By Jared S. CrossleyAlthough the fight for increased diversity in children’s literature has been going on for decades, there has been a recent surge in attention to this need since 2014 and the creation of the We Need Diverse Books (WNDB) campaign. The website for WNDB states that they advocate for “essential changes in the publishing industry to produce and promote literature that reflects and honors the lives of all young people” (We Need Diverse Books, n.d.), and their definition of diversity extends beyond diversity in sexual orientation, gender, and race, but also includes disability. According to the U.S. Department of Education (2019) there were 7 Million students in 2017-2018 who received special education services, accounting for 14 percent of all public school students. The amount of time these students spend inside a general education classroom has been gradually increasing over the last twenty years. This contributes to the growing need for educators to use texts with positive and accurate disability portrayals as part of their reading instruction in the general education classroom (Collins, Wagner & Meadows, 2018). Children with disabilities need to be able to see themselves in the books they read, and their classmates can also benefit, gaining empathy and understanding, by reading about children with similar disabilities. Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop (1990) wrote about how books can serve as windows, “offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange” (p. 1). They can also serve as mirrors, which reflect our own experiences, and “in that reflection we can see our own lives and experiences as part of the larger human experience” (p. 1). It is very important that all children see themselves reflected in the books they read. However, many children who have disabilities or are racial minorities often don’t see themselves in the books that are available to them. Bishop stated: "When children cannot find themselves reflected in the books they read, or when the images are distorted, negative, or laughable, they learn a powerful lesson about how they are devalued in the society of which they are a part. Our classrooms need to be places where all the children from all the cultures that make up the salad bowl of American society can find their mirrors" -Rudine Sims Bishop Educators should make it a priority to provide all of the children in their classrooms books that serve as mirrors, as well as books that are windows into cultures that are not familiar to their students’ lived experiences. For the past four years, I have been privileged to serve on USBBY’s Outstanding Books for Young People with Disabilities committee. During that time I have gained new perspectives and learned more information about various disabilities and differences. One type of book that often gets grouped into the disability category is books that contain a portrayal of deafness. It has been debated if deafness should be considered a disability (Harvey, 2008; Lane, 2002) with varying opinions for and against the consideration of deafness as a disability. However, regardless of whether or not it is a disability, we need positive portrayals of deafness in children’s literature that can serve as mirrors for children who are deaf, and windows for children who are hearing. Over the past few years there have been a number of excellent middle-grade books that center a child who is deaf. In this post, I want to highlight three titles that I thought were exceptional portrayals.

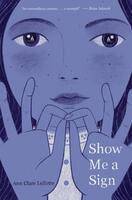

Show Me a Sign

Show Me a Sign by Ann Clare LeZotte (2020) tells the story of Mary, a young girl growing up deaf in the early 1800’s on the island of Martha’s Vineyard. As part of a Deaf colony on the island, Mary has always felt safe and protected. However, all of this is threatened by the appearance of a young scientist who is bound and determined to find the cause of the island’s deafness so he can cure this “infirmity”. Soon Mary finds herself in harm's way as this scientist takes her as a “live specimen” in order to more closely study her deafness. The sequel, Set Me Free, is set to be released September 21, 2021.

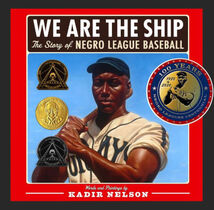

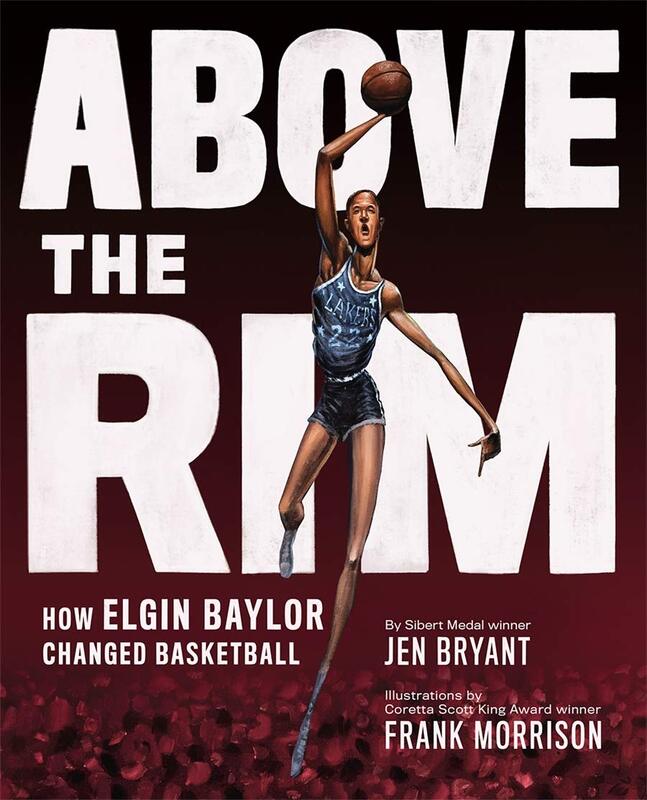

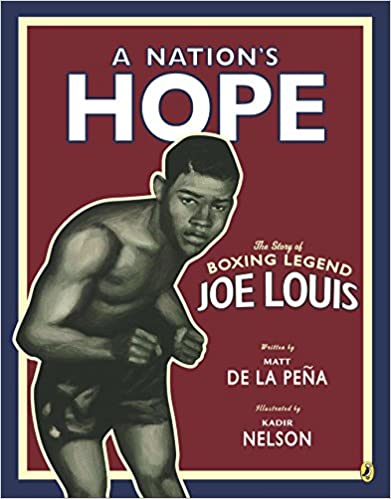

References Bishop, R.S. (1990). Windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 6, ix-xi. Collins, K. M., Wagner, M. O., & Meadows, J. (2018). Every story matters: Disability studies in the literacy classroom. Language Arts, 96(2), 13. Harvey, E. R. (2008). Deafness: A disability or a difference. Health L. & Pol'y, 2, 42. Lane, H. (2002). Do deaf people have a disability?. Sign language studies, 2(4), 356-379. U.S. Department of Education. (2019). Children and youth with disabilities. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgg.asp We Need Diverse Books. (n.d.). About Us. WNDB. Children’s Books Frost, H. (2020). All He Knew. New York, NY: Farrar Straus and Giroux. Kelly, L. (2019). Song for a Whale. New York, NY: Delacorte Press. LeZotte, A.C. (2020). Show Me a Sign. New York, NY: Scholastic Press. Jared S. Crossley is a Ph.D. student at The Ohio State University studying Literature for Children and Young Adults. He is a former 4th- and 5th-grade teacher, and currently teaches children's literature courses at Ohio State. He is the 2020-2021 chair of the Outstanding Books for Young People with Disabilities committee (USBBY). By Patricia E. Bandré Sport has the power to change the world. It has the power to inspire. It has the power to unite people in a way that little else does.”  For approximately four weeks this spring, fourth-grade students at Oakdale Elementary in Salina, Kansas read and discussed, We are the Ship: The Story of Negro League Baseball (Nelson, 2008) as part of a language arts unit. Students found the book highly engaging and the art extraordinary. Numerous discussions occurred as students read, wondered, and conducted research in order to learn more about Negro League players and team owners. Ideas in the book sparked a variety of emotions and prompted numerous conversations about how people treated one another then, how they treat one another today, and what it means to break barriers. When the unit concluded, teachers Joy Fox-Jensen and Mary Plott desired to capitalize on students’ enthusiasm for the book and their interest in sports. They wanted to introduce students to other African American athletes who had broken barriers and pursued their dreams. In my role as the district reading instructional specialist, I worked with the teachers to plan and conduct a six-day mini-unit. We chose four books for our study: Above the Rim: How Elgin Baylor Changed Basketball (Bryant, 2020), Playing to Win: The Story of Althea Gibson (Deans, 2007), A Nation’s Hope: The Story of Boxing Legend Joe Louis (de la Peña, 2011), and Wilma Unlimited: How Wilma Rudolph Became the World’s Fastest Woman (Krull, 1996). We intentionally chose to introduce African American men and women who excelled in sports other than baseball and faced barriers in addition to those posed by race; poverty, illness, and physical disabilities provided further challenges for the athletes we selected. We also wanted students to experience a variety of writing styles and different types of illustrations. Finally, we wished to select athletes to whom the students could connect. We wanted them to see how these barrier-breaking athletes valued determination and perseverance, realized the importance of compassion, and understood how seemingly simple actions spoke louder than words. Our goal was to help the fourth graders begin to see how they could become barrier-breakers, too.  Because students demonstrated such a high level of interest in Kadir Nelson’s paintings when reading We are the Ship, we elected to begin the study with a short exploration of book design. I used information from the article Picturebooks as Aesthetic Objects (Sipe, 2001) to help frame our conversations. We are the Ship (Nelson, 2008), along with two classic picturebooks, Where the Wild Things Are (Sendak, 1963) and The Little House (Burton, 1942), served as models. After reading the two picturebooks aloud, we took a focused look at all three books. As part of our discussion, I prompted students to consider how the size and shape of a book might add to its meaning. Students contemplated the image on the dust jacket and cover of each book – were these images the same or different? Why? They looked closely at the endpapers and wondered about the significance of the colors and the images, if there were any. We considered the color palette each artist used and discussed how those colors suited the text and made them feel. Students noticed the different points of view Nelson employed in We are the Ship; individual players appeared to be larger than life, but in the team paintings, each member seemed equally significant. Students greatly admired Nelson’s full-bleed art, but also found the way Sendak (1963) placed frames around his illustrations in Where the Wild Things Are to be intriguing. Students were quick to notice how the size of the frames changed, disappeared, and reappeared as we watched the main character, Max, journey in and out of his imaginary world. Ultimately, this exploration created a heightened sense of awareness and resulted in careful observations, thoughtful questions, and insightful responses about the other books we read.  Over the next four sessions, students interacted with a new book each day. Each initial reading was conducted as a read-aloud or a combination of listening and partner reading. I purposely did not stop to talk about the book during its first reading. Rather, I wanted students to take in the language and art on their own in order to develop a first draft understanding (Barnhouse and Vinton, 2012). Following this process allowed them to come to their own conclusions about the athletes and the barriers faced without the influence of their peers. Instead of talking, students took two sticky notes and recorded one thing they noticed about the book and one fact they learned during the first read. Students shared their “Notice and Learn” notes with a shoulder partner and posted them for others to read. Next, we dove back into each book and revisited specific passages in order to explore the way the authors used language to provide clues as to the personality of each athlete. An organizer modeled after the Reading with Attitude protocol (Buehl, 2014) assisted to facilitate our conversations. As students reread certain passages from each book, they contemplated the athlete’s and author’s emotions and shared how the text made them feel as the reader. Discussions ensued about the language in the text and how it prompted them to infer the presence of these emotions. Additionally, students made specific references to the art in each book and how it affected their response. As students met each new athlete, the comments they shared made it clear that they realized the athletes were different from one another, but connected by common threads

References

Barnhouse, D., & Vinton, V. (2012). What readers really do: Teaching the process of meaning making. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Buehl, D. (2014). Classroom strategies for interactive learning, (4th ed.). International Reading Association: Newark, DE. Sipe, L. R. (2001). Picturebooks as aesthetic objects. Literacy Teaching and Learning, 6(1), 23-42. Children’s Books

Bryant, J. (2020). Above the rim: How Elgin Baylor changed basketball. Illus. by F. Morrison. Abrams Books for Young Readers: New York, NY. Burton, V. L. (1942). The little house. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. Deans, K. (2007). Playing to win: The story of Althea Gibson. Illus. by E. Brown. Holiday House: New York, NY. de la Peña, M. (2011). A nation’s hope: The story of boxing legend Joe Louis. Illus. by K. Nelson. Dial Books for Young Readers: New York, NY. Krull, K. (1996). Wilma unlimited: How Wilma Rudolph became the world’s fastest woman. Illus. by D. Diaz. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston, MA. Sendak, M. (1963). Where the wild things are. HarperCollins Publishers: New York, NY. Patricia E. Bandré, Ph.D., is the reading instructional specialist for USD 305 Public Schools, Salina, KS and serves as treasurer for CLA. Joy Fox-Jensen and Mary Plott are fourth grade teachers at Oakdale Elementary School, USD 305 Public Schools, Salina, KS. We wish to thank the Salina Education Foundation for funding this project. BY EUN YOUNG YEOM

Using YAL to include emergent bilinguals’ voices

Reading young adult literature (YAL) can be very beneficial for secondary-level students and can operate as a powerful context for discussing complex social issues relevant to students’ lives and current society. Reading and discussing YAL can expand students’ horizons and their conceptions of themselves. The benefits of reading and discussing YAL could also be applied to English learning emergent bilingual adolescents. Recent studies show that leveraging emergent bilinguals’ heritage languages as a scaffold can support English development. However, few educators and researchers discuss how secondary-level emergent bilinguals make sense of the world through reading and discussing YAL written in English, how responding to YAL can be a medium to amplify their voices, and how their heritage languages could be a steppingstone for them to immerse themselves into YAL texts. In many U.S. classrooms that are often dominated by standard English, emergent bilingual adolescents’ perspectives toward YAL and their conceptions of the world can easily be dismissed. One core reason could be that emergent bilinguals’ written and oral utterances, often expressed through developing English mixed with their heritage languages, might look different from standard English expression. However, emergent bilinguals make sense of the world through intermingling their heritage languages and English, a process called translanguaging. Using heritage languages can serve as a bridge for emergent bilinguals to make meaning of YAL texts written in English because translanguaging is a natural way in which bilinguals engage with the world. Through this lens, emergent bilinguals are seen as capable meaning makers with diverse cultural and linguistic repertoires, not as English learners with limited English proficiency who cannot form proper English sentences. Classroom language policy matters Taking advantage of their heritage languages for discussing YAL can open doors for emergent bilingual students to express their opinions easily, and to access their lived experiences and cultural values in relation to the YAL texts they are reading and discussing. For secondary ELA classrooms where many YAL texts are incorporated, allowing emergent bilingual students use of their heritage languages could be a first step toward including more of their voices in discussions. For written responses, opening translanguaging spaces for intermixing heritage languages and English could be another way to honor bilingual students' cultural and linguistic resources and expand their expression options. Ultimately, teachers’ efforts to create a more linguistically inclusive classroom environment can support emergent bilingual students’ active involvement in YAL reading and discussions and can enrich the breadth of ideas and interpretations made available to the classroom community. Teachers’ modeling of blending two languages to make meaning could also reap benefits.

Integrating culturally relevant YAL also matters

In addition to efforts toward linguistic inclusiveness through translanguaging practices, incorporating culturally relevant YAL is equally important. If emergent bilingual students have to sit in a classroom reading a novel written in a second language they have started learning, text analysis will take tremendous energy. If they also have to discuss the novel in the foreign language, they may not be able to fully express their thoughts and feelings, even when formulating insightful ideas in their heads. To make matters worse, if the novel is irrelevant to their lives and cultures, the hardship comes in a combo plate. Incorporating YAL texts that are relevant to emergent bilinguals’ lives is one of the choices teachers can make for emergent bilinguals to feel more included by seeing themselves in the stories they are reading. Emergent bilingual adolescents, who may feel marginalized due to languages, race, and their status as immigrants or refugees, need school to be a space where they feel valued and validated. They are an important part of the colorful fabric of U.S. classrooms, which have increasingly become linguistically diverse. By respecting emergent bilingual adolescents’ bilingual repertoires and honoring their cultural identities through culturally relevant YAL, ELA classrooms can become a welcoming, empowering space for emergent bilingual adolescents to express their feelings, thoughts, and perspectives. RESOURCES

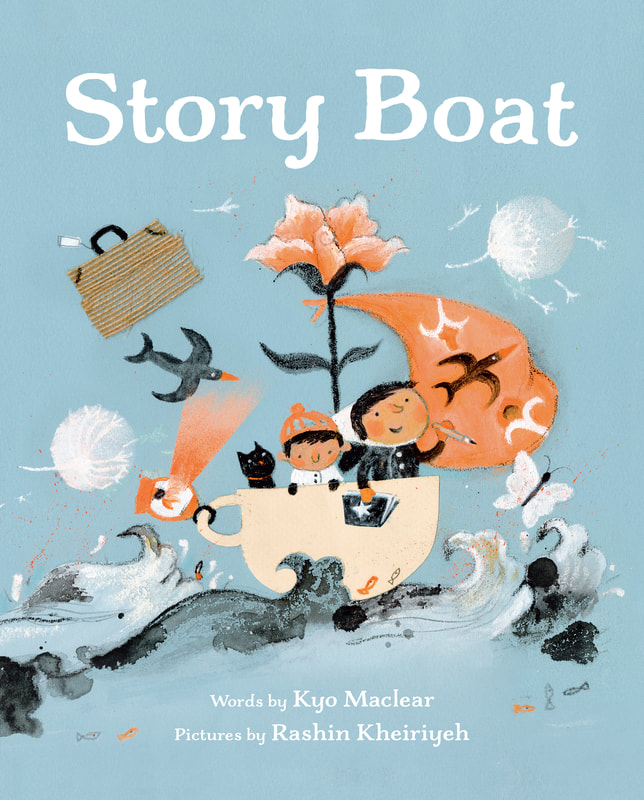

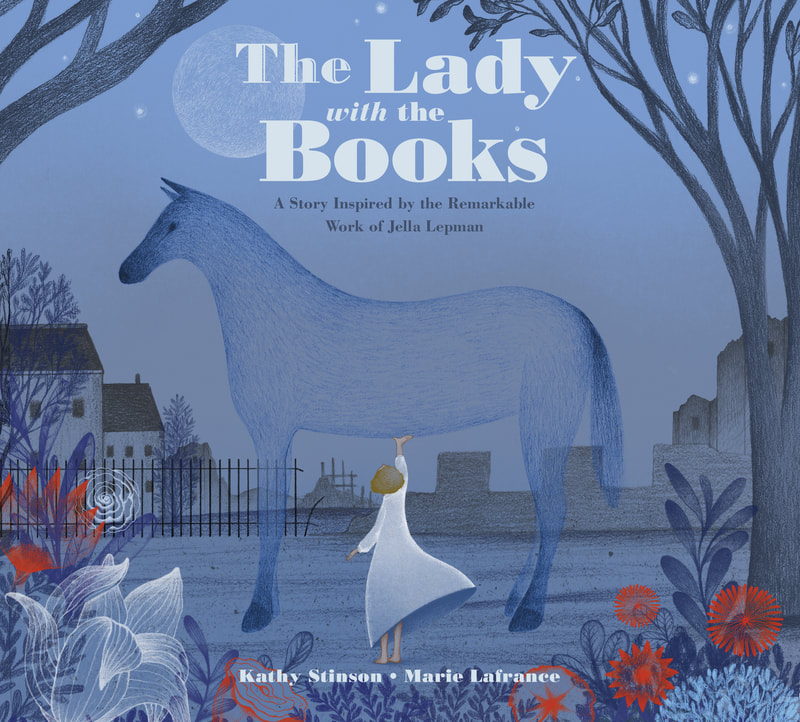

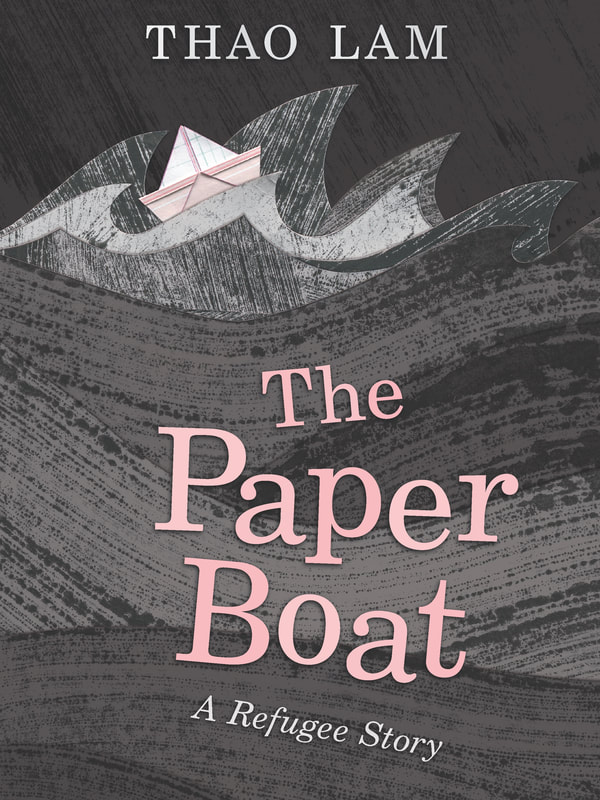

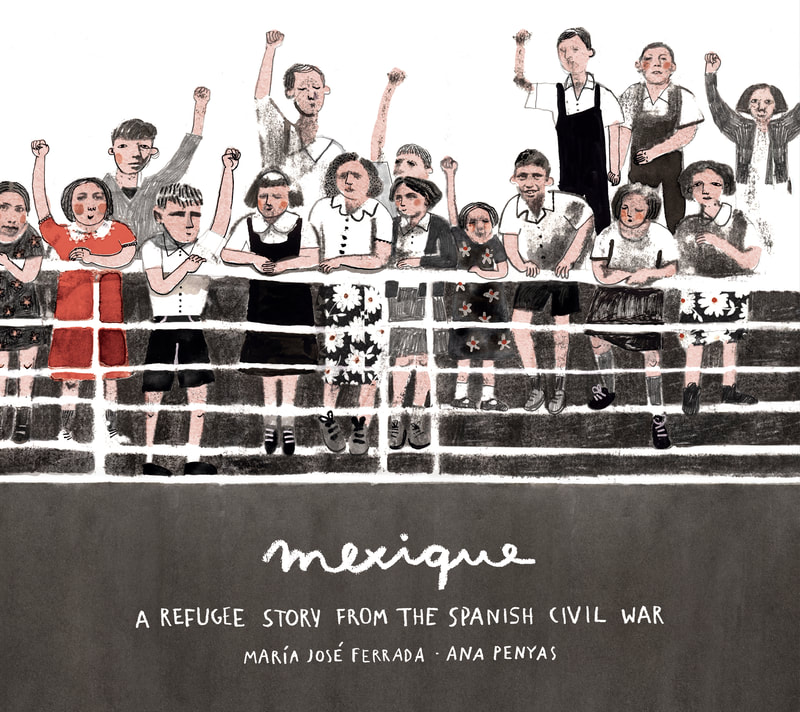

Translanguaging Guides | CUNY-NYSIEB Recommended sites for finding culturally relevant YAL for emergent bilingual adolescents Immigration and refugee experiences:

Asian immigrant experiences:

Latinx immigrant experiences African immigrant experiences: YAL about immigrants from the Middle East or Middle Eastern characters:

Eun Young Yeom was an in-service middle/high school English teacher in South Korea for 12 years, and is a doctoral student in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia. Her research revolves around transnational emergent bilinguals’ language practices and their responses to young adult literature.

Conducting a Writing Cohort with the Support of the Bonnie Campbell Hill AwardBY KATIE SCHRODT

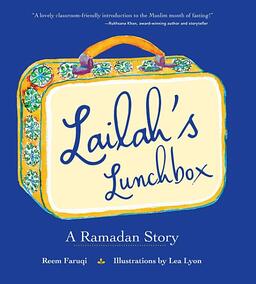

CLA Blog: Knowledge is Power: Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors BY MELISSA ANTINOFF  I was honored to be named one of the 2020 Bonnie Campbell Hill National Literacy Leader Award recipients. My project was to continue my equity work as a literacy leader. It is imperative that every classroom in every school district has books with BIPOC characters by BIPOC authors. Students need to see themselves in books (like a mirror) and see the rest of the world as well (like looking out a window). Books are the perfect gateway for this (like a sliding glass door that automatically opens and invites you in). While I have learned so much from the conferences I have attended so far this year, the most important piece of knowledge I’ve gained is that my equity work has spread from my school to my community. I now have language to teach my friends and family how to advocate for BIPOC and LGBTQ+ communities. Recently, the fervor over Dr. Seuss Enterprises no longer publishing 6 books with racist imagery was all over my social media feeds. I was shocked and disappointed by friends that thought the company was “going overboard.” One friend even said, “If you don’t like it, don’t buy it.” I replied with pictures of the offensive illustrations by Seuss, explaining why those 6 books were no longer going to be published. I used the analogy of windows. mirrors, and sliding glass doors to explain how none of those pictures have a place in our society. As librarian Leslie Edwards said, “A book published in 1937 with images that are considered racist by the group publishing the book...doesn't have a place in an elementary classroom or school library in 2021. Nostalgia isn't a reason for keeping a book. In schools and school libraries, the collection should reflect diverse viewpoints in an age- and developmentally appropriate manner. These diverse viewpoints should not demean or diminish others.” Some of my colleagues refuse to even touch the subject of racism and prejudice with their students, much less have diverse books in their classroom libraries. Last year, when I used our language arts budget for diverse books for each of my grade level’s classroom libraries, a colleague told me that the money was better spent on other materials. After attending my workshop on Culturally Responsive Teaching Through Diverse Literature, she changed her mind. She now could now understand the importance of a diverse library and how it will help her reach all of her students. I recently read aloud Lailah’s Luncbox, by Reem Faruqi. It’s a book about a girl fasting for Ramadan. I have a Muslim student in my third grade class that fasts. The other students now have an appreciation for her culture and she was so happy to share her knowledge with her classmates. Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. With all of this professional and personal development, I now have the language and knowledge to change people’s minds. My students, colleagues, and community do, too. Katie Schrodt is a professor of literacy at Middle Tennessee State University where she works with pre-service and serving teachers. Katie’s research interests include reading and writing motivation with young children. She is one of the 2020 Bonnie Campbell Hill Award recipients. Melissa Antinoff is the 2019 Burlington County Teacher of the Year. She has been an elementary educator since 1992. Melissa specializes in developing a love of reading in her students. Planting Seeds for Professional Involvement with Bonnie Campbell Hill BY KATHRYN WILL 2018 NCTE Annual Convention, Houston 2018 NCTE Annual Convention, Houston Winning the 2018 Bonnie Campbell Hill National Literacy Leader Award for my clinical work with preservice teachers in our local schools allowed me to support the attendance of two university students, Emily and Allicia, at the 2018 NCTE conference in Houston. They were astounded by the warm welcome they received at the CLA breakfast that year, the sessions they attended, and of course the free books signed by authors. To say they were gobsmacked would be accurate. Upon our return from the conference, they shared their experience in a student gathering on campus with others where it was well received and created a buzz in the teacher education program for quite a time afterwards. They graduated in the Spring of 2019, accepting their first teaching positions in nearby schools. Because of the positive experience they had at the 2018 conference, they attended NCTE 2019 in Baltimore as seasoned conference attendees, focusing in on their current classroom needs and of course gathering books for their classroom libraries. After starting a YA book club in the summer of 2019, we continued to meet together virtually throughout the pandemic--sometimes for our book club that grew out of the initial NCTE experience, and other times to navigate classroom or learner challenges. When we met a few weeks ago, I asked them about the initial experience of attending NCTE with me. Emily commented that the experience opened her eyes to the importance of making connections within the profession at a national level. Allicia added that she never would have considered going to something like NCTE if she had not gone with me. It made her dream bigger as a teacher and as a person. They both agreed they will attend again. I am so grateful that winning this award allowed me to plant and nurture the seeds of professional involvement for these teachers in the early stages of their careers. I hope there are opportunities for me to continue this in the future with other preservice teachers. Catching Up with Quintin: A Bonnie Campbell Hill Literacy Leader Award Update BY QUINTIN BOSTIC  Kathryn Will (left) & Quintin Bostic (right) Kathryn Will (left) & Quintin Bostic (right) When he won the award in 2018, Quintin was preparing to teach his first course in elementary writing instruction for undergraduate preservice teachers. Although his time in the Ph.D. program is coming to an end, the doors to opportunities are just beginning to open. Shortly after receiving the Bonnie Campbell Hill Literacy Leader Award, Quintin began to implement his PLC series. The 3-day series supported teacher trainers and teachers in using various strategies to have critical conversations with students through picture books in their classrooms. The professional development program addressed topics like #BlackLivesMatter, LGBTQIA+ families, multilingualism, varying abilities, and more. Attendees of the professional development supported students from preschool to third grade in an inner-city school district in Atlanta, Georgia. A major highlight from the project was that because it was so well received, the project was further funded through a local agency for the continued support of teachers in the local area. Through the Bonnie Campbell Hill Literacy Leader Award, not only was Quintin able to implement the PLC series, but he was also able to attend the annual convention of the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) in Houston, Texas in 2018, attend the Children’s Literature Assembly’s breakfast, and attend the all-attendee event that featured author Sharon Draper. Because of the award, Quintin has gained a platform that has helped him to continue to advance in his academic career.  Quintin Bostic Quintin Bostic Quintin is currently wrapping up his Ph.D. in Early Childhood and Elementary Education at Georgia State University. His research focuses on how race, racism, and power are communicated through the text and visual imagery in children’s picturebooks. Additionally, in 2020, Quintin was named co-chair of the National Association for Professional Development Schools (NAPDS) Anti-Racism Committee. The association – which provides professional development, advocacy, and support for school-university partnerships – first established the Anti-Racism Committee in response to racial violence in 2020. As co-chair, Bostic will work to foster a culture of equity and inclusion within the association, and in the communities it supports; create and implement anti-racist policies, practices, and systems; and recommend and implement tools and approaches for continued reflection and progress. “Our goal is to address racism by providing teachers and community partners with the necessary resources to do so,” Bostic said. “These resources vary, ranging from trainings to resources, that can help challenge and overcome racist ideologies that are embedded throughout society.” He also just started a new career with Teaching Lab, in which is serves as a Partnerships Manager. Quintin is beyond thankful to Bonnie Campbell Hill, her family, the Children’s Literature Assembly, and everyone who makes this award possible. “There are so many people, like me, who would have never had the opportunity to have so many experiences without the support, love and care of people like the Bonnie Campbell Hill Award family. I am so appreciative, and I look forward to seeing what amazing things will come out of this award in the future.” Kathryn Will is an Assistant Professor of Literacy at the University of Maine Farmington (@KWsLitCrew). She is passionate about sharing the power of children's literature with her students. She is one of the 2018 Bonnie Campbell Hill Award recipients, a member of the 2019 Notables Committee, and current chair of the Notables Committee.

Quintin Bostic is a Ph.D. Candidate at Georgia State University. He is also Partnerships Manager at Teaching Lab and co-Chair of the NAPDS Antiracism Committee. His personal website is https://drquintinbostic.com. Editorial Note: Check out our April 6 Post about the Bonnie Campbell Hill Literacy Leader award and look out for another award recipient update post next week. If you are interested in applying for this year's award, visit the Bonnie Campbell Hill Literacy Leader Award page for the application details. BY DONNA SABIS-BURNS

We are obligated to educate our youth with a clear lens and to teach the richness of realistic, authentic, and contemporary literature for children and young adults. We need to promote books where Indigenous characters are up front and visible, not hidden or pushed aside. We want to highlight in a bold, distinguishable manner characters and stories that unveil and promote the beauty of diverse literature written/illustrated by and for Native Nations (also called Indigenous people and used interchangeably here when the specific Nation is not known), and all other marginalized groups.

The movements of #OwnVoices and #WeNeedDiverseBooks have elevated the bar by offering a deeper focus and expanded landscape for celebrating the intricacies that Native storytelling brings to the table. Much too often, books featuring Indigenous people are only pulled off the shelf in October (Columbus) and November (Thanksgiving/Native Heritage Month). Well, it is March/April and I am pleased to share with you some resources you may want to check out and bookmark this spring to break that cycle. This blog post features a few rich and informative web pages, the American Indian Literature Awards (AILA), a shout out to an award-winning #OwnVoices book, and other informative and fun resources that highlight the resilience, authenticity, and beauty in literature through a kaleidoscope of traditions representative of the vast diversity across Indian Country. Native Cultural LinksHeartdrum

What is impressive about this site is its refreshing approach to much-needed stories about Indigenous, contemporary young heroes and heroines. These heartfelt accounts are reflective of the many different Nations of a modern United States and Canada. This is a breath of fresh air because it does not perpetuate the notion that Indigenous peoples are not around anymore. Do not get me wrong, there is a definite need for authentic, truthful history stories of Native Nations, but it is truly wonderful to be able to share a good story about real time people in real time situations in a modern setting. This is a new resource that is just getting off the ground and it already has some exquisite stories to share with you.

Oyate

Oyate.org is a small but mighty Indigenous organization working to share the life and histories of Indigenous people with the utmost level of honesty and integrity. This is a resource that serves as a portal into the past and is reflective of today’s society where diverse, #ownvoices books are most necessary. Oyate, appropriately named after the Dakota word for “people,” believes that the world is a healthier place when there is a better understanding and respect for one another and when history is truthfully acknowledged. They aim to distribute literature and learning materials by Indigenous authors and illustrators, provide critical evaluation of books and curricula with Indigenous themes, and offer workshops “Teaching Respect for Native Peoples.” They also have a small resource center and reference library that can be very useful for any educator or parent (or youth for that matter). Since the pandemic, the store portion of the site is temporarily not working at full capacity, but there are many other fine choices for you to peruse and enjoy.

American Indians in Children’s Literature

We cannot mention websites about literature featuring Indigenous people without showcasing the American Indians in Literature (AICL) website. Established by Dr. Debbie Reese of Nambé Pueblo, and later joined by Dr. Jean Mendoza as co-editor, the AICL website provides a critical analysis of the presence of Indigenous peoples in children's and young adult books and so much more. This website is like walking into a bakery with so many wonderful choices it is hard to decide what to try first. It has been around for 15 years and is most certainly more than just a place to find a list of best books. You can discover Indigenous authors and illustrators in the Photo Gallery section, or maybe you’d rather learn tips for creating instructional materials featuring different Native nations. You can even research what books you should NOT be sharing out there. It is really a gem of a resource.

Book Award

AILA Youth Literature Award

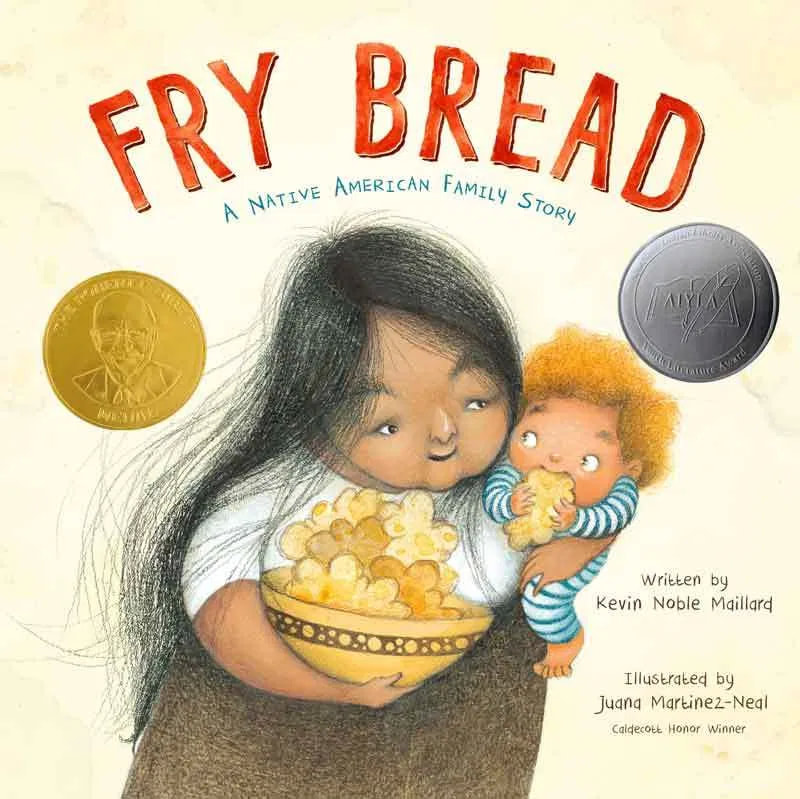

Did you know there is an award specifically for literature featuring Indigenous people? Since 2006, the American Indian Library Association (AILA) biennially considers the finest writing and illustrations by Indigenous peoples of North America for the AILA Youth Literature Award. AILA identifies and honors works that “present Indigenous North American peoples in the fullness of their humanity.” Winners and Honor Books are selected in the categories: Best Picture Book, Best Middle Grade Book, and Best Young Adult Book. If you ever need a resource for choosing quality literature, make sure you visit the American Indian Youth Literature Award web page. For those not familiar with this organization, AILA is an affiliate of the American Library Association and it is devoted to disseminating information about Indigenous cultures and languages to the library community and beyond. Check out the video for the 2020 Award winners. Did you know?

Caldecott Winner

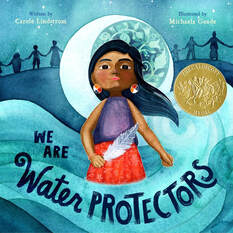

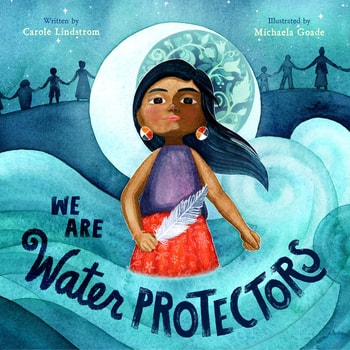

Congratulations to illustrator Michaela Goade (Tlingit) for her 2021 Caldecott Award winning book, We are Water Protectors (2020), authored by Carole Lindstrom (Turtle Mountain Band of Ojibwe). Goade is the very first Indigenous winner of this prestigious award. With Earth Day around the corner, this would be a fabulous book to share. There is even a We are Water Protectors Activity Kit!

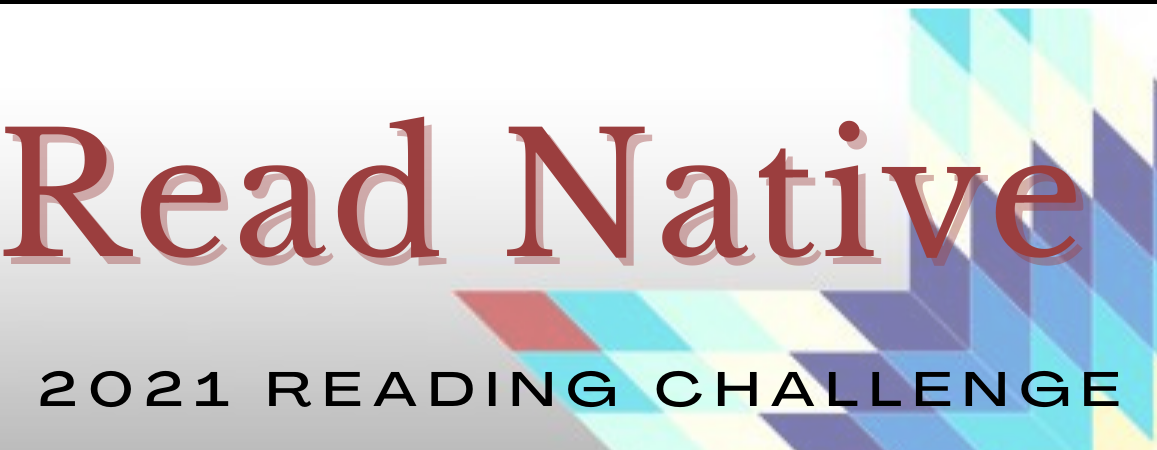

Read Native 2021 Reading Challenge

The “American Indian Library Association invites you to participate in the inaugural reading challenge. With this challenge we support and recognize our Indigenous authors, scientists, legislators, storytellers, and creators throughout the year, not just during the national Native American Heritage month.” Here is a fun reading challenge to engage readers of all ages. Final Words

Throughout the year, find and read books and publications by and about Native Americans; visit tribal websites; search peer reviewed scholarly journals; visit Native-owned bookstores; and check with Native librarians for the best sources for learning more about Native Nations and Indigenous people around the world.

Donna Sabis-Burns, Ph.D., an enrolled citizen of the Upper Mohawk-Turtle Clan, is a Group Leader in the Office of Indian Education at the U.S. Department of Education* in Washington, D.C. She is a Board Member (2020-2022) with the Children's Literature Assembly, Co-Chair of the 2021 CLA Breakfast meeting (NCTE), and Co-Chair of the Diversity, Equity and Inclusivity Committee at CLA.

*The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the positions or policies of the U.S. Department of Education. No official endorsement by the U.S. Department of Education of any product, commodity, service, or enterprise mentioned herein is intended or should be inferred.

BY JENNIFER M. GRAFF AND BETTIE PARSONS BARGER “The stories you read can transform you. They can help you imagine beyond yourself. When you read a great story you leave home. We leave home to find home.”

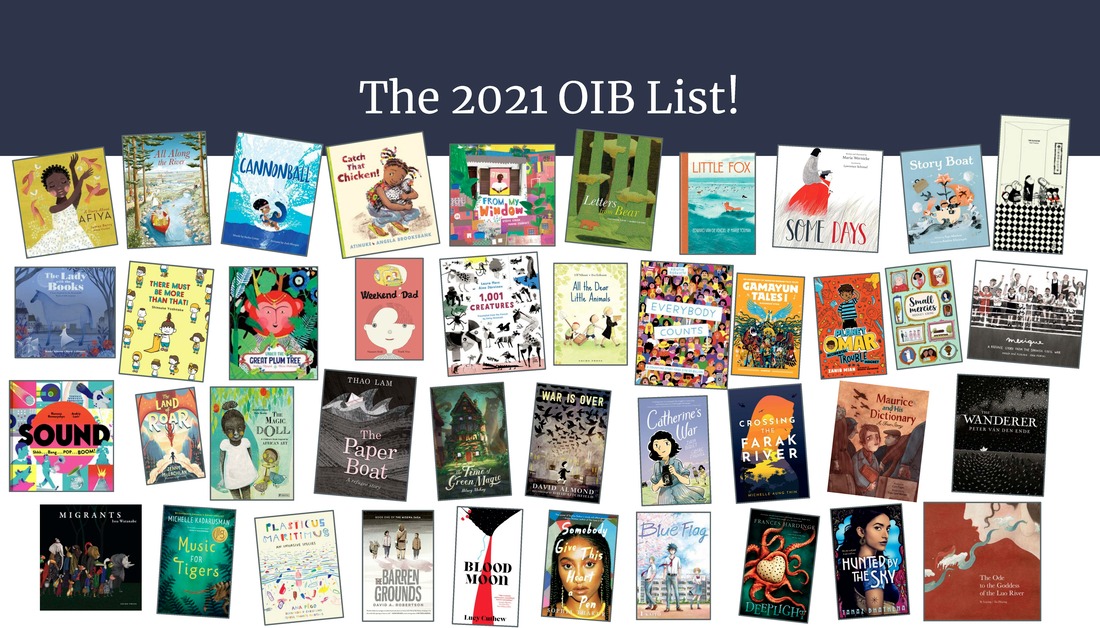

(Rochman & McCampbell, 1997, p. vii) The COVID-19 Pandemic has significantly shifted global travel to “zooming” from digital screen to digital screen and surfing online streaming services. For those fatigued by such excursions, international children’s books can offer exciting and thought-provoking adventures of the heart, mind, spirit, and global consciousness. Readers can enter fantastic worlds, hear previously unheard voices and perspectives, learn more about scientific worlds and cultural communities, and become immersed in emotional episodes that speak to senses of humanity and belonging in books published on multiple continents. The United States Board on Books for Young People (USBBY)’s annual Outstanding International Books (OIB) list is a great go-to guide for such literary experiences. As mentioned in Wendy Stephens’ overview of youth literature awards and described by USBBY President, Evie Freeman, the OIB list provides readers of all ages--especially educators and readers in grades PreK-12--a collection of 40-42 books originally published outside of the United States (U.S.) that are now available in the U.S. These books, selected by a committee of teachers, librarians, children’s literature and literacy education teacher educators and scholars, connect us to noteworthy international authors and illustrators who seek to entertain, inform, challenge, delight, stimulate, and unite people through story.

Engaging with the 2021 OIB List: A Geographical Map and Themed Text Sets  Even with the grade-level band organization of the OIB list, selecting which books to read might feel daunting. Two ways to help facilitate book selections are the Interactive Google Map and thematic text sets. Each OIB list has its own interactive Google Map, illustrating the international communities represented by the selected books. Using the color-coded pins on the world map or the left sidebar, select a book to zoom in on its location. Additional uses of the maps include critical analyses and discussions about dominant/absent voices, cultural representations, and equity on a global scale. The 2021 OIB books also fit within text sets conducive to interdisciplinary and socioemotional learning as well as differentiated instruction. The table below includes the 35 OIB titles identified for PreK-8 grades organized into five themes. While each book is mentioned once, many could fit into multiple themes. The variety of genres, formats, and cultural origins reminds us that storytelling and humanity have no borders and amplifies the connections and intersections of self and society. Visit the USBBY OIB website or the February issue of the School Library Journal for all of the book annotations.

References Rochman, H., & McCampbell, D. Z. (1997). Leaving home. HarperCollins Children’s Literature References The OIB 2021 Bookmark has bibliographic information for the aforementioned books. Jennifer M. Graff is an Associate Professor in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia, is a former CLA President and has been a CLA Member for 15+ years. Bettie Parsons Barger is an Associate Professor in the Department of Curriculum and Pedagogy at Winthrop University and has been a CLA Member for 10+ years. BY WENDY STEPHENSEditorial Note: This post is the first in a 2-part series by Wendy Stephens discussing the rich landscape of book awards announced over the winter months. In this first post, Wendy focuses on ALSC awards and awards by ALA affiliates recognizing books for children or books for a wide spectrum of age groups. The second post, which will be published next week, will present awards for YA literature administered by YALSA, as well as several other notable awards. When we talk about budgeting for materials, I always advise my school librarian candidates to be sure to save some funding for January. No matter how good their ongoing collection development has been throughout the year, there are always some surprises when the American Library Association's Youth Media Awards (YMAs) roll around, and they'll want to be able to share the latest and best in children's literature with their readers. These are the books that will keep their collections up-to-date and relevant. From our own childhoods, we always remember the "books with the medals" -- particularly the John Newbery for the most outstanding contribution to children's literature and the Randolph Caldecott for the most distinguished American picture book for children. These books become must-buys and remain touchstones for young readers. In 2021, Newbery is celebrating its one hundredth year. Some past winners and honor books are very much a product of their time, and many of those once held in high esteem lack appeal today. For those of us working with children and with children's literature, the new books honored at Midwinter offer opportunities to revisit curriculum, update mentor texts, and build Lesesneian "reading ladders." Each award committee has its own particular award criteria and guidelines for eligibility, and its own process and confidentiality norms. Every year, the YMAs seems to be peppered with small surprises. Does New Kid winning the Newbery means graphic novels are finally canonical? Is Neil Gaiman an American? What about all the 2015 Caldecott honors, including the controversial That One Summer? Did the Newbery designation of The Last Stop on Market Street mean you can validate using picture books with older students? How does Cozbi A. Cabrera's much-honored art work resonate at this historical moment? In Horn Book and School Library Journal, Newbery, Caldecott and Printz contenders are tracked throughout the year in blogs like Someday My Printz Will Come, Heavy Medal, and Calling Caldecott. Other independent sites like Guessing Geisel, founded by Amy Seto Forrester are equally devoted to award prediction. Among librarians and readers, there are lots of armchair quarterbacks, and conducting mock Newbery and Caldecotts, either among groups of professionals or with children, have become almost a cottage industry. There are numerous how-tos on that subject, from reputable sources like The Nerdy Book Club and BookPage. But there are numerous other awards announced at ALA Midwinter almost simultaneously that deserve your attention, too. Among the Association for Library Services for Children (ALSC) awards are: the Robert F. Sibert Medal, the Mildred L. Batchelder Award, the Geisel Award, the Excellence in Early Learning Digital Media Award, and the Children's Literature Legacy Award.

Aside from the award winners, each year annual ALSC Children's Notable Lists are produced in categories for Notable Children's Recordings, Notable Children's Digital Media, and Notable Children's Books. If you want to see the machinations behind the designation, those discussions are open to the public this year via virtual meeting links. Outside of ALSC, many of ALA’s affiliates have their own honors for children's literature. These include the Ethnic and Multicultural Information Exchange Round Table (EMIERT) which sponsors the Coretta Scott King Book Awards; the Association of Jewish Libraries which sponsors the Sydney Taylor Book Awards; and REFORMA: The National Association to Promote Library and Information Services to Latinos and the Spanish-Speaking which sponsors the Pura Belpré awards. In addition to these affiliates, others such as the Asian/Pacific American Librarian Association and the American Indian Library Association also present awards. The awards are always evolving to reflect the abundance of literature available for young people. Like the Association of Jewish Libraries and the Asian/Pacific American Librarian Association awards, the American Indian Youth Literature Awards were first added to the televised YMA event in 2018. And this year was the first year for inclusion for a new Young Adult category for the Pura Belpré. Two awards of particular significance are the Stonewall Book Award – Mike Morgan and Larry Romans Children’s and Young Adult Literature Awards are given annually to English-language works found to be of exceptional merit for children or teens relating to the gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender experience, and the Schneider Family Book Awards, honoring authors or illustrators for the artistic expression of the disability experience for child and adolescent audiences, with recipients in three categories: younger children, middle grades, and teens.

Wendy Stephens is an Assistant Professor and the Library Media Program Chair at Jacksonville State University. BY MEGAN VAN DEVENTERAs educators, we recognize the value in providing readers with reading experiences that act as mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors (Bishop, 1990) to affirm readers’ identities, build empathy for others, and explore humanity. We understand the importance of curating bookshelves that offer a vast array of experiences that validate readers’ lives, feelings, and identities. At times, it can be challenging to select and teach books that do not ‘mirror’ our own lived experience, and it can feel vulnerable to step outside our own expertise. Fortunately, there are many of us committed to expanding our own readership and curating inclusive bookshelves and curricula that resonate with our students. This blog post champions and supports educators doing this vulnerable work to ensure all students are included and reflected and refracted on their bookshelves and in their curricula. This post shares books, tools, and resources to support educators building their expertise to ensure young readers have access to high quality, validating, and accurate children’s literature. Tools and Resources for Curating an Inclusive Bookshelf and CurriculumEducators committed to expanding our bookshelves beyond our own favorite reads must be intentional in selecting and teaching high quality children’s literature that is accurate, validating, and honest. There are several wonderful tools and resources to ensure our bookshelves are inclusive, relevant, and accessible for readers. The four tools and resources below support educators in curating inclusive bookshelves and reading curricula (and help us cull problematic books from our shelves as well).

Books for Curating Inclusive Bookshelves and CurriculaThe tools and resources described above support educators in selecting and teaching high-quality, accurate, and honest children’s literature. Building our expertise through these tools and resources sustains our commitment to curating inclusive bookshelves. Here are four children’s literature books that support educators in holding space that honors young readers’ and teachers’ capacity to engage with complex and authentic picturebooks.

Bookshelves and curricula that honor young readers in helping them make sense of the world are a key aspect to orchestrating equitable and socially just classrooms. These books, tools, and resources support our work as educators in curating high-quality reading experiences that are inclusive, accurate, and honest. ReferencesBishop, R.S. (1990). Windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and using books for the classroom, 6(3), 1-2. Eland, E. (2019). When sadness is at your door. Random House. Lindstrom, C. (2020). We are water protectors. Roaring Brook Press. Muhammad, I., & Ali, S.K. (2019). The proudest blue: A story of hijab and family. Little, Brown and Company. Sanna, F. (2016). The journey. Flying Eye Books.

BY MARY ANN CAPPIELLO on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse As we approach the final quarter of 2020, fires rage along the West Coast. Many regions of the United States face drought conditions. Gulf communities are inundated by Hurricane Sally while a string of storms line up in the Atlantic, waiting their turn. The impact of climate change is evident. COVID-19 continues to wreak havoc on our lives, our health. We bear witness to the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on minoritized groups, including Black and Latinx communities, Native Americans, and the elderly. Across America, Black Lives Matter protests carry on, demanding that our nation invest in the essential work necessary to achieve a more perfect union through racial justice. In 2020, we remember moments of historic change, commemorating the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act and the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment.  The intensity of this moment can’t be denied. It’s demanding. It’s exhausting. Whether you are a teacher, librarian, or university faculty member, you are likely teaching in multiple new formats and modalities, facing daily logistical challenges. Caregivers also face new hurdles in supporting young people’s learning. How do you meet the needs of students and the needs of this moment in history? How do you find hope in literature? Perhaps one way is to turn to the people of the past and the present who are working on the edges of scientific knowledge. Or, to turn to the people of the past and the present who have acted as champions of social justice. Their life stories offer young people models of agency and action, blueprints for change. To that end, The Biography Clearinghouse shares 20 biographies for 2020, a list of recent picturebook and collected biographies to connect with the challenges of the moment. This list is not comprehensive. It is simply a starting place. We hope these recently published biographies of diverse changemakers can become part of your curriculum or part of your read aloud calendar, in-person or over video conferencing software. Biographies About ScientistsBiographies About Champions for Change

If you have any picture book or chapter-length biographies or collected biographies for young people that you would like to recommend, please email us at [email protected]. We’re also interested in hearing more about how you’re using life stories in the classroom this year. Mary Ann Cappiello teaches courses in children’s literature and literacy methods at Lesley University, blogs about teaching with children’s literature at The Classroom Bookshelf, a School Library Journal blog, and is a former chair of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8. |

Authors:

|

CLA

About CLA

|

Journal of Children's Literature

Write for JCL

|

ResourcesCLA-sponsored NCTE Position Statements

|

Members-Only Content

CLA Video Library

|

© COPYRIGHT 2018.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed