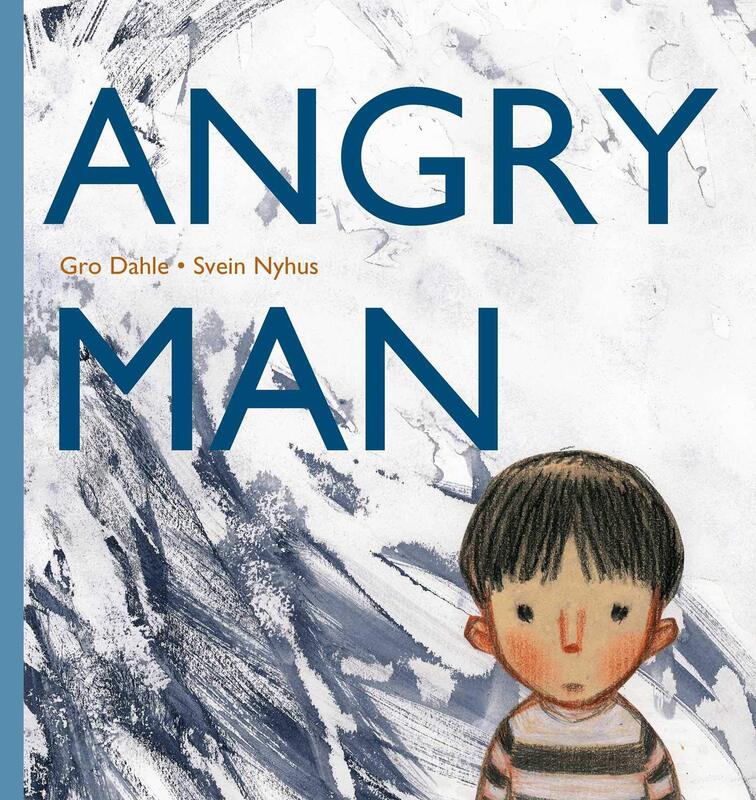

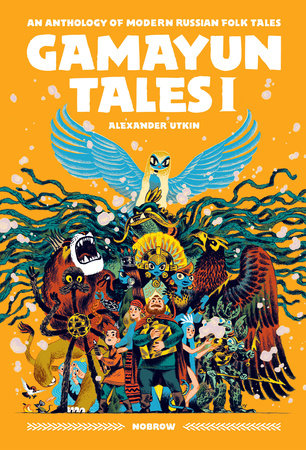

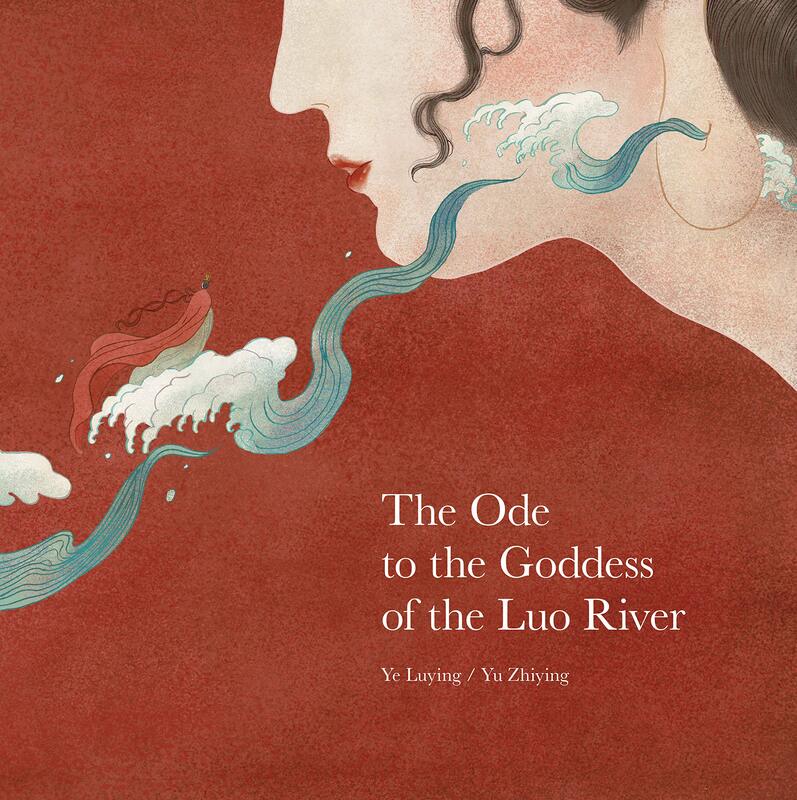

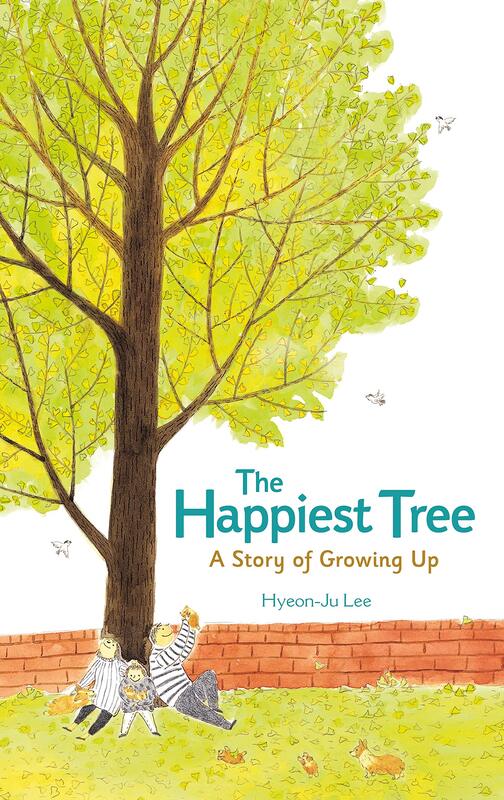

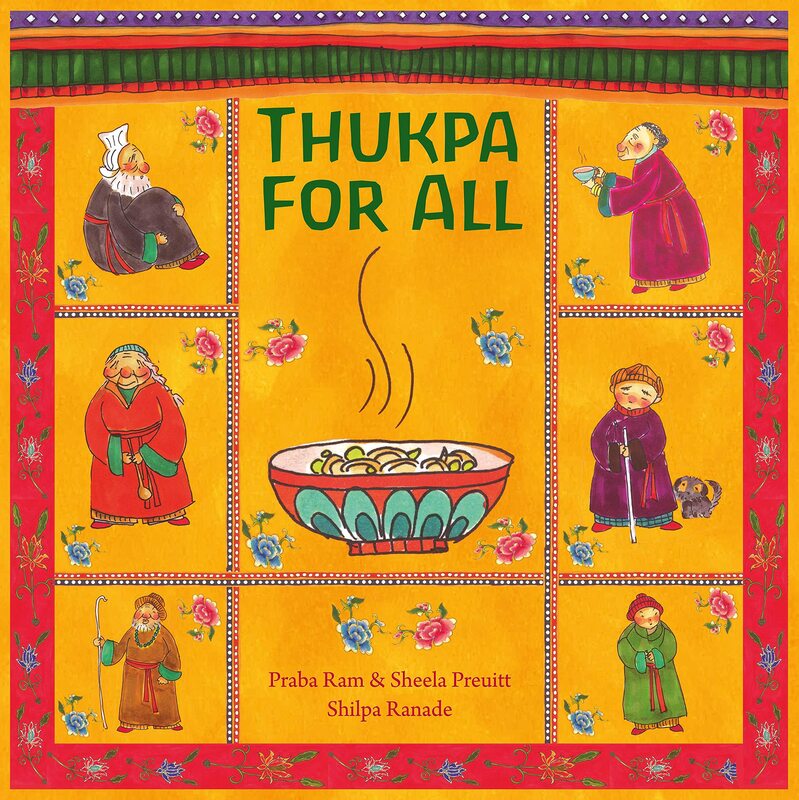

(Book covers are organized by younger-to-older audience gradation.)

(civil, border, global, & cultural)

(civil, border, global, & cultural)

(personal, biographical, cultural, geographical, historical, traditional, philosophical, intergenerational, visual, epistolary)

(accentuating humans’ relationships with the natural world)

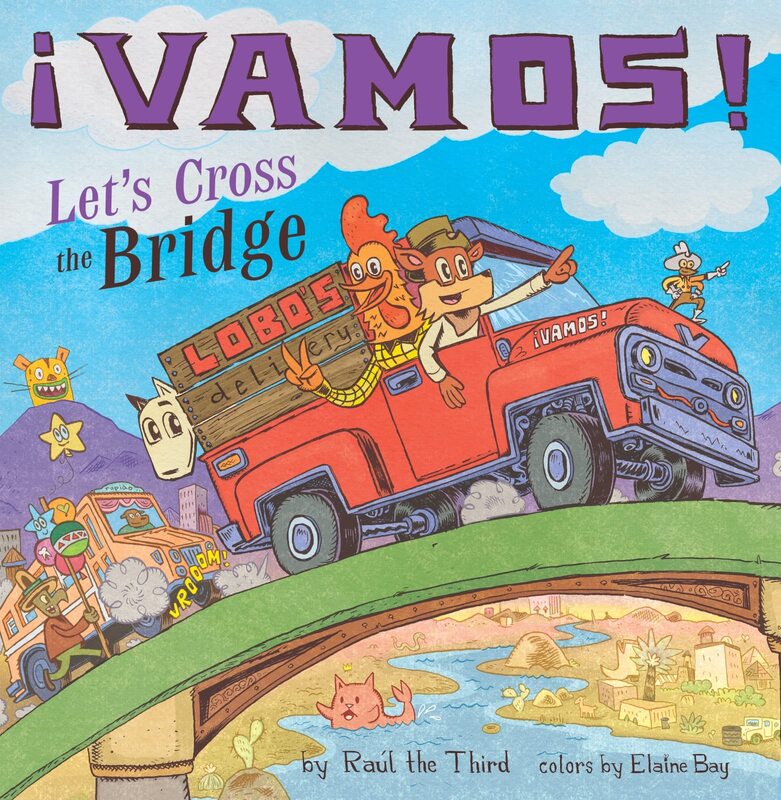

(Playful approaches to familiar topics, how play and curiosity can foster connections and community, and the role of imagination in creating new possibilities and realities, benefits of unexpected journeys)

|

2022 OIB Bookmark & Annotations

|

2021 OIB Bookmark & Annotations

|

2020 OIB Bookmark & Annotations

|

Making Friends and Building Community through Play |

Engaging Math Explorations |

|

|

WWII and Holocaust Survivor Stories |

Family Separations |

|

|

For more information about OIB books and USBBY, please join us in Nashville, Tennessee, March 4-6, 2022 for USBBY’s Regional Conference.

References

Rabbe, C. (2016). “Hello, dear enemy! Picture books for peace and humanity.” Bookbird: A Journal of Children’s LIterature, 54(4), 57-61.

Rabbe, C. & von Merveldt, N. (2018). “Welcome to the new home country Germany: Intercultural projects of the International Youth Library with refugee children and young adults.” Bookbird: A Journal of Children’s LIterature, 56(3), 61-65.

Jennifer M. Graff is an Associate Professor in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia, is a former CLA President and Member for 15+ years.

By Liz Thackeray Nelson & Lauren Aimonette Liang

In our undergraduate children’s literature course we introduce these important awards to begin discussions around evaluation of children’s books. We consider how the criteria might point to ways of evaluating excellence in children’s and young adult literature, and consider the connection of this evaluation to selection of books for use in classrooms, libraries, and other settings.

We also use these award discussions as a way to heighten awareness of the business and marketing side to children’s literature, particularly considering how awards can influence sales, authors’ and illustrators’ careers, publishing trends, and ultimately access to books. Below we briefly describe a reading-reflection sequence and activity that we have found helpful in building undergraduate students’ understanding of the impact of an award.

Reading-Reflection Sequence 1: Read about older children’s book award debates.

We have found that our undergraduate students, in general, have had very little exposure to children’s book awards prior to this class. Many recognize either the Newbery or Caldecott as being a book award for children, but few are aware there are other awards beyond this.

Thus our first step is to introduce students to the idea that there exists many more awards beyond those two. To begin priming students’ thinking about the full range of awards, and their impact, we start by having them read Marc Aronson’s (2001) article, “Slippery Slopes and Proliferating Prizes,” published in The Horn Book Magazine. In addition to reading Aronson’s article, students read the letters to the editor published in the next Horn Book issue that respond to Aronson’s piece as well as Andrea Davis Pinkney’s response article, “Awards that Stand on Solid Ground.”

After students read, we pose Aronson’s position to students: There are too many awards. Students then compose a brief response as to whether or not they agree with the statement and their reasoning. At this point in the discussion, students are often about 50/50 in where they fall on the issue.

Reading-Reflection Sequence 2: Read about the lack of diversity in awards.

To extend Andrea Davis Pinkney’s response article, we then ask students to read two additional articles that begin to address the lack of diversity in books that win the Newbery and Caldecott Medals: Roger Sutton’s (2016) “Last Stop, First Steps” and Megan Dowd Lambert’s (2015) “#WeGotDiverseAwardBooks: Reflections on Awards and Allies.”

We deliberately use these short editorial pieces, both written near the beginning of the #WeNeedDiverseBooks (2014) movement, as they continue students’ understanding of not only these awards, but also focus on the historical lack of diversity in United States’ children’s literature and more recent focus on this problem. Dowd Lambert’s piece mentions the hashtag specifically, which encourages students to visit the WNDB page, where they can learn more. Sutton’s editorial reinforces this with reference to a 1996 discussion, and presentation of numbers of nonwhite authors. It also brings up issues related to book genre and format

After reading these two short pieces, students are again asked to consider the statement: There are too many awards, and then compose a brief response as to whether or not they agree with the statement at this point, and their new reasoning for why they continue in their same opinion, or have now changed their answer. At this point in the activity, with students now having learned a little about the lack of diversity in award winners, we often find that those students who initially thought there were too many awards begin to shift their opinions. And those who disagreed with Aronson from the beginning often feel more justified in their stance that there are not too many awards.

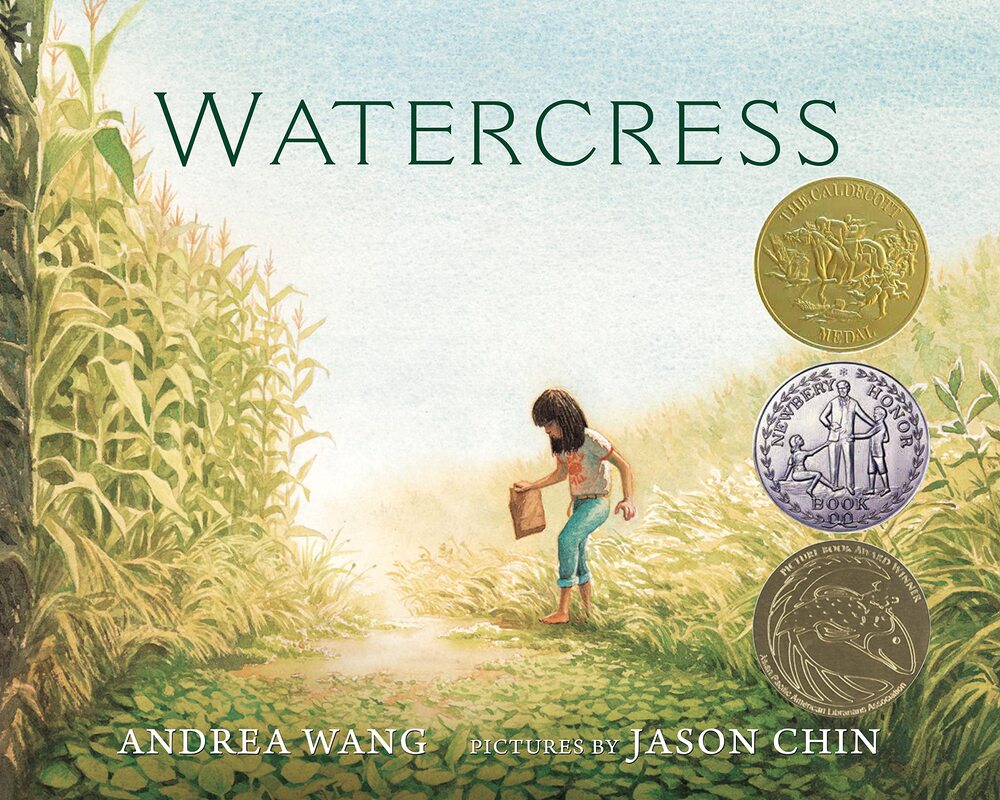

Reading-Reflection Sequence 3: Read about the impact of awards on authors.

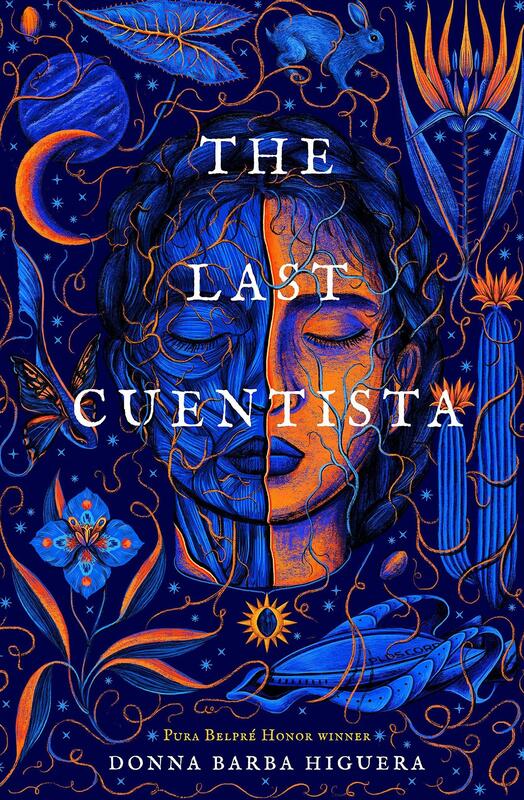

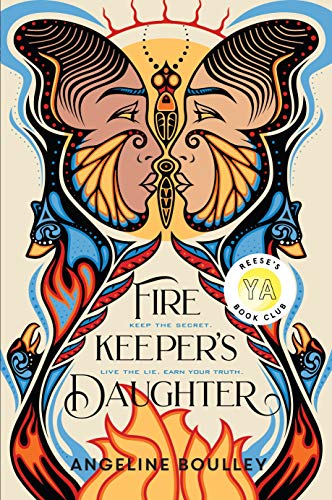

Next, we continue to further students’ understanding by having them learn about the author’s experiences in receiving an award. We seek out the newest reactions; for example, this year, we shared short articles from Publisher’s Weekly about Donna Barba Higuar, Jason Chin, and Andrea Bouley’s experiences when they found out they had won their respective awards. In connection with these readings, we typically ask students to read the short piece “Recognizing Rising Stars” (Aimonette Liang, Reading Today, 2015) that discusses the history and impact of the ILA Children’s and Young Adult Book awards that are designed to honor new authors with extraordinary promise. Quotes from multiple winners highlight the way an award can change the trajectory of an author’s career.

After students consider these additional perspectives, we again ask them to consider the statement: There are too many awards. Once again, they present their opinion and reasoning. We then ask students to explain how their ideas around awards have changed over the course of the set of readings.

Final Activity: Tracking Amazon rankings of award books.

For our final activity to develop students’ understanding of the impact of children’s and young adult book awards, we have students track Amazon book rankings of winning books in the days after the YMA awards have been announced (see our class-compiled results for 2022 below). Students are assigned to an award and asked to find the winning book and honor books on Amazon as soon after the award announcements as possible. They record the sales rank. Students then check 24 hours later on the books’ sales ranks on Amazon. Students are typically shocked at how within hours of the award announcements books are sold out and have substantially higher rankings than they did before; for example, “When I looked earlier today [it] was #2277 and when I looked just now [it] is now #1 in children’s graphic novels. I can’t believe it was that low on the list earlier today and is now sitting at #1!”

This experience helps students understand the impact of awards on the sales of books, and they begin to recognize further how this can affect the sales of future books by the author, and even the publisher in general. (We often add an additional quick check on changes in the sales of the author’s and illustrator’s previous books, or on the sales of that particular genre or format, etc.) Combined with the earlier reflections on readings, the students often begin to bring up concerns about how the award book might affect future children’s book sales, and thus access to both that particular book and others like it.

In their final reflections on awards written after this last activity, nearly all, if not 100%, of the students in the class believe that there is value in having a wide array of awards that can honor diverse authors, illustrators, and books. Some students even go as far to state that there aren’t enough awards!

|

AWARD

|

RANKING/ DATE/ TIME

|

RANKING/ DATE/ TIME

|

RANKING/ DATE/ TIME

|

References:

Aronson, M. (2001). Slippery slopes and proliferating prizes. The Horn Book Magazine, 77(3), 271-278.

Garza de Cortes, O., Bern, A., Watson, J.S., Bishop, R.S., Edwards, C., Blubaugh, P., Caldwell, N., Holton, L., Hamilton, V., Taylor, D., Smith, H., Danielson-Francios, S., Rudd, D., Pinsent, P., Bush, M., & Hurwitz, J., (2001). Letters to the editor. The Horn Book Magazine, 77(5), 500-508.

Lambert, M.D. (2015). #WeGotDiverseeAwardBooks: Reflections on awards and allies. The Horn Book Magazine, 91(4), 101-104.

Liang, L.A. (2015). Recognizing rising stars. Reading Today, 32(6), 34-35.

Lodge, S. (2022, Jan. 25). Donna Barba Higuera’s Newbery win: A dual celebration. Publishers Weekly.

Maughan, S. (2022, Jan. 25). Angeline Boulley’s Printz win: Tears, champagne, and…lawyers? Publishers Weekly.

op de Beck, N. (2022, Jan. 25). Jason Chin’s Caldecott win: ‘Kind of a surreal experience.’ Publishers Weekly.

Pinkney, A.D. (2001). Awards that stand on solid ground. The Horn Book Magazine, 77(5), 535-539.

Sutton, R. (2016). Last stop, first steps. The Horn Book Magazine, 92(4), 11-12.

Lauren Aimonette Liang is Associate Professor at the Department of Educational Psychology of the University of Utah. She is Past President of CLA and co-editor of the CLA Blog.

Authors:

CLA Members

Supporting PreK-12 and university teachers as they share children’s literature with their students in all classroom contexts.

The opinions and ideas posted in the individual entries are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of CLA or the Blog Editors.

Blog Editors

contribute to the blog

If you are a current CLA member and you would like to contribute a post to the CLA Blog, please read the Instructions to Authors and email co-editor Liz Thackeray Nelson with your idea.

Archives

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

October 2023

September 2023

August 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

Categories

All

Activism

Advocacy

African American Literature

Agency

All Grades

American Indian

Antiracism

Art

Asian American

Authors

Award Books

Awards

Back To School

Barbara Kiefer

Biography

Black Culture

Black Freedom Movement

Bonnie Campbell Hill Award

Book Bans

Book Challenges

Book Discussion Guides

Censorship

Chapter Books

Children's Literature

Civil Rights Movement

CLA Auction

CLA Breakfast

CLA Expert Class

Classroom Ideas

Collaboration

Comprehension Strategies

Contemporary Realistic Fiction

COVID

Creativity

Creativity Sponsors

Critical Literacy

Crossover Literature

Cultural Relevance

Culture

Current Events

Digital Literacy

Disciplinary Literacy

Distance Learning

Diverse Books

Diversity

Early Chapter Books

Emergent Bilinguals

Endowment

Family Literacy

First Week Books

First Week Of School

Garden

Global Children’s And Adolescent Literature

Global Children’s And Adolescent Literature

Global Literature

Graduate

Graduate School

Graphic Novel

High School

Historical Fiction

Holocaust

Identity

Illustrators

Indigenous

Indigenous Stories

Innovators

Intercultural Understanding

Intermediate Grades

International Children's Literature

Journal Of Children's Literature

Language Arts

Language Learners

LCBTQ+ Books

Librarians

Literacy Leadership

#MeToo Movement

Middle Grade Literature

Middle Grades

Middle School

Mindfulness

Multiliteracies

Museum

Native Americans

Nature

NCBLA List

NCTE

NCTE 2023

Neurodiversity

Nonfiction Books

Notables

Nurturing Lifelong Readers

Outside

#OwnVoices

Picturebooks

Picture Books

Poetic Picturebooks

Poetry

Preschool

Primary Grades

Primary Sources

Professional Resources

Reading Engagement

Research

Science

Science Fiction

Self-selected Texts

Small Publishers And Imprints

Social Justice

Social Media

Social Studies

Sports Books

STEAM

STEM

Storytelling

Summer Camps

Summer Programs

Teacher

Teaching Reading

Teaching Resources

Teaching Writing

Text Sets

The Arts

Tradition

Translanguaging

Trauma

Tribute

Ukraine

Undergraduate

Using Technology

Verse Novels

Virtual Library

Vivian Yenika-Agbaw Student Conference Grant

Vocabulary

War

#WeNeedDiverseBooks

YA Lit

Young Adult Literature

RSS Feed

RSS Feed