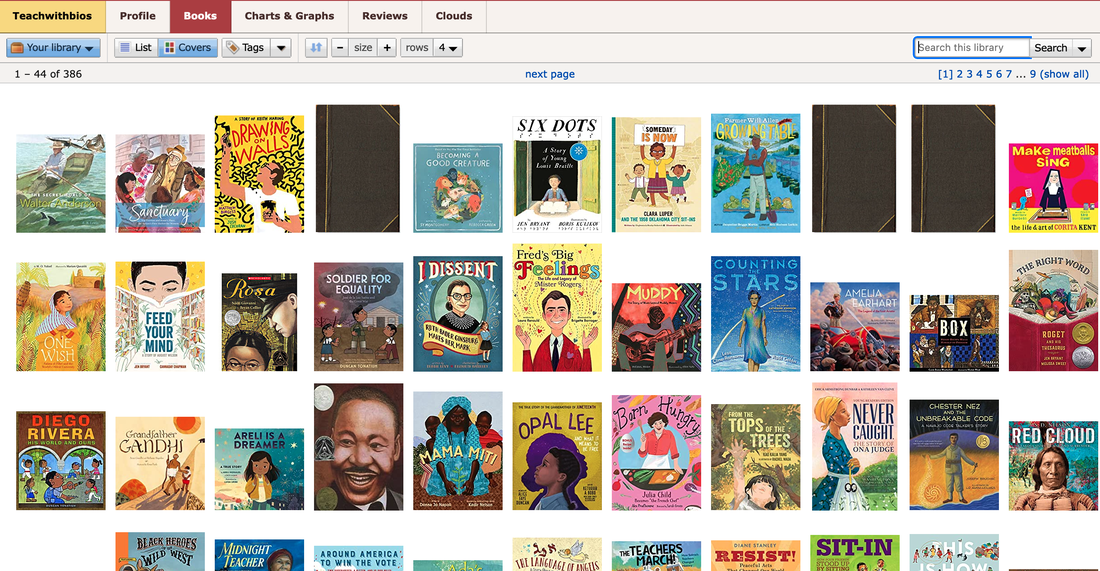

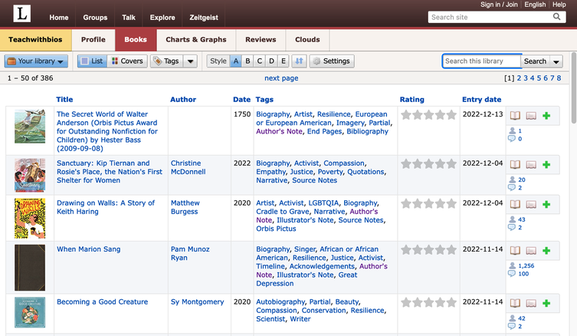

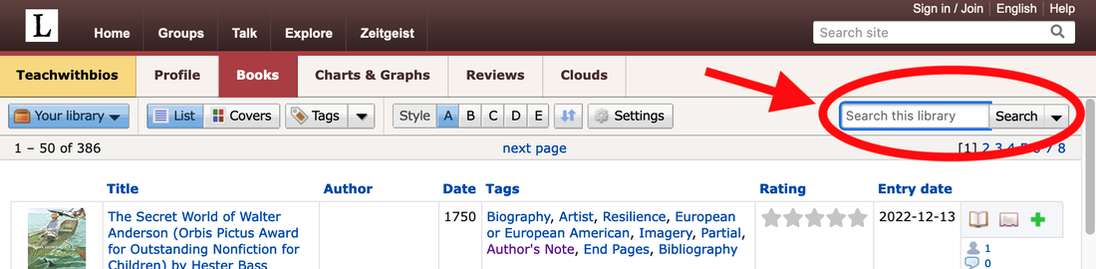

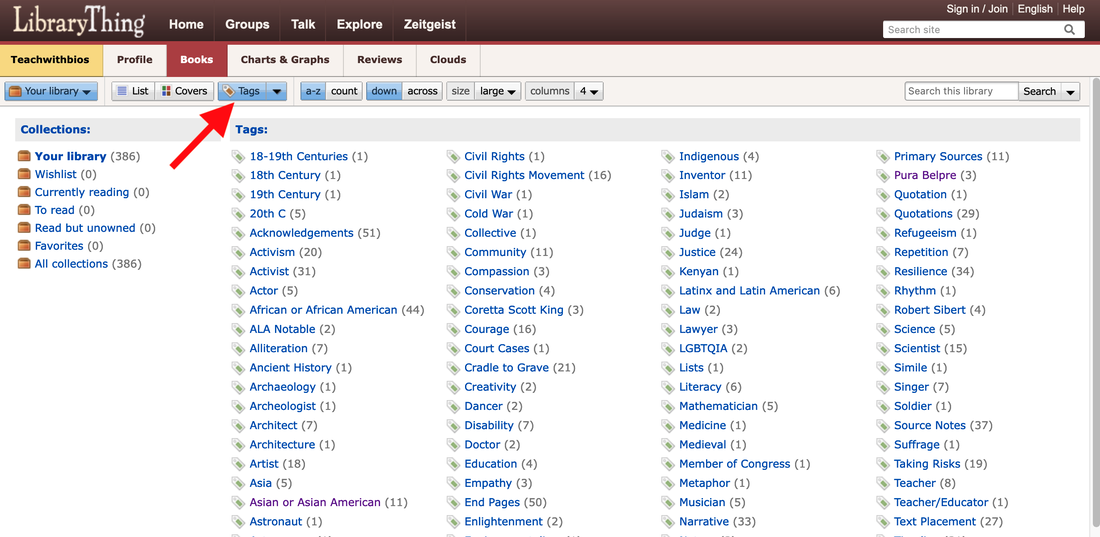

By Xenia Hadjioannou & Mary Ann Cappiello on behalf of the Biography Clearinghouse  Wondering how to find and curate biographies suited to the interests of your students or to your curricular needs? Frustrated by a piecemeal approach, cross-referencing booklists, award lists, and Google searches? The Biography Clearinghouse has a year end gift for you! We have created a collection of biographies for young people on LibraryThing, an online book cataloging service. The collection makes use of “tags” with which users can use to guide and focus their searches. This continually updated collection is intended as a tool for educators of all subjects and age groups, librarians, and anyone else who enjoys and works with biographies. We are busily tagging the books in our collection and will continue to add and tag more titles! The best part about it? You can access our collection for free and without having to sign up for an account. You can search the collection by theme, literary elements, geographic location, format feature, profession/discipline, etc. To learn how to access, navigate, and search through the Biography Clearinghouse Collection review the information below. How do I access the Biography Clearinghouse Collection?

Simply go to https://www.librarything.com/catalog/Teachwithbios. There you will see our entire catalog listing. In the “Tags” column you will see all the tags assigned to each book by members of the Biography Clearinghouse.

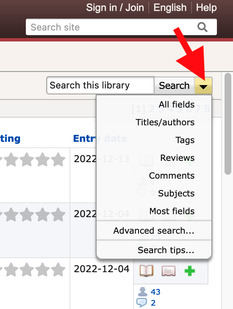

How do I search through your catalog?

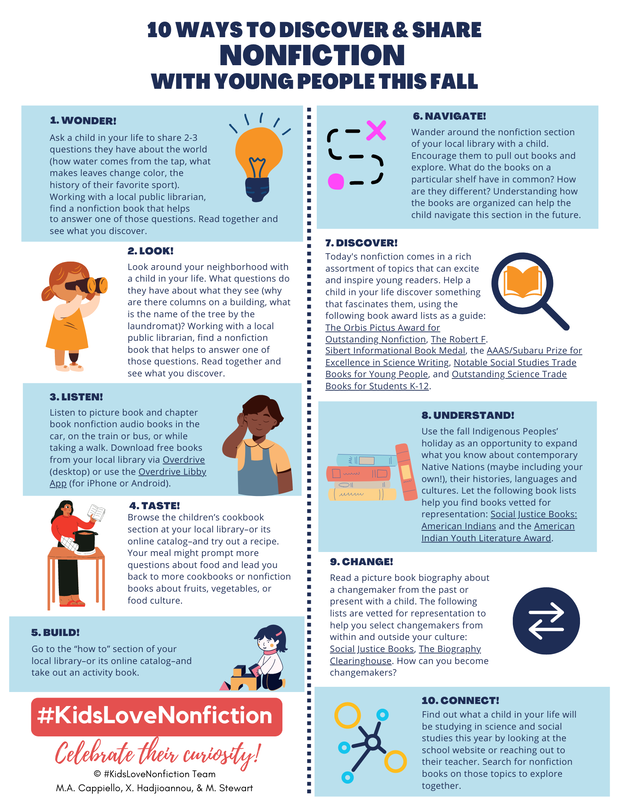

Clicking on a tag will produce a listing of all books in our catalog we have annotated with it. Have any questions? Biographies to add to our collection? Suggested tags? Please email us at [email protected]. We’d love to hear from you. Xenia Hadjioannou is an Associate Professor of Language and Literacy Education at the Berks campus of Penn State University where she teaches and works with preservice teachers through various courses in language and literacy methodology. Xenia is the co-author of Translanguaging for Emergent Bilinguals. She is the Vice President and Website Manager of the Children's Literature Assembly, and a co-editor of The CLA Blog. Mary Ann Cappiello is a Professor of Language and Literacy at Lesley University, where she teaches courses in children’s literature and literacy methods. For twelve years, she blogged about teaching with children’s literature at The Classroom Bookshelf. She is a former chair of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8. Mary Ann is the coauthor of Text Sets in Action: Pathways Through Content Area Literacy (2021). By Mary Ann Cappiello, Xenia Hadjioannou, and Melissa Stewart We are fortunate to be in the midst of a golden age for nonfiction literature for young people. Today’s nonfiction pushes boundaries in form and function, and its creators write about an ever expanding array of topics. In these books, young people encounter well-researched and nuanced explorations of cutting edge scientific discoveries, underexplored moments throughout history and in our current time, compelling accounts of historically marginalized and minoritized communities and perspectives, and more. As we advocated in our February 14, 2022, letter to The New York Times, #KidsLoveNonfiction! Indeed, several researchers investigating the reading habits and preferences of young children report that, when given the opportunity to self-select, the majority of children enjoy nonfiction as much as or more than fiction (Correia, 2011; Ives et al. 2020; Mohr, 2006; Repaskey et al., 2017). Yet, adults often assume that young people would rather read fiction, and are therefore hesitant to make nonfiction titles available to children or to devote time to exploring nonfiction with the young people in their lives. As the school year begins, we want to remind all adults who are involved in the reading lives of children that:

To raise awareness of the potential of nonfiction books to empower young people by feeding their interests and creating pathways to their passions, we’ve created the flyer 10 Ways to Discover & Share Nonfiction with Young People this Fall. We hope it will find its way onto classroom walls, library displays, and home fridges and inspire teachers, librarians, parents, and all people who read with children. Have a wonderful school year!

References Correia, M. P. (2011). Fiction vs. Informational Texts: Which Will Kindergartners Choose? Young Children, 66(6), 100–104. Ives, S. T., Parsons, S. A., Parsons, A. W., Robertson, D. A., Daoud, N., Young, C., & Polk, L. (2020). Elementary Students’ Motivation to Read and Genre Preferences. Reading Psychology, 41(7), 660–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2020.1783143 Mohr, K. A. J. (2006). Children’s Choices for Recreational Reading: A Three-Part Investigation of Selection Preferences, Rationales, and Processes. Journal of Literacy Research, 38(1), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3801_4 Repaskey, L. L., Schumm, J., & Johnson, J. (2017). First and Fourth Grade Boys’ and Girls’ Preferences For and Perceptions About Narrative and Expository Text. Reading Psychology, 38(8), 808–847. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2017.1344165 Mary Ann Cappiello teaches courses in children’s literature and literacy methods at Lesley University, blogs about teaching with children’s literature at The Classroom Bookshelf and Text Sets and Trade Books, and is a founding member of The Biography Clearinghouse. She is a former chair of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8. Xenia Hadjioannou is associate professor of language and literacy education at the Berks campus of Penn State University. She is vice-president of CLA and co-editor of the CLA Blog. She is a founding member of The Biography Clearinghouse. Melissa Stewart is the award-winning author of more than 200 science-themed nonfiction books for children and co-author of 5 Kinds of Nonfiction: Enriching Reading and Writing Instruction with Children’s Books. Her highly-regarded website features a rich array of nonfiction writing resources. By: William Bintz & Meghan ValerioPicture books are for everybody at any age, not books to be left behind as we grow older. (Anthony Browne, 2019)

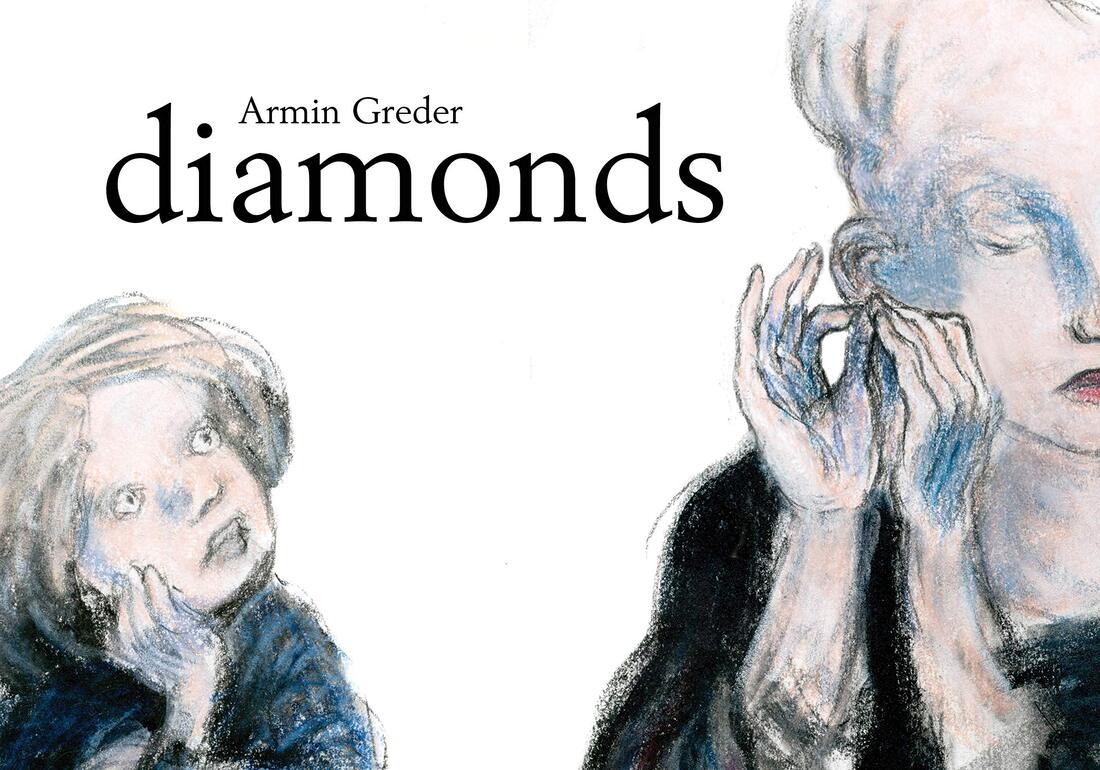

This intriguing diamond industry story depicts the controversial journey of diamonds from source to customer, including the appalling conditions, black market, and blind ignorance of customers rich enough to purchase them. It is a disturbing and evocative depiction of how the diamond industry, historically and contemporaneously, feeds an insatiable appetite for diamonds, and in the process, also perpetuates inequality, conflict, and corruption. Metaphorically, this visually unsettling book removes the sparkle from diamonds. Diamonds (Greder, 2020) is not a novel, short story, nor poem. It is a picturebook, with approximately 32 pages, minimal text (195 words), and single and double-spread illustrations. It is not, however, a traditional picturebook – it is a crossover picturebook (see Table 1 for more examples).

Benefits of Crossover PicturebooksCrossover picturebooks invite teachers to shift perspectives and think differently about the nature of childhood and the purpose of curriculum. In terms of childhood, crossover picturebooks posit that teachers Never Read Down, Always Read Up to children. Reading down sees the child as innocent and in need of protection; reading up sees the child as capable of understanding sophisticated topics (Dressang & Kotrla, 2009). Reading down suggests that limiting or eliminating access to controversial issues protects the innocence of children; reading up conceives the danger of withholding information from youth as exceeding the danger of providing it (Dressang, 1999). Curriculum utilizing crossover picturebooks is rooted in an inquiry-based model. This model builds on curiosity and supports inquiry for teachers and students. Within this model, instruction based on crossover picturebooks:

A Concluding, But Not Final, ThoughtPicturebooks are synonymous with children’s literature. But is this a necessary condition of the art form itself? Or is it just a cultural convention, more to do with existing expectations, marketing prejudices and literary discourse? There is no reason why a 32-page illustrated story can’t have equal appeal for teenagers or adults as they do for children (Tan, 2003, np). We end with a concluding, not a final, thought, because we hope this post will start new conversations, not close them down. This thought is eloquently expressed by internationally renowned author and illustrator, Shaun Tan. Yes, picturebooks have been, and continue to be, synonymous with children’s literature. Is it time to shift perspective and think differently about this kind of literature? If so, we believe crossover picturebooks are a good conversation starter for readers of all ages. References

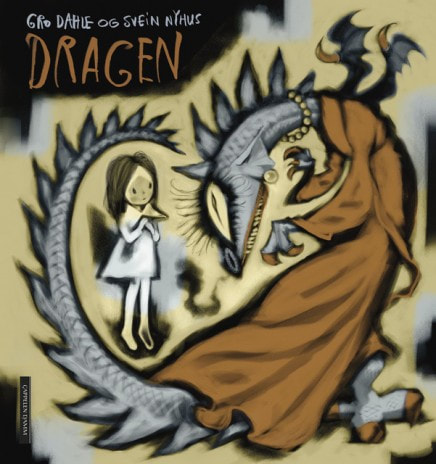

Meghan Valerio is a doctoral student in Curriculum and Instruction with a Literacy emphasis at Kent State University. Meghan’s research interests include investigating literacy and cognitive development from a critical literacy perspective, centering curricula to understand reading as a transactional process, and exploring pre- and in-service teacher perspectives in order to enhance literacy instructional practices and experiences. William Bintz is Professor of Literacy Education in the School of Teaching, Learning, and Curriculum Studies at Kent State University. His professional interests include the picturebook as object of study, literature across the curriculum K-12, and collaborative qualitative literacy research. BY MEGHAN VALERIO & WILLIAM BINTZRecently, I (William) introduced crossover picturebooks in a graduate literacy course to students pursuing a reading specialization Master’s degree. All students were practicing teachers ranging from elementary through high school. Each week, I read aloud a crossover picturebook to introduce the class session. Selected picturebooks dealt with themes including death and dying, divorce, suicide, mental illness, physical disability, parent-child separation, and other life-changing and impactful events. One example is Dragon by Gro Dahle (2018). It tells the story of Lilli, a young girl who is a child abuse victim by her mother. Lilli regards her mother as a dragon because she is explosive, hot-tempered, and abusive. After reading, I invited students to share their questions and reactions to crossover picturebooks. Three questions and one reaction were particularly illustrative:

These responses inspired this blog post. They revealed teachers may not know much about crossover literature but are curious to know more about it. What are Crossover Picturebooks?Crossover literature, or texts written for dual-aged audiences, is not a new genre, as many books could be considered crossover already. While picturebooks specifically might be enjoyed by both children and adults, crossover picturebooks, a subset of crossover literature, are written and illustrated intentionally for both children and adults, breaking conventional assumptions that books are intended for one age group (Falconer, 2008; Harju, 2009, Rosen, 1997). Crossover authors communicate purposeful messages to both audiences equally (Harju, 2009). Narratives then are considered ageless and timeless, often portraying issues that might be deemed controversial including death, verbal and physical abuse, and divorce. In a world where in-person and online book shopping and borrowing is organized by genre and age, this makes these “ageless” books complex. Consider first an adult purchasing a picturebook for themselves, and on the flip side, encouraging a child to purchase a book about abuse. Both instances could be questionable, even alarming to some. While there are truly designated texts for children, like aesthetic and sensory appealing babybooks (Kümmerling-Meibauer, 2015), crossover picturebooks defy traditional book categorizing norms, causing anyone interested to rethink what counts as children’s literature vs. adult. Children’s literature though is written and published by adults for children (Rosen, 1997). So really, is there such a thing as a true children’s book if the text isn’t written by children at all? What Concerns Does This Raise?Currently, we are conducting research on crossover picturebooks. Specifically, we are exploring teacher concerns on using this literature in the classroom. Based on this research, two major findings indicate that many K-12 teachers worry about the following issues:

These concerns, and many others like them, are real for teachers. Traditionally, children’s literature is to be enjoyable not uncomfortable, entertaining not controversial. Crossover literature invites a different perspective and pushes the envelope on censorship and what constitutes taboo topics in classrooms. To help explore this further, we recommend the following resources. These resources include picturebooks and professional literature that have pushed our thinking about crossover literature. We hope they will push yours.

ReferencesBishop, R.S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6 (3). Falconer, R. (2008). The Crossover Novel: Contemporary Children’s Fiction and Its Adult Readership. London, UK: Routledge. Harju, M.L. (2009). Tove Jansson and the crossover continuum. The Lion and the Unicorn, 33(3), 362-375. Kümmerling-Meibauer, B. (2015). From baby books to picturebooks for adults: European picturebooks to the new millennium. Word & Image, 31 (3), 249-264. Rosen, J. (1997). Breaking the age barrier. Publishers Weekly. 243 (6). Meghan Valerio is a doctoral student in Curriculum and Instruction with a Literacy emphasis at Kent State University. Meghan’s research interests include investigating literacy and cognitive development from a critical literacy perspective, centering curricula to understand reading as a transactional process, and exploring pre- and in-service teacher perspectives in order to enhance literacy instructional practices and experiences. William Bintz is Professor of Literacy Education in the School of Teaching, Learning, and Curriculum Studies at Kent State University. His professional interests include the picturebook as object of study, literature across the curriculum K-12, and collaborative qualitative literacy research. BY LAUREN AIMONETTE LIANG Last year, right around this time, the Fall 2019 issue of JCL arrived in the mail. In the President’s Message I had written a bit about my excitement for the upcoming NCTE conference: It starts for me with the airplane travel. Coming from my area, it is rare to board a flight heading to a major conference and not encounter fellow teachers, librarians, and researchers embarking on the same adventure. We wave, ask about colleagues and friends, and buzz a bit with excitement. (I often think the other travelers must later wonder about these groups of individuals who are all grading papers and reading thick books, while simultaneously winning all the in-flight trivia and scrabble games.) Once we arrive at the NCTE city, conference-goers from all over are grabbing bags, looking for shuttles and taxis, and heading off to the area hotels. Immediately there is a shared sense of purpose and anticipation. Conversations break out in the hotel elevators about whether registration is open, and the time of the opening session. Hordes of badge-wearing, tote-bag laden attendees appear in long lines at the coffee stands and take over the sidewalks in their sensible walking shoes as they head off for the day. And then the conference! Hour after hour of thought-provoking sessions, with speakers addressing the important issues in our field, provoking new ideas, and sharing possible solutions. The vibrant displays of new books in the exhibit hall waiting to be shared by knowledgeable and enthusiastic publishers who offer sneak peeks that might be perfect for your classroom. And, best of all, that amazing shared sense of being present with each other—knowing that the people gathered here care just as deeply as you do about supporting children’s and teen’s literacy experiences and growth. The Children’s Literature Assembly events at NCTE are a highlight for many attendees. A history of consistent excellence makes our CLA Notables Session, CLA Master Class, and CLA Breakfast the starred events on many personal conference schedules...

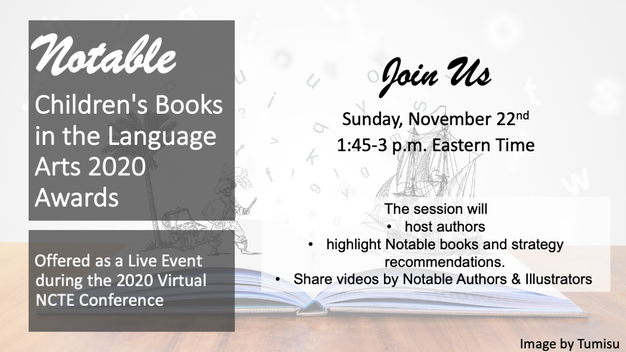

Notable Children’s Books in the Language Arts AwardS

Join the members of the Notable Children’s Books in the Language Arts award committee in a live event on Sunday afternoon from 1:45- 3:00 pm ET. Throughout the fall this blog has featured posts from members of this committee. Join them live for more outstanding 2020 titles and suggestions for classroom use.

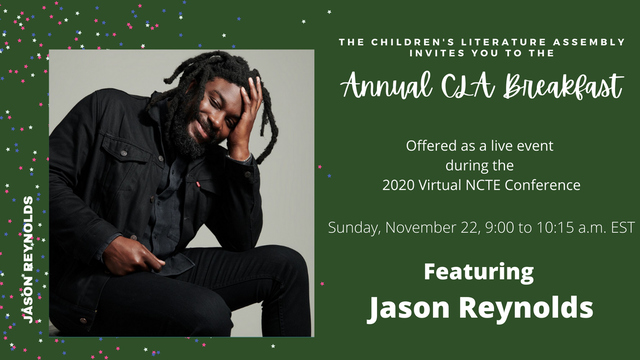

Annual CLA Breakfast

Bring your breakfast to listen to amazing author Jason Reynolds, this year’s CLA Breakfast keynote speaker! In a live session Sunday morning from 9:00 – 10:15 am ET, the 2020-21 National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature will talk about his writing and more.

Lauren Aimonette Liang is an associate professor at the University of Utah and the current president of CLA. Living Literately and Mindfully at the Intersection of Mother Nature, the Animal World and Poetry11/9/2020

BY PEGGY S. RICE Consider...

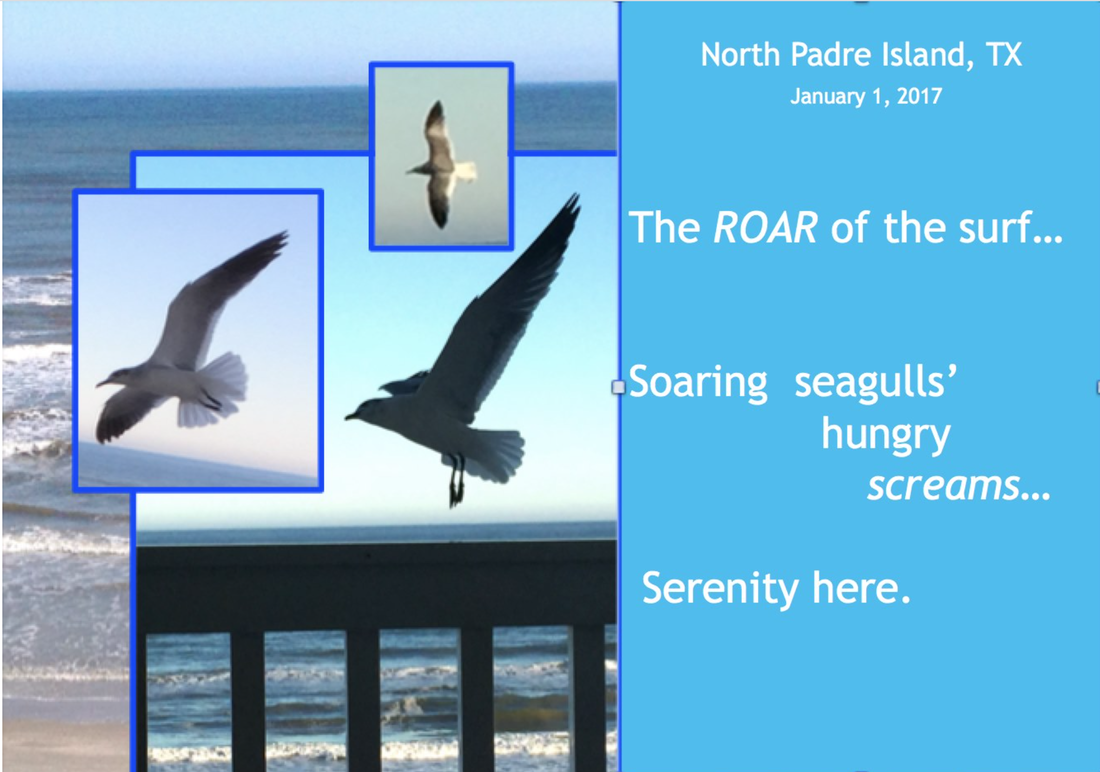

Serenity can be found at the intersection of Mother Nature, the animal world and poetry. I have found that the more time I spend at this intersection, the less anxiety I feel. Following are materials and strategies, my students, daughter and I have found successful:

Poetry Performance

Power of Place Locate a space surrounded in nature that you can visit regularly. I am fortunate, because I live on 7 acres with a pond. When visiting this space, be prepared to engage in mindful listening, see the world with a poet’s eyes and take notes in a writing journal.

Poetry Writing Writing poetry is all about playing with words. Fletcher (2002) encourages us to play with the sounds of words. Consider, rhythm, rhyme, repetition, onomatopoeia and alliteration. He also encourages us to think fragments/cut unnecessary words, consider shape, use white space/experiment with line breaks and end with a bang/sharpen the ending. Each of these aspects of language can be a topic of minilessons connected to poetry performances of mentor poems. Lewis (2012, 2015) has included excellent resources for writing formula poems. Savor... In Beauty May I Walk --Anonymous (Navajo Indian) In beauty may I walk All day long may I walk Through the returning seasons may I walk Beautifully will I possess again Beautifully birds Beautifully joyful birds On the trail marked with pollen may I walk With grasshoppers about my feet may I walk With dew about my feet may I walk With beauty may I walk With beauty before me may I walk With beauty behind me may I walk With beauty above me may I walk With beauty all around me may I walk In old age, wandering on a trail of beauty, lively, may I walk. In old age, wondering on a trail of beauty, living again, may I walk It is finished in beauty It is finished in beauty References

Calkins, L.M. (1994). The art of teaching writing. (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Fletcher, R. (2002). Poetry matters: Writing a poem from the inside out. New York: Harper Trophy. Lewis, J. P. (2015). National geographic book of nature poetry: More than 200 poems with photographs that float, zoom, and bloom! Washington, DC: National Geographic Partners, LLC. Lewis, J. P. (2012). National geographic book of animal poetry: More than 200 poems with photographs that squeak, soar, and roar! Washington, DC: National Geographic Partners, LLC. Shelton, L. (2009). Banish boring words. New York: Scholastic Peggy S. Rice is an Associate Professor of Elementary Education and Faculty Advisor for the Partners in Literacy Council at Ball State University in Muncie Indiana. She is a member of the Children's Literature Assembly Ways and Means Committee. |

Authors:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CLA

About CLA

|

Journal of Children's Literature

Write for JCL

|

ResourcesCLA-sponsored NCTE Position Statements

|

Members-Only Content

CLA Video Library

|

© COPYRIGHT 2018.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed