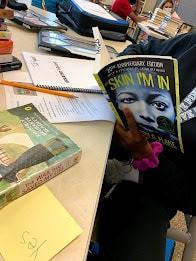

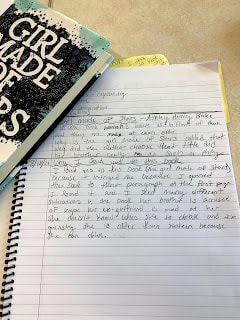

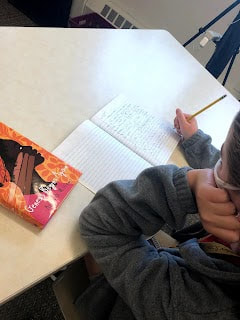

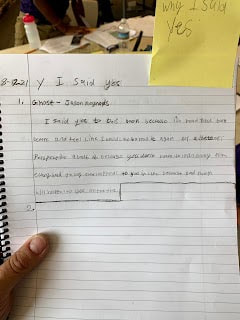

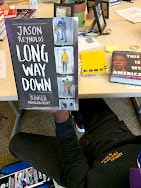

By Debbie Myers The amount of time readers spend engaged with self-selected text matters. Kylene Beers and Bob Probst, authors of many professional development books such as Disrupting Thinking: Why How We Read Matters (2017), argue that self-selected reading is one way to increase reading engagement. In Disrupting Thinking (2017), Beers and Probst explain a study conducted by Anderson and colleagues (1988). This study demonstrates the impact of time spent reading on reading achievement. One measure Anderson et al. use is the total number of words a student encounters based on the time they spend reading outside of school and their reading rate. The results of the study indicated that fifth graders who were in the 98th percentile read 65 minutes a day outside of school and encountered approximately 4.3 million words each year. In contrast, students in the 70th percentile read for only 10 minutes a day, decreasing the number of words they encountered to 622,000. Students in the 50th percentile read for only 5 minutes a day and encountered only about 282,000 words. Finally, students in the 30th percentile read for less than 2 minutes each day and encountered only 106,000 words each year. The disparities between the amount of time read, the projected number of words encountered, and reading achievement was striking. Anderson and colleagues concluded that teachers can have a large influence on how much time students spend reading outside of school and suggested that teachers work to connect readers with high-interest texts at an appropriate reading level. Since the amount of time readers spend engaged with self-selected texts clearly matters, our job as teachers is to work hard to get those self-selected texts into our students’ hands. I use Book Tastings to introduce students to a wide variety of books. This post will describe what a Book Tasting is, how to host one, and some of the results of Book Tastings I have done with my students. What is a Book Tasting? Similar to a wine tasting or food tasting event, Book Tastings are an event where readers sample or “taste” a selection of books. This activity encourages readers to sample a large selection of books in a fairly short period of time as a way to help them find a book they are interested in reading. Book Tastings are great events to hold at the beginning of the school year, the beginning of a new quarter, or any time you feel like your students need some to sample some new reading materials.  How do I Host a Book Tasting? To host a Book Tasting event, teachers should collect a variety of high-interest books across a range of genres. You can host the tasting in your own classroom or even ask the school librarian to pull some books for students to taste in the library. Once you have collected your texts, create areas in the classroom to display the texts so that the covers of all of the texts are visible. You may decide to categorize the texts by genre in different areas of the room so that there is a section for fantasy books, a section for historical fiction, etc. Pass out three sticky notes to each student. Instruct students to write "yes," "no," and "maybe" on each post-it note and put them on their desks. Students will use these to categorize the books they taste into three piles. Once readers have their sticky notes ready to go, the teacher sets the timer and gives them 90 seconds to walk around the room, gathering books for their book tasting stacks. Readers select ten books to taste. Allow students lots of time to taste their book selections. Ideally, readers will taste books from all genres, but it is more important to make book tasting a positive experience. Therefore, I never ask students to put books back; rather, I simply remind them that I hope they will expand their reading horizons this year by engaging with different types of books and books that showcase many different perspectives. So if students have an entire stack of fantasy books, I offer a few more books to taste from other genres to help them consider some additional possibilities. Encourage readers to sample their books in multiple ways and in ways that feel natural for them. I suggest that readers examine the front and back covers of the book and read at least 3-5 pages of the book before making a determination. I also suggest that they read the back cover or inside flap if that is something they like to do. After readers taste each book, they categorize them into three piles: a yes pile, a no pile, and a maybe pile. After categorizing each book, readers go back to their maybe piles and sample the books again to make a yes or no determination. If readers have more than one book in their yes piles, they decide which book they will read first and add the other yes titles to their “to be read” (TBR) lists in their reading journals.  Why Use Book Tastings? Oftentimes, students arrive in class without knowing who they are as readers because previous teachers have been the ones selecting the books they read. Because students often are not afforded opportunities to select their own reading materials, they often have a negative attitude toward reading. At the beginning of each school year, I ask my students to rate how much they like reading on a scale of 0 to 5, where 0 is “I don’t like reading yet” and 5 is “I love reading so much that I need to read ALL the books right now.” During the 2020-2021 school year, I began the year with only 22% of my students selecting a 3 or higher. When I asked my students to rate how much they like reading again at the end of the year, that number had increased to 92%. Assisting my students in discovering books that were interesting to them not only increased the amount of time they spent reading, but also increased their attitude toward and enjoyment of reading. This year, we are off to an even more promising start. When I asked my students to rate how much they enjoy reading at the beginning of the 2021-2022 school year, 63% of students selected a 3 or higher (see image on the right). These results give me hope that with the use of Book Tastings throughout the year, I will reach my end goal of 100% of students rating their enjoyment of reading at a 3 or higher. My Fall 2021-2022 Book Tasting On the first Book Tasting day this school year, the room was dead silent as readers tasted their books. Some students chose to take notes, while others did not. Once each student had at least three or four books in their YES stacks, I asked them to make the most important decision a reader can possibly make: decide which book to read first. After readers made their decision, I asked them to journal about the book they chose and why they had said yes to the books they selected. In the end, each reader had a self-selected book and most had already started their To-Be-Read (TBR) stacks with some pretty fantastic reads! Getting self-selected books into the hands of my readers helped students feel motivated and inspired to read - and that's exactly what I needed to initiate a positive shift in their perception of reading. On Day 5, the last day of our first week of school for the 2021-2022 school year, I gathered the last bit of data I needed, and, based on what I found, I am pretty sure my end goal thinking is on the right track. I am thrilled to share that at the end of our first week of school, my readers - as a collective group of 59 students - had read 4,895 pages of self-selected text - and many had already finished more than one book. In fact, some students had finished three or more books, and the enthusiastic chatter and sharing of books and journal entries during 'care to share' journal time told me we were off to a phenomenal start! References Anderson, R. C., Wilson, P. T., & Fielding, L. G. (1988). Growth in reading and how children spend their time outside of school. Reading Research Quarterly, 23(3), 285–303. Beers, K., & Probst, R.E. (2017). Disrupting thinking: Why how we read matters. New York: Scholastic. Debbie Myers is an 8th Grade Reading Teacher at Milton Hershey School and a member of CLA. She is also the co-planner of nErD Camp PA. BY JEANNE GILLIAM FAIN ON BEHALF OF THE NCBLA 2021 COMMITTEEThe NCBLA 2021 committee has the following charge as a committee:

The charge of the seven-member national committee is to select 30 books that best exemplify the criteria established for the Notables Award. Books considered for this annual list are works of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry written for children, grades K-8. The books selected for the list must meet the following criteria: 1. be published the year preceding the award year (i.e. books published in 2021 are considered for the 2020 list); 2. have an appealing format; 3. be of enduring quality; 4. meet generally accepted criteria of quality for the genre in which they are written; 5. meet one or more of the following criteria:

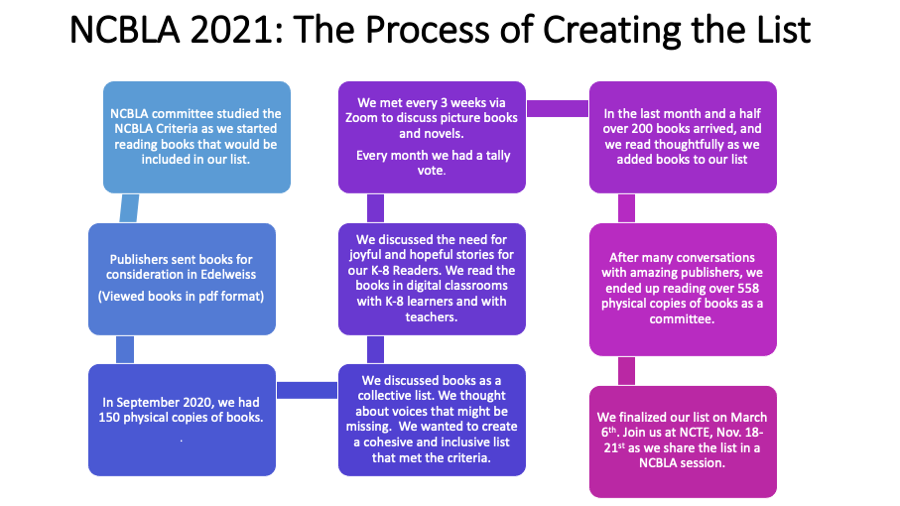

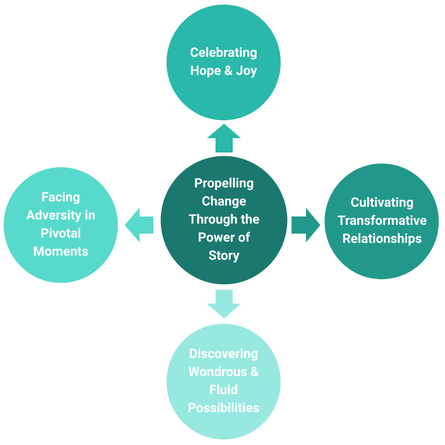

Books transport us into new places and sometimes take us out of the craziness of the world. This was one of those years where we experienced unexpected challenges. I led this committee as we navigated some of the real challenges of the pandemic. To be perfectly honest, in September when we didn’t have the normal number of books, I panicked. I am truly thankful for this thoughtful committee that continually encouraged me to keep going as I contacted publishers in hopes of obtaining more physical copies of books. Many publishers returned from turbulent times and physical copies of books were difficult to obtain. However, as a committee member, it’s just easier to dig deeper with a text when you have a physical copy in front of you. Thankfully, publishers started returning to sending physical copies of books at the end of January and in February. We continue to be so thankful for the support many publishers extended to us as they worked diligently to send our committee books. However, that meant, that we had to read on a rigorous schedule and we often had to meet more than twice a month in order to have critical conversations around the literature. Here’s a figure that highlights our process as a committee: Recurrent Themes from the 2021 NCBLA List

Some of the 2021 NCBLA Books We invite you to see the power of literature across our 2021 NCBLA Book List!Jeanne Gilliam Fain is s a professor at Lipscomb University in Nashville, Tennessee and Chair of the 2021 Notables Committee.

2021 Notable Children's Books in the Language Arts Selection Committee Members

BY WENDY STEPHENS In addition to the ALSC awards described in the previous post, the Young Adult Library Association (YALSA) also designates award-winning and honor books for adolescent literature. Among the best-known awards for adolescent literature is the Michael L. Printz Award for Excellence in Young Adult Literature, administered by YALSA. However, there are many other opportunities to learn about exceptional literature for teens. The life and legacy of Margaret A. Edwards are honored through two award designations:

A shortlist of finalists for two of YALSA's flagship awards -- the YALSA Excellence in Nonfiction for Young Adults Award, honoring the best nonfiction books for teens and the William C. Morris Award, which honors a debut book written for young adults by a previously unpublished author, are announced in December, with the winner of each being part of the press conference.

In addition to designating award books, YALSA also compiles book list resources that can aid librarians and teachers in selecting books that appeal to young adults. A decade ago, YALSA moved four of its lists onto The Hub, its literature blog platform, so that youth services librarians involved in collection development could benefit from more real-time input. All four categories post throughout the year, leading to year-end lists reflecting that year's best titles. Those include:

Outside the Monday morning announcements, there are myriad other titles to explore. Among those, the United States Board on Books for Young People (USBBY) uses Midwinter to announce its Outstanding International Books (OIB) list showcasing international children's titles -- books published or distributed in the United States that originated or were first published in a country other than the U.S. -- that are deemed the most outstanding of those published during that year. RISE: A Feminist Book Project for ages 0-18, previously the Amelia Bloomer Project, is a committee of the Feminist Task Force of the Social Responsibilities Round Table (SRRT), that produces an annual annotated book list of well-written and well-illustrated books with significant feminist content for young readers. There are even genre fiction honors. For the past four years, the Core Excellence in Children’s and Young Adult Science Fiction Notable Lists designates notable children’s and young adult science fiction, organized into three age-appropriate categories, also announced at Midwinter. Next year, we will have another treat to look forward to when the Graphic Novel and Comics Round Table (GNCRT) inaugurates its Reading List. That's a lot of books! What are the can't-miss titles? I train my students to look for overlaps, like Candace Fleming winning this year for information text across age ranges. What does it indicate when the Sibert and YALSA's Nonfiction Award overlap? When a book is honored by both the Printz and YALSA Nonfiction? Though the in-person announcement is exhilarating, especially the view from the seats at the front of the auditorium reserved for committee members, the webcast approximates its energy and allows you to share with students in real-time. To make sure you catch all of the lists, follow the press releases from ALA News and on twitter. Until next January! Wendy Stephens is an Assistant Professor and the Library Media Program Chair at Jacksonville State University. BY WENDY STEPHENSEditorial Note: This post is the first in a 2-part series by Wendy Stephens discussing the rich landscape of book awards announced over the winter months. In this first post, Wendy focuses on ALSC awards and awards by ALA affiliates recognizing books for children or books for a wide spectrum of age groups. The second post, which will be published next week, will present awards for YA literature administered by YALSA, as well as several other notable awards. When we talk about budgeting for materials, I always advise my school librarian candidates to be sure to save some funding for January. No matter how good their ongoing collection development has been throughout the year, there are always some surprises when the American Library Association's Youth Media Awards (YMAs) roll around, and they'll want to be able to share the latest and best in children's literature with their readers. These are the books that will keep their collections up-to-date and relevant. From our own childhoods, we always remember the "books with the medals" -- particularly the John Newbery for the most outstanding contribution to children's literature and the Randolph Caldecott for the most distinguished American picture book for children. These books become must-buys and remain touchstones for young readers. In 2021, Newbery is celebrating its one hundredth year. Some past winners and honor books are very much a product of their time, and many of those once held in high esteem lack appeal today. For those of us working with children and with children's literature, the new books honored at Midwinter offer opportunities to revisit curriculum, update mentor texts, and build Lesesneian "reading ladders." Each award committee has its own particular award criteria and guidelines for eligibility, and its own process and confidentiality norms. Every year, the YMAs seems to be peppered with small surprises. Does New Kid winning the Newbery means graphic novels are finally canonical? Is Neil Gaiman an American? What about all the 2015 Caldecott honors, including the controversial That One Summer? Did the Newbery designation of The Last Stop on Market Street mean you can validate using picture books with older students? How does Cozbi A. Cabrera's much-honored art work resonate at this historical moment? In Horn Book and School Library Journal, Newbery, Caldecott and Printz contenders are tracked throughout the year in blogs like Someday My Printz Will Come, Heavy Medal, and Calling Caldecott. Other independent sites like Guessing Geisel, founded by Amy Seto Forrester are equally devoted to award prediction. Among librarians and readers, there are lots of armchair quarterbacks, and conducting mock Newbery and Caldecotts, either among groups of professionals or with children, have become almost a cottage industry. There are numerous how-tos on that subject, from reputable sources like The Nerdy Book Club and BookPage. But there are numerous other awards announced at ALA Midwinter almost simultaneously that deserve your attention, too. Among the Association for Library Services for Children (ALSC) awards are: the Robert F. Sibert Medal, the Mildred L. Batchelder Award, the Geisel Award, the Excellence in Early Learning Digital Media Award, and the Children's Literature Legacy Award.

Aside from the award winners, each year annual ALSC Children's Notable Lists are produced in categories for Notable Children's Recordings, Notable Children's Digital Media, and Notable Children's Books. If you want to see the machinations behind the designation, those discussions are open to the public this year via virtual meeting links. Outside of ALSC, many of ALA’s affiliates have their own honors for children's literature. These include the Ethnic and Multicultural Information Exchange Round Table (EMIERT) which sponsors the Coretta Scott King Book Awards; the Association of Jewish Libraries which sponsors the Sydney Taylor Book Awards; and REFORMA: The National Association to Promote Library and Information Services to Latinos and the Spanish-Speaking which sponsors the Pura Belpré awards. In addition to these affiliates, others such as the Asian/Pacific American Librarian Association and the American Indian Library Association also present awards. The awards are always evolving to reflect the abundance of literature available for young people. Like the Association of Jewish Libraries and the Asian/Pacific American Librarian Association awards, the American Indian Youth Literature Awards were first added to the televised YMA event in 2018. And this year was the first year for inclusion for a new Young Adult category for the Pura Belpré. Two awards of particular significance are the Stonewall Book Award – Mike Morgan and Larry Romans Children’s and Young Adult Literature Awards are given annually to English-language works found to be of exceptional merit for children or teens relating to the gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender experience, and the Schneider Family Book Awards, honoring authors or illustrators for the artistic expression of the disability experience for child and adolescent audiences, with recipients in three categories: younger children, middle grades, and teens.

Wendy Stephens is an Assistant Professor and the Library Media Program Chair at Jacksonville State University. BY ALLY HAUPTMAN

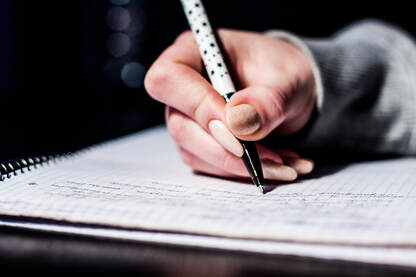

The Steps

1. Choose a text. It might be a brilliantly written and illustrated picture book, an excerpt from a middle grades or YA novel, or even an interesting infographic. 2. Share the text with your students and model what writing ideas you have based on this text. 3. After reading, ask the questions, “What writing ideas do you get from this text? What are the possibilities you see as a writer?” 4. Get out of the way and let kids write and create! 5. Give students time to share and learn from each other. That’s it...five steps that lead to important discussion and writing possibilities. The following is an example of this writing lesson in action with two of my own children. I started by reading Malala’s Magic Pencil by Malala Yousafzai. The book begins with Malala talking about a television program she used to watch. The show’s main character was a boy with a magic pencil who Malala saw as a hero, always helping others. She dreamed of having her own magic pencil. She goes on to tell her story of fighting for girls’ education, realizing that she really did have a magic pencil all along. She was able to change the world with her pencil as she fought for educational equality. The last line in the book reads, “One pen, one teacher, one student can change the world.” Here is the key to this lesson, and this is how I get out of the way of their creativity. I asked my children to write for ten minutes about what ideas they got from Malala’s Magic Pencil. It is as simple as that. I did not give them my prompt that might be presented from this book such as, “What would you do with a magic pencil?” I let them figure out how this book would be a mentor text for their own writing. The beauty of presenting a text and then letting students figure out their own writing possibilities is that they bring their background knowledge, voice, and writing style and combine it with the author’s ideas from the text presented. When you present a mentor text and ask the students to see the writing possibilities, the variety is astounding. Just with my own daughters, my fifth grader, who is the youngest and always trying to prove herself to her sisters, wrote about a magic tree. In her story, no one believes her that this tree is magic and she hatches a plan to show everyone that she is right. She brought in her ideas and showed strong voice. My eighth grade daughter decided to write about the Infiniti Pen. It is worth mentioning that all of my daughters are obsessed with Marvel movies. So, the Infiniti Pen was inspired by Thor’s hammer in that only the worthiest person in the village could pick up the pen because of its persuasive powers. In this piece, my daughter chose to bring in her own voice and combine Marvel with Malala’s ideas. These writers were able to choose their ideas and use their voices. When we present possibilities through mentor texts, readers also begin to read like writers. Try it. Read a book and ask your students to find writing possibilities, to write for ten minutes and see where it may lead! The following list includes texts I have used to spark writing ideas over the past few years with teacher candidates, K-12 students, and my own children. 25 books with endless possibilities…

After the Fall by Dan Santat Animals by the Numbers by Steve Jenkins Bookjoy, Wordjoy by Pat Mora, illustrated by Raúl Colón Camela Full of Wishes by Matt de la Pena, illustrated by Christian Robinson Claymates by Dev Petty, illustrated by Lauren Eldridge Coco: Miguel and the Grand Harmony by Matt de la Pena, illustrated by Ana Ramírez Cute as an Axolotl by Jess Keating, illustrated by David DeGrand Drawn Together by Minh Lê, illustrated by Dan Santat Dude! by Aaron Reynolds, illustrated by Dan Santat Dreamers/Sonadores by Yuyi Morales Friends and Foes: Poems About Us All by Douglas Florian Imagine by Juan Felipe Herrera, illustrated by Lauren Castillo Jabari Jumps by Gaia Cornwall Love by Matt de la Pena, illustrated by Loren Long Malala’s Magic Pencil by Malala Yousafzai, illustrated by Kerascoёt Maybe Something Beautiful: How Art Transformed a Neighborhood by F. Isabel Campoy and Theresa Howell, illustrated by Rafael López Nope! by Drew Sheneman The Day You Begin by Jacqueline Woodson, illustrated by Rafael López The Girl With a Mind for Math: The Story of Raye Montague by Julia Finley Mosca, illustrated by Daniel Rieley The Wolf, the Duck, and the Mouse by Mac Barnett, illustrated by Jon Klassen The Word Collector by Peter H. Reynolds They All Saw a Cat by Brendan Wenzel Water Land by Christy Hale What Makes a Monster? by Jess Keating, illustrated by David DeGrand Wild World by Angela McAllister, illustrated by Hvass & Hannibal Ally Hauptman is a CLA Board Member and is the Chair of the Ways and Means Committee. She is an associate professor at Lipscomb University in Nashville, TN. Image by Tookapic from Pixabay

|

Authors:

|

CLA

About CLA

|

Journal of Children's Literature

Write for JCL

|

ResourcesCLA-sponsored NCTE Position Statements

|

Members-Only Content

CLA Video Library

|

© COPYRIGHT 2018.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed