by Kate Narita, introduction by Melissa Stewart

In February, CLA members Mary Ann Cappiello, Professor of Language and Literacy at Lesley University and Xenia Hadjioannou, Associate Professor of Language and Literacy Education at Penn State University, sent a letter signed by more than 500 educators to The New York Times asking the paper to add children's nonfiction bestseller lists to parallel the current fiction-focused lists.

The letter was also published on more than 20 blogs that serve the children's literature community--including this one—and amplified on social media as part of the #KidsLoveNonfiction campaign. (To date, more than 2,100 people have signed it.) A few weeks later, The New York Times responded, saying it had no current plans to add nonfiction lists at this time. Many people were disappointed by this decision, including fourth-grade teacher and CLA member Kate Narita, who has written the following essay, bravely sharing how the petition changed her thinking. -- Melissa Strewart Shattering My Implicit Bias Against Nonfiction by Kate Narita

Then, in January, my son mentioned a book he had read, Infinite Powers: How Calculus Reveals the Secrets of the Universe by Steven Strogatz. “Oh,” I said. “Sounds interesting. Did you read it for your calculus class?” “Yes,” he said. “And I really enjoyed it.” Did his statement about enjoying a book wake me up to my implicit bias? No. But I did feel a shift inside me. I was pleasantly surprised and excited because I love talking about books. If he had read something and was excited about it, I could read it and discuss it with him, even if he had only read it because it was a class assignment. Here was a way I could deepen my relationship with him as an adult. Even if it was just a one-time occurrence. I asked if I could read the book when he was done, and he brought it home the next time he visited. Fast forward to February break. As my husband and I were packing for a trip to Maui to celebrate our 25th wedding anniversary, he spotted Infinite Powers in the pile of books I was sorting through on our ottoman and picked it up. “What’s this?” he asked. When I explained, he asked if he could take it to Hawaii, and I nodded. I hadn’t read it yet because, to be honest, reading a whole book about calculus felt too daunting. Instead, I packed and read three books from Kate Messner’s History Smashers series and Rukhsanna Guidroz’s Samira Surfs. I also spotted a copy of Kristin Hannah’s Fly Away in our condo. Since I had watched Hannah’s Firefly Lane on Netflix and was listening to The Four Winds on Libby, I couldn’t resist picking up Fly Away, and I devoured it in a day. As my husband and I sat side-by-side reading on the beach, we talked about Infinite Powers. He told me that while he was enjoying the book, the author gave way too much credit to calculus and not nearly enough to physics. He was kind of cranky about it. Actually, he was truly irritated. I was surprised that he was having an emotional response to the book, a nonfiction book. It had stirred up passion inside him, even though it wasn’t a novel. Did his passion wake me up to my implicit bias? Not yet. But I did feel another shift. He was expressing emotion about a book, and I was listening. In the past, it had almost always been me expressing emotion about a novel and him listening.  In our almost thirty-year relationship, I could only think of one other time when he had emoted about a book. It was Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! by Richard Feynman, which I read because he had read it multiple times and was so excited about it. When we got back home, I spotted this petition (which you can still sign) on Twitter. Two professors of literacy, Mary Ann Cappiello and Xenia Hadjioannou, had written a letter asking The New York Times to add three children’s nonfiction bestseller lists—one for picture books, one for middle grade, and one for young adults. I signed it because, of course, I fully supported nonfiction writers and readers! A couple of weeks later, I saw on Facebook that, even though more than 2,000 people had signed the petition, The New York Times had refused to add children’s nonfiction bestseller lists. After a full day of teaching, I was tired, and reading this unfortunate news made me angry. I looked up from my phone. Across the room, my younger son, who was home on spring break, was reading The Elegant Universe: Superstrings, Hidden Dimensions, and the Quest for the Ultimate Theory by Brian Greene for fun because he had liked Infinite Powers so much and wanted to keep reading and learning. Next to him, my husband was reading an article about the Green Bay Packers on the internet.  In that instant, a lightbulb clicked on in my mind, and an awareness of my implicit bias washed over me like a tidal wave. My husband and younger son are readers. They have always been readers. I just didn’t realize it because narratives and fiction aren’t their jam. But give them nonfiction on topics they find fascinating—math, physics, sports—and they’re all in. They’re curious people who read to learn. They want to know about the world, how it works, and their place in it. The decisionmakers at The New York Times seem to have their own implicit bias against children’s nonfiction, and as long as they do not include lists highlighting these books, they’re failing to acknowledge the 42 percent of our youth who crave true texts. They’re also failing to open the eyes of adults who raise those kids, thinking they’re not readers. Maybe we should petition The Wall Street Journal next.

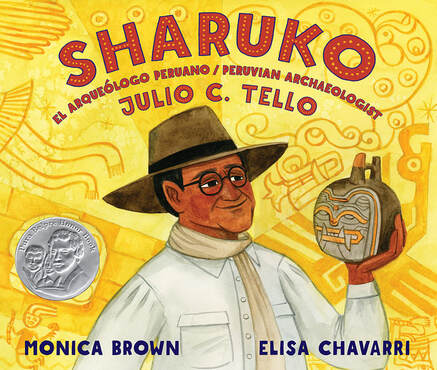

By Amina Chaudhri and Julie Waugh, on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse One of the most profoundly devastating schemes of the colonial project was to erase Indigenous knowledge: religious, intellectual, social, cultural, aesthetic, scientific. In the Afterword of Sharuko, Monica Brown extends readers’ knowledge of the importance of Julio C. Tello’s work as an archaeologist in undoing the damage of colonial erasure. He spent his life raising awareness about Indigenous Peruvian ways of knowing, as evidenced by his research. Julio C. Tello was Indigenous and spoke Quechua, so his investment in countering the dominant narrative was personal as well as professional. Today, he is a celebrated figure in Peru, and through Sharuko, young readers can come to value his accomplishments as well. This entry of The Biography Clearinghouse offers a variety of teaching and learning experiences to use with Sharuko: el Arqueólogo Peruano/Peruvian Archaeologist, a bilingual biography of Julio C. Tello, written by Monica Brown, and illustrated by Elisa Chavarri. In addition to a recorded interview with the author in which she discusses her research process and the craft of creating picturebook biographies, we include suggestions for learning about Peruvian textiles, the Quechua language, and variations on the trait of bravery. Below are two ideas inspired by Sharuko. Connecting the Past and the Present Sharuko is the biography of a man who lived from 1880 - 1947, yet his work as an archeologist and conservationist is relevant today. His legacy includes the Museum of Anthropology, in Lima Peru, that houses the artifacts he discovered and wrote about. His research spotlights the accomplishments of Indigenous Peruvians and tells the story of Peru’s past that colonialism tried to erase. In her interview, Monica Brown tells us about a “magic moment” in the process of creating this book, in which she imagined a Quechua word - sharuko- emblazoned across the front as its title. In this way she continues Tello’s legacy, using her privilege as an established writer to highlight the Quechua language and the contributions Tello, an Indigenous scholar, made to the world. Begin by reading Sharuko aloud with students, inviting them to note the chronology of his life, from boy to researcher, the people who supported him along the way, and his connections to history as depicted in the text and images. In analyzing this biography, teachers might scaffold students’ understandings of:

Thinking Like an Archeologist Sharing Sharuko can provide a similar introduction to the complexities and exciting puzzles that define the field of archeology. Archeology is about telling the human story. Invite your students to act as archeologists, researching, writing, and considering the different perspectives that inform archeological work. Teachers can find teaching ideas related to archeology on the website of The Society of American Archeology. The teaching and learning suggestions below are designed for teachers to plan experiences that involve thinking like an archeologist:

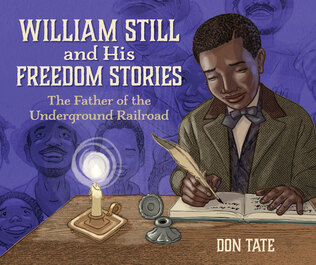

For more teaching and learning suggestions, visit the complete entry on Sharuko, on The Biography Clearinghouse website. Amina Chaudhri is an associate professor at Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago, where she teaches courses in children's literature, literacy, and social studies. She is a reviewer for Booklist and a former committee member of NCTE's Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction for Children. Julie Waugh shares a 4th grade teaching position at Zaharis Elementary in Mesa, AZ and serves as an Inquiry Coach for Mesa Public Schools. She delights in the company of children surrounded and inspired by books. A longtime member of NCTE, and an enthusiastic newer member of CLA, Julie is a former committee member of NCTE's Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction for Children. BY AMINA CHAUDHRI AND MARY ANN CAPPIELLO, ON BEHALF OF THE BIOGRAPHY CLEARINGHOUSE “William Still’s records, and the stories he preserved, reunited families torn apart by slavery. Because that’s what stories can do. Protest injustice. Sooth. Teach. Inspire. Connect. Stories save lives.” - Don Tate, from William Still and His Freedom Stories: The Father of the Underground Railroad  As 2021 begins, we want to acknowledge the continued need to show young people that Black Lives Matter. Part of that responsibility is shifting our curriculum away from a white-centered view of U.S. history and towards a more multifaceted exploration of all of the communities that have lived on this land from prehistory to today. Don Tate’s picturebook biography William Still and His Freedom Stories: The Father of the Underground Railroad, this month’s featured text on The Biography Clearinghouse, is an important text to help make this change in elementary and middle school classrooms. William Still and his Freedom Stories is one of several recent publications that highlights the role of African Americans in the freedom struggle, countering the narrative that freedom from slavery depended on the actions of whites. A precise, linear narrative takes readers through significant events that shaped William Still’s understanding of the world and his role in making it better for African Americans. Readers follow Still from childhood to adulthood, bearing witness to his desire to learn, the grueling labor he endured to earn a living, and eventually, the risks he took to secure freedom for enslaved people and his post-Civil War activism to fight segregation. This deeply-researched and powerfully-illustrated book has layers of curricular potential: as a read aloud, as a mentor text for literacy skill development, as a model of the genre of biography, as an important piece of history, and much more. Operating within the Investigate, Explore, and Create Model of the Biography Clearinghouse, we designed teaching ideas geared toward literacy and content area learning as well as opportunities for socio-emotional learning and strengthening community connections using William Still and His Freedom Stories. Featured here are two teaching ideas inspired by William Still and His Freedom Stories. The first engages students deeply with the text itself - its form and content, and the second extends learning beyond this picturebook to explore multiple sources for inquiry and research.

Advocating for and Learning from 19th Century Black-Authored Texts For far too long, too many students in the U.S. have been taught a white-centered modern history that avoids a close examination of imperialism and the legacy of Europe’s colonial reach. The brutal history of the global slave trade of the 17th - 19th centuries has been marginalized as have the many stories of Black agency, resistance, and liberation. As a consequence, young people - and many adults - have limited knowledge of that history. We need this to change. William Still and His Freedom Stories is one text that helps to make that change. In this teaching idea for middle school students, we leverage the conversations that this book can open with more in-depth research writings of 19th century activists such as William Still and 19th century Black journalists.

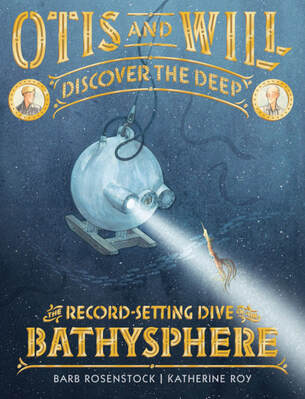

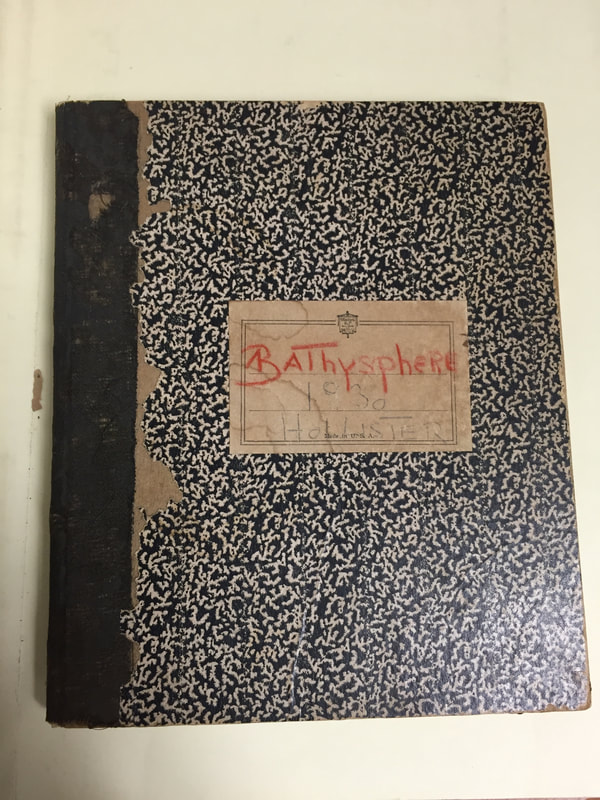

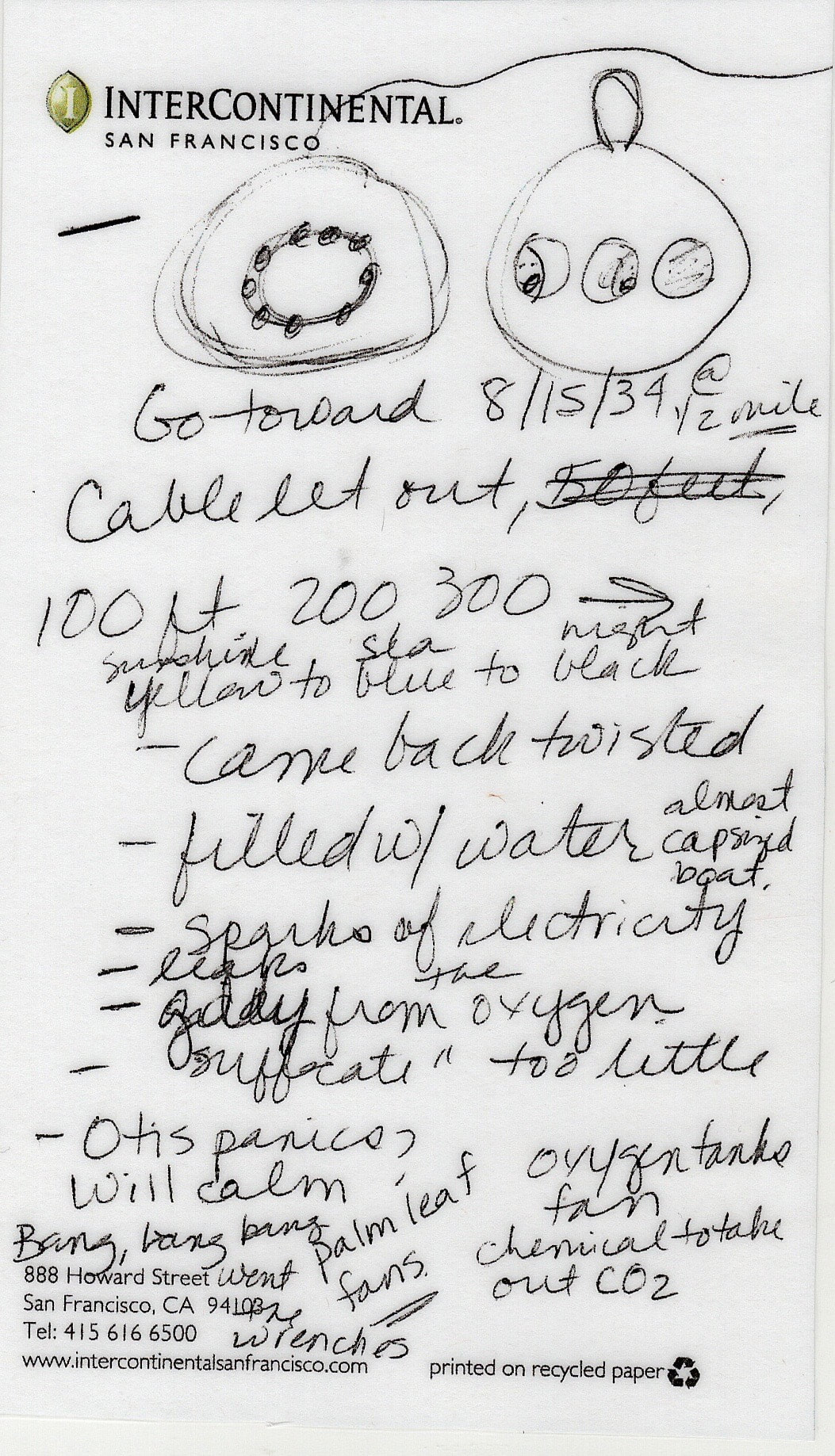

Amina Chaudhri is an Associate Professor of Teacher Education at Northeastern Illinois University. She is a reviewer for Booklist and a regular contributor to Book Links. Mary Ann Cappiello teaches courses in children’s literature and literacy methods at Lesley University, blogs about teaching with children’s literature at The Classroom Bookshelf, a School Library Journal blog, and is a former chair of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8. BY ERIKA THULIN DAWES & MARY ANN CAPPIELLO on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse  Over the last nine months, many of us feel as if we have had a front row seat to a global scientific conversation. Since the first news reports of a new virus in Wuhan, China in early January, our knowledge and understanding of COVID-19 has been steadily developing. For the first time in history, scientists around the world are working concurrently and urgently on the same challenge: creating viable vaccines and treatments for COVID-19. Early on, scientists did not believe the virus spread from animals to humans. For months, scientists debated whether or not the virus gets transmitted from both droplets and aerosols. Various treatments for the virus have been developed, undergone clinical trials, and been either adopted or rejected. We’ve heard news reports about peer-reviewed publications making announcements about new understandings of the virus. None of the progress that we have made on fighting COVID-19 would be possible without scientists collaborating around the world, sharing information with one another and the public. The world is doing its best to keep its people safe, through collaboration and the scientific process. You can’t look at a newspaper, glance at your phone, or watch the evening news without hearing the latest information that scientists have hypothesized, tested, or concluded. For young people - indeed, for all of us - this overload of information is overwhelming. It’s also fascinating. The amount of information we are receiving is staggering. We are watching “science” happen in real time - the processes and the methods, the dead ends and the real results. How do we make these processes and methods visible in elementary and middle school? What are some of the ways children’s literature can provide our young people with a window into the scientific process so they can better understand what thousands of grown-ups around the world are doing to try and beat this virus? One small way is to explore the scientific process and the collaboration made visible in the picturebook Otis and Will Discover the Deep, written by Barb Rosenstock and illustrated by Katherine Roy. Operating within the Investigate, Explore, and Create Model of the Biography Clearinghouse, we designed teaching ideas geared toward literacy and content area learning as well as opportunities for socio-emotional learning and strengthening community connections.

CREATE with Otis and Will Discover the Deep. Featured here is one of the teaching ideas inspired by Otis and Will Discover the Deep: Unlikely Collaborators: Researching Collaboration When we interviewed Barb Rosenstock about researching and writing, Otis and Will Discover the Deep, we were so surprised to discover that Otis and Will didn’t like each other! Given the incredible teamwork displayed in the book, we were a bit dumbfounded. But as Rosenstock points out, getting a job done does not always require that people like each other. It’s about the commitment to the task at hand and the sharing of talents and information to make it happen. How does teamwork and collaboration happen? Why is it so important?

By investigating biographers’ research and writing processes and connecting people and historical events to our modern lives, we hope to motivate change in how readers engage with biographies, each other, and the larger world. To see more classroom possibilities and helpful resources connected to Will and Otis Discover the Deep: The Record Setting Dive of the Bathysphere, visit the Will and Otis entry at the Biography Clearinghouse. Additionally, we’d love to hear how these interviews and ideas inspired you. Email us at [email protected] with your connections, creations, questions, or comment below if you’re reading this on Twitter or Facebook. If you are interested in receiving notifications when new content is added to the Biography Clearinghouse, you can sign up for new content notices on our website. Erika Thulin Dawes is Professor of Language and Literacy at Lesley University where she teaches courses in children’s literature and early childhood literacy. She blogs about teaching with children’s literature at The Classroom Bookshelf, a School Library Journal blog, and is a former chair of NCTE’s Charlotte Huck Award for Outstanding Fiction for Children. Mary Ann Cappiello teaches courses in children’s literature and literacy methods at Lesley University, blogs about teaching with children’s literature at The Classroom Bookshelf, a School Library Journal blog, and is a former chair of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8. |

Authors:

|

CLA

About CLA

|

Journal of Children's Literature

Write for JCL

|

ResourcesCLA-sponsored NCTE Position Statements

|

Members-Only Content

CLA Video Library

|

© COPYRIGHT 2018.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed