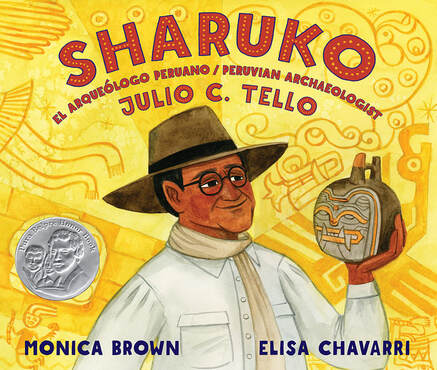

By Amina Chaudhri and Julie Waugh, on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse One of the most profoundly devastating schemes of the colonial project was to erase Indigenous knowledge: religious, intellectual, social, cultural, aesthetic, scientific. In the Afterword of Sharuko, Monica Brown extends readers’ knowledge of the importance of Julio C. Tello’s work as an archaeologist in undoing the damage of colonial erasure. He spent his life raising awareness about Indigenous Peruvian ways of knowing, as evidenced by his research. Julio C. Tello was Indigenous and spoke Quechua, so his investment in countering the dominant narrative was personal as well as professional. Today, he is a celebrated figure in Peru, and through Sharuko, young readers can come to value his accomplishments as well. This entry of The Biography Clearinghouse offers a variety of teaching and learning experiences to use with Sharuko: el Arqueólogo Peruano/Peruvian Archaeologist, a bilingual biography of Julio C. Tello, written by Monica Brown, and illustrated by Elisa Chavarri. In addition to a recorded interview with the author in which she discusses her research process and the craft of creating picturebook biographies, we include suggestions for learning about Peruvian textiles, the Quechua language, and variations on the trait of bravery. Below are two ideas inspired by Sharuko. Connecting the Past and the Present Sharuko is the biography of a man who lived from 1880 - 1947, yet his work as an archeologist and conservationist is relevant today. His legacy includes the Museum of Anthropology, in Lima Peru, that houses the artifacts he discovered and wrote about. His research spotlights the accomplishments of Indigenous Peruvians and tells the story of Peru’s past that colonialism tried to erase. In her interview, Monica Brown tells us about a “magic moment” in the process of creating this book, in which she imagined a Quechua word - sharuko- emblazoned across the front as its title. In this way she continues Tello’s legacy, using her privilege as an established writer to highlight the Quechua language and the contributions Tello, an Indigenous scholar, made to the world. Begin by reading Sharuko aloud with students, inviting them to note the chronology of his life, from boy to researcher, the people who supported him along the way, and his connections to history as depicted in the text and images. In analyzing this biography, teachers might scaffold students’ understandings of:

Thinking Like an Archeologist Sharing Sharuko can provide a similar introduction to the complexities and exciting puzzles that define the field of archeology. Archeology is about telling the human story. Invite your students to act as archeologists, researching, writing, and considering the different perspectives that inform archeological work. Teachers can find teaching ideas related to archeology on the website of The Society of American Archeology. The teaching and learning suggestions below are designed for teachers to plan experiences that involve thinking like an archeologist:

For more teaching and learning suggestions, visit the complete entry on Sharuko, on The Biography Clearinghouse website. Amina Chaudhri is an associate professor at Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago, where she teaches courses in children's literature, literacy, and social studies. She is a reviewer for Booklist and a former committee member of NCTE's Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction for Children. Julie Waugh shares a 4th grade teaching position at Zaharis Elementary in Mesa, AZ and serves as an Inquiry Coach for Mesa Public Schools. She delights in the company of children surrounded and inspired by books. A longtime member of NCTE, and an enthusiastic newer member of CLA, Julie is a former committee member of NCTE's Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction for Children. BY XENIA HADJIOANNOU, LAUREN LIANG & LIZ THACKERAY NELSON Thank you to the Outgoing CLA Board Members

Term: January 1, 2020 - December 31, 2021Congratulations to the Newly Elected CLA Board Members

Term: January 1, 2022 - December 31, 2024

By Joanne YiAt the tail end of 2020, I completed my dissertation, a large-scale study of Asian American children’s literature. In total, I immersed myself in over 350 Asian American picturebooks, published across the last 25 years. This number surprises many, in part, because it is admittedly a large number to study, but also because few Asian American, bicultural stories are popularly known beyond perennial classroom favorites such as The Name Jar (Choi, 2001) and My Name is Yoon (Recorvits, 2003). Below, I share an adapted excerpt of this work and suggest titles for teachers, librarians, and parents to read and learn about beautiful and resilient Asian American identities and experiences: The last few years have brought to light the increasing importance of the #OwnVoices movement in publishing, which highlights and buoys stories that authentically reflect their authors. In my analysis of Asian American picturebooks, it was evident the stories written by Asian American authors were often tomes of lived experience. They included family histories in prison camps, refugee journeys, memories of grandparents, difficult immigration experiences, and much more. As I read Love As Strong As Ginger (Look, 1999), Hannah is My Name (Yang, 2004), A Different Pond (Phi, 2017), and Drawn Together (Le, 2017), I felt pangs of recognition as I recalled my childhood. These picturebooks were Asian American counterstories (Delgado, 1989), narratives that were different in content, perspective, and ideology from those reflecting the mainstream. The latter often racializes Asian American characters, stereotyping them as a monolith, as perpetual foreigners, and as model minorities. In contrast, the power of counterstories is, as Couzelis (2014) wrote, their “potential to destabilize dominant national myths that act as ‘universal’ histories” (p. 16). It is important to realize that many of these stories were intentionally created to provide Asian American representation. Many stories were inspired by the authors’ own childhoods in the United States and were often tied to specific memories, such as playing with cousins while the adults played mahjong or fishing for that evening’s supper, rather than general experiences, such as moving or acclimating to a new school. Several of the texts that disrupted stereotypical tropes did so because the illustrators figuratively drew themselves into stories not originally written with Asian American characters in mind. It’s no small matter that illustrator Louie Chin depicted Asian American siblings in a silly story about dinosaurs crashing a birthday party (Don’t Ask a Dinosaur, 2018), for example, or that Yumi Heo perceived Bombaloo, an imagined manifestation of anger and petulance, as a little Korean American girl (Sometimes I’m Bombaloo, 2002). These stories are meaningful, not because the starring role in a “White” story was filled by an Asian American, but because the stories finally aligned with the imaginations and realities of Asian American children themselves. The difference lies in stories from Asian Americans and storying about Asian Americans. Myths of the model minority are laid bare with authors’ own stories and family histories of poverty, post-immigration traumas, language barriers, and cultural clashes. They are in stark contrast to those more commonly heard tales of joyous overseas adoptions, racially ambiguous people, fearsome ninjas, and fragile origami, and the myths that come with them. Such stories do not produce connections or reflections for readers. Rather, the defining characteristic of the most notable picturebooks was their commitment to authenticity and the telling of lived experiences. Recommendations for Picture Books I encourage educators and families to explore the diverse richness of Asian America and share these stories with the children in their care.

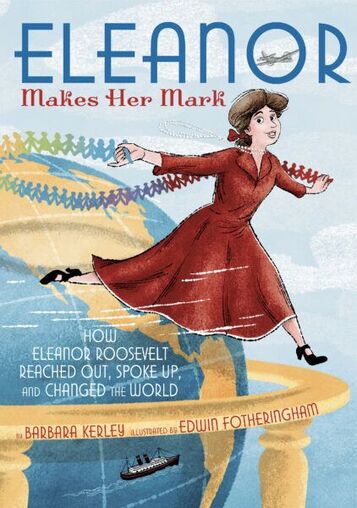

Dissertation excerpt adapted from Yi, J. H. (2020). Representations, Racialization, and Resistance: Exploring Asian American Picturebooks, 1993–2018 (Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University). References Couzelis, M .J. (2014). Counter-storytelling and ethnicity in twenty-first-century American adolescent historical fiction (UMI No. 3620806) [Doctoral Dissertation, Texas A&M University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. Delgado, R. (1989). Storytelling for oppositionists and others: A plea for narrative. Michigan Law Review, 87(8), 2411–2441. Joanne Yi earned her PhD in Literacy, Culture, and Language Education from Indiana University. A proud MotherScholar and former elementary teacher from Philadelphia, her research interests include critical literacies, textual analysis of diverse children’s literature, issues of inclusion and belonging in elementary and early childhood contexts, and reading education. By Mary Ann Cappiello and Jenn Sanders, on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse  “The purpose of life, after all, is to live it, to taste experience to the utmost, to reach out eagerly and without fear.” This quote greets readers of Barbara Kerley and Edwin Fotheringham’s latest collaboration, Eleanor Makes Her Mark: How Eleanor Roosevelt Reached Out, Spoke Up, and Changed the World. Kerley drops her readers right into the busy preparations for Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first inauguration, grounding readers in Eleanor’s public identity as the forthcoming First Lady. But then Kerley brings the readers back in time to Eleanor’s unhappy childhood and early adolescent years. Kerley’s characterization of Eleanor builds across the text: shy and quiet girl, engaged intellectual, socialite seeking purpose by teaching calisthenics in settlement houses and researching working conditions in garment factories, and, ultimately First Lady of the United States. As First Lady, Eleanor’s travels continued around the United States and across the Globe as she investigated working conditions, discrimination, and the effects of the devastation of The Great Depression and World War II. Kerley concludes the biography with Eleanor’s position as delegate to the newly formed United States General Assembly, working on the committee that authored the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Throughout the book, illustrator Edwin Fotheringam works with visual metaphors to emphasize Eleanor’s unflagging energy and her ability to bring people together. In the cover illustration, Eleanor jumps off of a globe, streaming a banner of paper dolls holding hands that trails in her wake. Fotheringham peppers the book with swirling lines of motion, highlighting Eleanor’s boundless verve, vivacity, and constant travel. Fotheringham also continues the hand-holding motif throughout the book to reinforce the ways in which Eleanor Roosevelt brought people together and made them feel seen, heard, and respected. Paper dolls thread through the backgrounds, and Eleanor is often depicted holding hands or connected to the people with whom she is interacting, like one long, human, paper chain. Eleanor Roosevelt’s life work supporting families in under-resourced communities, creating safe working conditions, and promoting world peace has never been more relevant. While we have not lived through the same long-term economic devastation of The Great Depression, the COVID-19 pandemic has created an economic crisis for millions of Americans and billions across the globe. Congress and the White House are engaged in complex conversations and negotiations about the role of government, debating what social programs, safety nets, and infrastructure investments are appropriate in the 21st century; the same kinds of conversations Eleanor Roosevelt engaged in with her husband and their White House staff. The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed how very interconnected our world is, a theme exemplified in the life and work of Eleanor Roosevelt. Using the Investigate, Explore, and Create Model of The Biography Clearinghouse, we offer a range of critical teaching and learning experiences to use with Eleanor Makes Her Mark: How Eleanor Roosevelt Reached Out, Spoke Up, and Changed the World on our site. In our interview with Barbara Kerley and Edwin Fotheringham, you can learn about their research and creating processes. Highlighted here are two ideas inspired by the book. First Ladies and Social Media During our interview, Barb Kerley shared that she found a treasure trove of information about Eleanor Roosevelt’s daily life in archives of Eleanor’s (almost) daily column, “My Day,” which ran in papers across the country from 1935 to 1962. Laughing, Barb suggested that the column was Eleanor Roosevelt’s version of social media. After reading Eleanor Makes Her Mark, leverage Eleanor’s “My Day” column as an opportunity for your middle school students to explore how First Ladies have used the tools at their disposal to communicate directly with the public. To learn more about the column, you can explore the resources of The George Washington University’s Digital Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project. Read her column by year or search for specific content across the years. After students have had an opportunity to read some columns, have them compare and contrast them with one another. What do they learn about Eleanor Roosevelt, and the circumstances of the world she lived in? How do the columns extend the understanding of Eleanor’s public life they received from Eleanor Makes Her Mark? How do they challenge their understanding? Next, provide students with the opportunity to compare and contrast how the current and most recent First Ladies have used social media to speak with the public. Because some comments on social media are not appropriate for tweens to read, we recommend that you select some tweets from each First Lady and share them with your students. You can choose from First Lady Jill Biden’s (@FLOTUS) Twitter account, former First Lady Melania Trump’s (@MELANIATRUMP) Twitter account or her archived @FLOTUS Twitter account, former First Lady Michele Obama’s current (@MichelleObama) Twitter account or her archived @FLOTUS Twitter account, and former First Lady Laura Bush’s current (@laurawbush) Twitter account. Synthesize the exploration by asking students to compare and contrast what they see as most valuable in the communications they explored. Why is it important for First Ladies--or First Gentlemen, or First Spouses--to communicate directly with the public? What kind of information is valuable for them to share, and why? Creating Diagrams to Add Information Writers and artists often choose to represent information visually with a diagram. Ed Fotheringham talked about his process of researching the floorplans of the White House and deciding how to show the inside of the White House. He ultimately settled on a cut-away diagram that is similar to a cross-section diagram. Diana Aston and Sylvia Long also use diagrams masterfully in their informational books An Egg is Quiet (2006) and A Seed is Sleepy (2007). Explore the power of diagrams to carry information with your students.

Visit The Biography Clearinghouse for several more teaching ideas for Eleanor Makes Her Mark and the other biography units we have on the website! Mary Ann Cappiello teaches courses in children’s literature and literacy methods at Lesley University, blogs about teaching with children’s literature at The Classroom Bookshelf, a School Library Journal blog, and is a former chair of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8. Jennifer Sanders is an Associate Professor of Literacy Education at Oklahoma State University, specializing in representations of diversity in children’s and young adult literature and writing pedagogy. She is co-founder and co-chair of The Whippoorwill Book Award for Rural YA Literature and long-time member of CLA. |

Authors:

|

CLA

About CLA

|

Journal of Children's Literature

Write for JCL

|

ResourcesCLA-sponsored NCTE Position Statements

|

Members-Only Content

CLA Video Library

|

© COPYRIGHT 2018.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed