BY RAVEN N. CROMWELL After a four-year hiatus, Marietta College in Marietta, Ohio brought back their summer reading camp in June of 2019. Summer Reading Camp was a three-week, half-day program, sponsored by Marietta College Education Department, designed to assist students in the development of improved reading abilities, oral and written communication skills, and positive attitudes toward reading. Children’s literature and hands-on experiences were the primary instructional tools and camp activities were based around the book The Wild Robot by Peter Brown. Camp was held on campus where students worked in small groups with undergraduate students and local teachers. Priority for camp was given to students who had been recommended for additional literacy instruction by their school. Following our successful return, we decided to revamp our camp to make it even more appealing and helpful to our local families for 2020. We redesigned camp to be full-day in order to provide more reading instruction time and to make the schedule easier to manage for working families. We also expanded our focus to other content areas, renaming the program STREAM camp, which stands for Science, Technology, Reading, Engineering, Art, and Math. This new vision still included high interest books, activities, and reading instruction. However, students would also practice their reading skills and strategies in content-rich texts. Before we could implement STREAM camp, however, we were faced with the global pandemic.

This summer we once again had to place our in-person camp on hold due to the pandemic, and again provide Summer Reading Adventure Packs. Generous contributions from the local community have allowed us to provide 320 packs to local schools for 2021. Additionally, we are listing the selected books and accompanying activities on our website (mcstreamcamp.com) for parents and caregivers who did not receive a pack, but would like to provide this as an enrichment activity for their children. We also created a YouTube channel that features community members reading the books featured in the packs. It is our hope that the reading packs will inspire children to continue to read, explore, and create during the summer in order to be better prepared for their eventual return to the classroom. “The thought of putting these activities together for students is amazing. This is allowing us as a college the opportunity to grow and reach out to the community. It is also helping students continue to grow and learn in a fun way over summer!” —Hannah, a 2021 graduate, who is working on a pet-themed pack for grades K-1 “Did you know that there are robots all around and that you are using aspects of coding to complete everyday tasks? The fourth and fifth-grade students will build their own robot, practice simple coding through giving directions, and even develop their own code with Legos. Through the books and activities the students will get a behind-the-scenes look at the technology that makes up so much of our lives while they develop problem solving skills.” —Elissa, a future graduate, who is working on a STEM-themed pack for grades 4-5 If you are interested in creating your own literacy packs, you should check out the wonderful resources provided by Reading Rockets. They have articles that include why these packs are important and how to create your own. They provide free, downloadable activities and list the companion books you can purchase on your own or check out from your local library. They even have a program called Start with a Book that allows you to explore titles and activities based around several high-interest, content-rich topics. This website also contains helpful hints and instructional videos for caregivers to nurture reading skills and reading motivation in children. We hope that in 2022 STREAM Camp will return to Marietta, improved by the lessons we learned during the pandemic. Resources from Reading Rockets

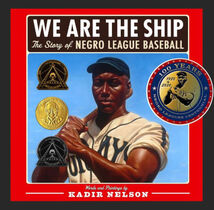

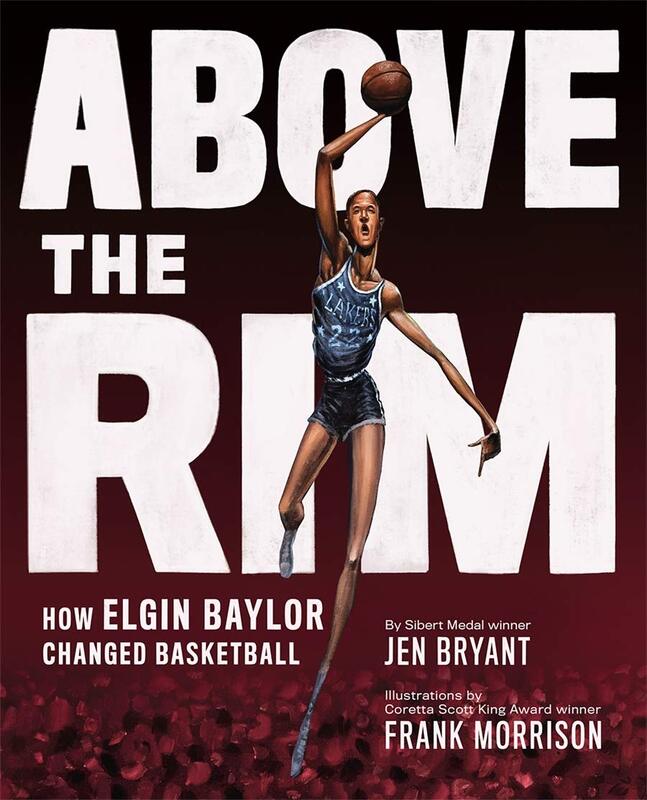

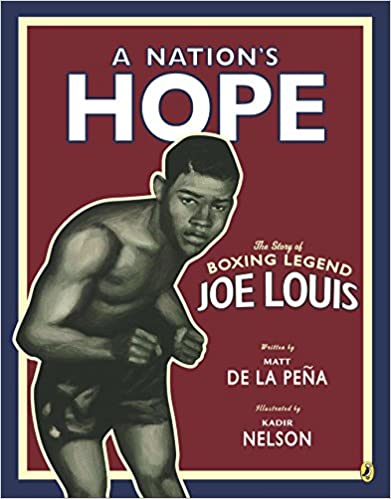

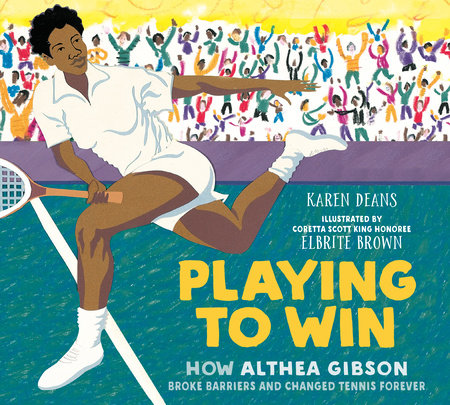

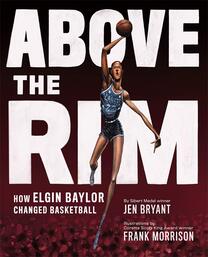

Raven N. Cromwell works in the Education Department at Marietta College in Marietta, Ohio. Her research interests include diverse children’s literature and pre-service education. Raven is a member of CLA’s Ways and Means Committee. By Patricia E. Bandré Sport has the power to change the world. It has the power to inspire. It has the power to unite people in a way that little else does.”  For approximately four weeks this spring, fourth-grade students at Oakdale Elementary in Salina, Kansas read and discussed, We are the Ship: The Story of Negro League Baseball (Nelson, 2008) as part of a language arts unit. Students found the book highly engaging and the art extraordinary. Numerous discussions occurred as students read, wondered, and conducted research in order to learn more about Negro League players and team owners. Ideas in the book sparked a variety of emotions and prompted numerous conversations about how people treated one another then, how they treat one another today, and what it means to break barriers. When the unit concluded, teachers Joy Fox-Jensen and Mary Plott desired to capitalize on students’ enthusiasm for the book and their interest in sports. They wanted to introduce students to other African American athletes who had broken barriers and pursued their dreams. In my role as the district reading instructional specialist, I worked with the teachers to plan and conduct a six-day mini-unit. We chose four books for our study: Above the Rim: How Elgin Baylor Changed Basketball (Bryant, 2020), Playing to Win: The Story of Althea Gibson (Deans, 2007), A Nation’s Hope: The Story of Boxing Legend Joe Louis (de la Peña, 2011), and Wilma Unlimited: How Wilma Rudolph Became the World’s Fastest Woman (Krull, 1996). We intentionally chose to introduce African American men and women who excelled in sports other than baseball and faced barriers in addition to those posed by race; poverty, illness, and physical disabilities provided further challenges for the athletes we selected. We also wanted students to experience a variety of writing styles and different types of illustrations. Finally, we wished to select athletes to whom the students could connect. We wanted them to see how these barrier-breaking athletes valued determination and perseverance, realized the importance of compassion, and understood how seemingly simple actions spoke louder than words. Our goal was to help the fourth graders begin to see how they could become barrier-breakers, too.  Because students demonstrated such a high level of interest in Kadir Nelson’s paintings when reading We are the Ship, we elected to begin the study with a short exploration of book design. I used information from the article Picturebooks as Aesthetic Objects (Sipe, 2001) to help frame our conversations. We are the Ship (Nelson, 2008), along with two classic picturebooks, Where the Wild Things Are (Sendak, 1963) and The Little House (Burton, 1942), served as models. After reading the two picturebooks aloud, we took a focused look at all three books. As part of our discussion, I prompted students to consider how the size and shape of a book might add to its meaning. Students contemplated the image on the dust jacket and cover of each book – were these images the same or different? Why? They looked closely at the endpapers and wondered about the significance of the colors and the images, if there were any. We considered the color palette each artist used and discussed how those colors suited the text and made them feel. Students noticed the different points of view Nelson employed in We are the Ship; individual players appeared to be larger than life, but in the team paintings, each member seemed equally significant. Students greatly admired Nelson’s full-bleed art, but also found the way Sendak (1963) placed frames around his illustrations in Where the Wild Things Are to be intriguing. Students were quick to notice how the size of the frames changed, disappeared, and reappeared as we watched the main character, Max, journey in and out of his imaginary world. Ultimately, this exploration created a heightened sense of awareness and resulted in careful observations, thoughtful questions, and insightful responses about the other books we read.  Over the next four sessions, students interacted with a new book each day. Each initial reading was conducted as a read-aloud or a combination of listening and partner reading. I purposely did not stop to talk about the book during its first reading. Rather, I wanted students to take in the language and art on their own in order to develop a first draft understanding (Barnhouse and Vinton, 2012). Following this process allowed them to come to their own conclusions about the athletes and the barriers faced without the influence of their peers. Instead of talking, students took two sticky notes and recorded one thing they noticed about the book and one fact they learned during the first read. Students shared their “Notice and Learn” notes with a shoulder partner and posted them for others to read. Next, we dove back into each book and revisited specific passages in order to explore the way the authors used language to provide clues as to the personality of each athlete. An organizer modeled after the Reading with Attitude protocol (Buehl, 2014) assisted to facilitate our conversations. As students reread certain passages from each book, they contemplated the athlete’s and author’s emotions and shared how the text made them feel as the reader. Discussions ensued about the language in the text and how it prompted them to infer the presence of these emotions. Additionally, students made specific references to the art in each book and how it affected their response. As students met each new athlete, the comments they shared made it clear that they realized the athletes were different from one another, but connected by common threads

References

Barnhouse, D., & Vinton, V. (2012). What readers really do: Teaching the process of meaning making. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Buehl, D. (2014). Classroom strategies for interactive learning, (4th ed.). International Reading Association: Newark, DE. Sipe, L. R. (2001). Picturebooks as aesthetic objects. Literacy Teaching and Learning, 6(1), 23-42. Children’s Books

Bryant, J. (2020). Above the rim: How Elgin Baylor changed basketball. Illus. by F. Morrison. Abrams Books for Young Readers: New York, NY. Burton, V. L. (1942). The little house. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. Deans, K. (2007). Playing to win: The story of Althea Gibson. Illus. by E. Brown. Holiday House: New York, NY. de la Peña, M. (2011). A nation’s hope: The story of boxing legend Joe Louis. Illus. by K. Nelson. Dial Books for Young Readers: New York, NY. Krull, K. (1996). Wilma unlimited: How Wilma Rudolph became the world’s fastest woman. Illus. by D. Diaz. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston, MA. Sendak, M. (1963). Where the wild things are. HarperCollins Publishers: New York, NY. Patricia E. Bandré, Ph.D., is the reading instructional specialist for USD 305 Public Schools, Salina, KS and serves as treasurer for CLA. Joy Fox-Jensen and Mary Plott are fourth grade teachers at Oakdale Elementary School, USD 305 Public Schools, Salina, KS. We wish to thank the Salina Education Foundation for funding this project. It’s a Slam Dunk! Aiming High with Jen Bryant’s Above the Rim: How Elgin Baylor Changed Basketball5/11/2021

By Donna Sabis-Burns and Amina Chaudhri, on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse

Please visit The Biography Clearinghouse for an interview with Jen Bryant and a range of critical teaching and learning experiences to use with Above the Rim. Highlighted here are a few teaching ideas inspired by Above the Rim. The full book entry is available at the Biography Clearinghouse. Literary and Figurative Language Jen Bryant wrote Above the Rim in prose verse - a form of writing that does not use a rhyme scheme or rhythm but is formatted to look distinctive on the page, and makes use of word and line spacing to create an effect. The reader must carefully follow the punctuation in order to read prose verse fluently rather than pausing at the end of each line. This form also allows the writer to isolate particular sentences, placing them on lines of their own, which can serve to call attention to them. Bryant does a beautiful job in capturing the rich emotion of Elgin Baylor through careful word choice and line spacing.

Analyzing Character In her interview, Jen Bryant frames her work as a writer with a quote from the poet, Nikki Giovanni: "Writers don't write from experience, they write from empathy." She adds that she hopes her readers will empathize with Elgin Baylor and understand him in the context of his environment. Above the Rim characterizes Elgin as persistent, humble, brave, and more and as such, can be used to teach about character traits using text evidence.

Donna Sabis-Burns, Ph.D., an enrolled citizen of the Upper Mohawk-Turtle Clan, is a Group Leader in the Office of Indian Education at the U.S. Department of Education* in Washington, D.C. She is a Board Member (2020-2022) with the Children's Literature Assembly, Co-Chair of the 2021 CLA Breakfast meeting (NCTE), and Co-Chair of the Diversity, Equity and Inclusivity Committee at CLA.

Amina Chaudhri is an associate professor at Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago, where she teaches courses in children's literature, literacy, and social studies. She is a reviewer for Booklist and a former committee member of NCTE's Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction for Children. *The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the positions or policies of the U.S. Department of Education. No official endorsement by the U.S. Department of Education of any product, commodity, service, or enterprise mentioned herein is intended or should be inferred. BY EUN YOUNG YEOM

Using YAL to include emergent bilinguals’ voices

Reading young adult literature (YAL) can be very beneficial for secondary-level students and can operate as a powerful context for discussing complex social issues relevant to students’ lives and current society. Reading and discussing YAL can expand students’ horizons and their conceptions of themselves. The benefits of reading and discussing YAL could also be applied to English learning emergent bilingual adolescents. Recent studies show that leveraging emergent bilinguals’ heritage languages as a scaffold can support English development. However, few educators and researchers discuss how secondary-level emergent bilinguals make sense of the world through reading and discussing YAL written in English, how responding to YAL can be a medium to amplify their voices, and how their heritage languages could be a steppingstone for them to immerse themselves into YAL texts. In many U.S. classrooms that are often dominated by standard English, emergent bilingual adolescents’ perspectives toward YAL and their conceptions of the world can easily be dismissed. One core reason could be that emergent bilinguals’ written and oral utterances, often expressed through developing English mixed with their heritage languages, might look different from standard English expression. However, emergent bilinguals make sense of the world through intermingling their heritage languages and English, a process called translanguaging. Using heritage languages can serve as a bridge for emergent bilinguals to make meaning of YAL texts written in English because translanguaging is a natural way in which bilinguals engage with the world. Through this lens, emergent bilinguals are seen as capable meaning makers with diverse cultural and linguistic repertoires, not as English learners with limited English proficiency who cannot form proper English sentences. Classroom language policy matters Taking advantage of their heritage languages for discussing YAL can open doors for emergent bilingual students to express their opinions easily, and to access their lived experiences and cultural values in relation to the YAL texts they are reading and discussing. For secondary ELA classrooms where many YAL texts are incorporated, allowing emergent bilingual students use of their heritage languages could be a first step toward including more of their voices in discussions. For written responses, opening translanguaging spaces for intermixing heritage languages and English could be another way to honor bilingual students' cultural and linguistic resources and expand their expression options. Ultimately, teachers’ efforts to create a more linguistically inclusive classroom environment can support emergent bilingual students’ active involvement in YAL reading and discussions and can enrich the breadth of ideas and interpretations made available to the classroom community. Teachers’ modeling of blending two languages to make meaning could also reap benefits.

Integrating culturally relevant YAL also matters

In addition to efforts toward linguistic inclusiveness through translanguaging practices, incorporating culturally relevant YAL is equally important. If emergent bilingual students have to sit in a classroom reading a novel written in a second language they have started learning, text analysis will take tremendous energy. If they also have to discuss the novel in the foreign language, they may not be able to fully express their thoughts and feelings, even when formulating insightful ideas in their heads. To make matters worse, if the novel is irrelevant to their lives and cultures, the hardship comes in a combo plate. Incorporating YAL texts that are relevant to emergent bilinguals’ lives is one of the choices teachers can make for emergent bilinguals to feel more included by seeing themselves in the stories they are reading. Emergent bilingual adolescents, who may feel marginalized due to languages, race, and their status as immigrants or refugees, need school to be a space where they feel valued and validated. They are an important part of the colorful fabric of U.S. classrooms, which have increasingly become linguistically diverse. By respecting emergent bilingual adolescents’ bilingual repertoires and honoring their cultural identities through culturally relevant YAL, ELA classrooms can become a welcoming, empowering space for emergent bilingual adolescents to express their feelings, thoughts, and perspectives. RESOURCES

Translanguaging Guides | CUNY-NYSIEB Recommended sites for finding culturally relevant YAL for emergent bilingual adolescents Immigration and refugee experiences:

Asian immigrant experiences:

Latinx immigrant experiences African immigrant experiences: YAL about immigrants from the Middle East or Middle Eastern characters:

Eun Young Yeom was an in-service middle/high school English teacher in South Korea for 12 years, and is a doctoral student in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia. Her research revolves around transnational emergent bilinguals’ language practices and their responses to young adult literature.

|

Authors:

|

CLA

About CLA

|

Journal of Children's Literature

Write for JCL

|

ResourcesCLA-sponsored NCTE Position Statements

|

Members-Only Content

CLA Video Library

|

© COPYRIGHT 2018.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed