Planting Seeds for Professional Involvement with Bonnie Campbell Hill BY KATHRYN WILL 2018 NCTE Annual Convention, Houston 2018 NCTE Annual Convention, Houston Winning the 2018 Bonnie Campbell Hill National Literacy Leader Award for my clinical work with preservice teachers in our local schools allowed me to support the attendance of two university students, Emily and Allicia, at the 2018 NCTE conference in Houston. They were astounded by the warm welcome they received at the CLA breakfast that year, the sessions they attended, and of course the free books signed by authors. To say they were gobsmacked would be accurate. Upon our return from the conference, they shared their experience in a student gathering on campus with others where it was well received and created a buzz in the teacher education program for quite a time afterwards. They graduated in the Spring of 2019, accepting their first teaching positions in nearby schools. Because of the positive experience they had at the 2018 conference, they attended NCTE 2019 in Baltimore as seasoned conference attendees, focusing in on their current classroom needs and of course gathering books for their classroom libraries. After starting a YA book club in the summer of 2019, we continued to meet together virtually throughout the pandemic--sometimes for our book club that grew out of the initial NCTE experience, and other times to navigate classroom or learner challenges. When we met a few weeks ago, I asked them about the initial experience of attending NCTE with me. Emily commented that the experience opened her eyes to the importance of making connections within the profession at a national level. Allicia added that she never would have considered going to something like NCTE if she had not gone with me. It made her dream bigger as a teacher and as a person. They both agreed they will attend again. I am so grateful that winning this award allowed me to plant and nurture the seeds of professional involvement for these teachers in the early stages of their careers. I hope there are opportunities for me to continue this in the future with other preservice teachers. Catching Up with Quintin: A Bonnie Campbell Hill Literacy Leader Award Update BY QUINTIN BOSTIC  Kathryn Will (left) & Quintin Bostic (right) Kathryn Will (left) & Quintin Bostic (right) When he won the award in 2018, Quintin was preparing to teach his first course in elementary writing instruction for undergraduate preservice teachers. Although his time in the Ph.D. program is coming to an end, the doors to opportunities are just beginning to open. Shortly after receiving the Bonnie Campbell Hill Literacy Leader Award, Quintin began to implement his PLC series. The 3-day series supported teacher trainers and teachers in using various strategies to have critical conversations with students through picture books in their classrooms. The professional development program addressed topics like #BlackLivesMatter, LGBTQIA+ families, multilingualism, varying abilities, and more. Attendees of the professional development supported students from preschool to third grade in an inner-city school district in Atlanta, Georgia. A major highlight from the project was that because it was so well received, the project was further funded through a local agency for the continued support of teachers in the local area. Through the Bonnie Campbell Hill Literacy Leader Award, not only was Quintin able to implement the PLC series, but he was also able to attend the annual convention of the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) in Houston, Texas in 2018, attend the Children’s Literature Assembly’s breakfast, and attend the all-attendee event that featured author Sharon Draper. Because of the award, Quintin has gained a platform that has helped him to continue to advance in his academic career.  Quintin Bostic Quintin Bostic Quintin is currently wrapping up his Ph.D. in Early Childhood and Elementary Education at Georgia State University. His research focuses on how race, racism, and power are communicated through the text and visual imagery in children’s picturebooks. Additionally, in 2020, Quintin was named co-chair of the National Association for Professional Development Schools (NAPDS) Anti-Racism Committee. The association – which provides professional development, advocacy, and support for school-university partnerships – first established the Anti-Racism Committee in response to racial violence in 2020. As co-chair, Bostic will work to foster a culture of equity and inclusion within the association, and in the communities it supports; create and implement anti-racist policies, practices, and systems; and recommend and implement tools and approaches for continued reflection and progress. “Our goal is to address racism by providing teachers and community partners with the necessary resources to do so,” Bostic said. “These resources vary, ranging from trainings to resources, that can help challenge and overcome racist ideologies that are embedded throughout society.” He also just started a new career with Teaching Lab, in which is serves as a Partnerships Manager. Quintin is beyond thankful to Bonnie Campbell Hill, her family, the Children’s Literature Assembly, and everyone who makes this award possible. “There are so many people, like me, who would have never had the opportunity to have so many experiences without the support, love and care of people like the Bonnie Campbell Hill Award family. I am so appreciative, and I look forward to seeing what amazing things will come out of this award in the future.” Kathryn Will is an Assistant Professor of Literacy at the University of Maine Farmington (@KWsLitCrew). She is passionate about sharing the power of children's literature with her students. She is one of the 2018 Bonnie Campbell Hill Award recipients, a member of the 2019 Notables Committee, and current chair of the Notables Committee.

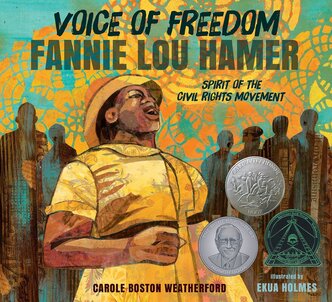

Quintin Bostic is a Ph.D. Candidate at Georgia State University. He is also Partnerships Manager at Teaching Lab and co-Chair of the NAPDS Antiracism Committee. His personal website is https://drquintinbostic.com. Editorial Note: Check out our April 6 Post about the Bonnie Campbell Hill Literacy Leader award and look out for another award recipient update post next week. If you are interested in applying for this year's award, visit the Bonnie Campbell Hill Literacy Leader Award page for the application details. BY JENNIFER M. GRAFF & JOYCE BALCOS BUTLER, ON BEHALF OF THE BIOGRAPHY CLEARINGHOUSE Our current celebration of poetry as a powerful cultural artifact and the national dialogue about voting rights generated by the introduction of 300+ legislative voting-restriction and 800+ voting-expansion bills in 47 states have inspired a rereading of the evocative, award-winning picturebook biography, Voice of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hamer, Spirit of the Civil Rights Movement. Written by Carole Boston Weatherford, illustrated by Ekua Holmes, and published by Candlewick Press in 2015, Voice of Freedom offers a vivid portrait of the life and legacy of civil rights activist, Fannie Lou Hamer. Her famous statement, “All my life I’ve been sick and tired. Now I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired” (p.18) serves as a testimonial to the psychological and physiological effects of the injustices and violence inflicted upon Hamer and other Black community members in Mississippi. Additionally, Hamer’s statement signifies her tenacity, conviction, and unwavering fight for voting rights, congressional representation, and other critical components of racial equality until her death in 1977.

Below we feature one of two time-gradated teaching recommendations included in the Create section of the Voice of Freedom book entry. Youth As Agents of Change in Local CommunitiesWeatherford begins Voice of Freedom with Hamer’s own words: “The truest thing that we have in this country at this time is little children . . . . If they think you’ve made a mistake, kids speak out.” Pairing Hamer’s advocacy detailed in Voice of Freedom with contemporary youth activists, guide students in their exploration of how they can (or continue to) be agents of change in their communities.

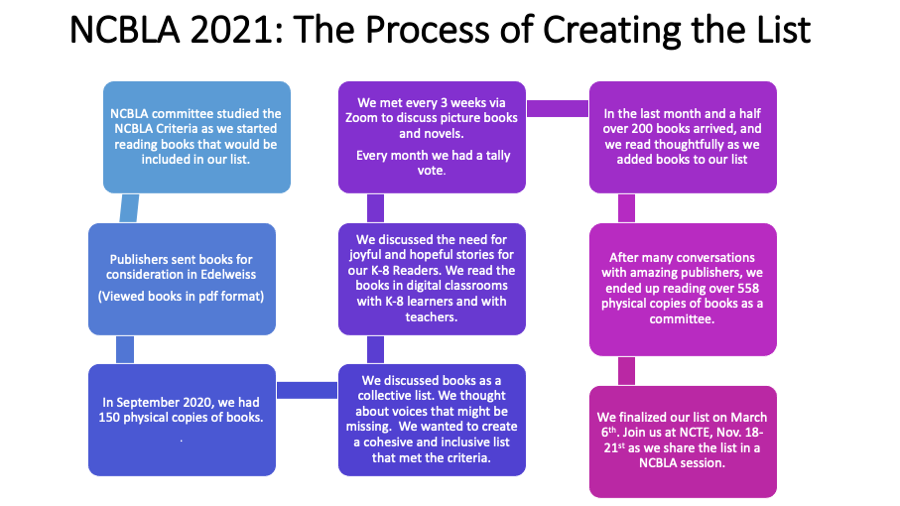

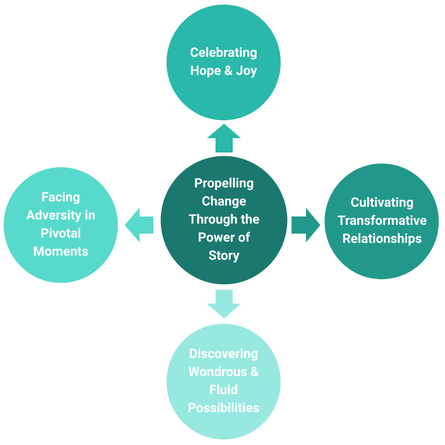

To see more classroom possibilities and helpful resources connected to Voice of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hamer, Spirit of the Civil Rights Movement, visit the Book Entry at The Biography Clearinghouse. Additionally, we’d love to hear how the interview and these ideas inspired you. Email us at [email protected] with your connections, creations, and questions. Jennifer M. Graff is an Associate Professor in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia where her scholarship focuses on diverse children’s literature and early childhood literacy practices. She is a former committee member of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8, and has served in multiple leadership roles throughout her 15+ year CLA membership. Joyce Balcos Butler is a fifth-grade teacher in Winder, Georgia, where she focuses on implementing social justice learning through content areas. She is a National Writing Project Teacher Consultant, a Red Clay Writing Fellow at the University of Georgia, and a member of CLA. BY JEANNE GILLIAM FAIN ON BEHALF OF THE NCBLA 2021 COMMITTEEThe NCBLA 2021 committee has the following charge as a committee:

The charge of the seven-member national committee is to select 30 books that best exemplify the criteria established for the Notables Award. Books considered for this annual list are works of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry written for children, grades K-8. The books selected for the list must meet the following criteria: 1. be published the year preceding the award year (i.e. books published in 2021 are considered for the 2020 list); 2. have an appealing format; 3. be of enduring quality; 4. meet generally accepted criteria of quality for the genre in which they are written; 5. meet one or more of the following criteria:

Books transport us into new places and sometimes take us out of the craziness of the world. This was one of those years where we experienced unexpected challenges. I led this committee as we navigated some of the real challenges of the pandemic. To be perfectly honest, in September when we didn’t have the normal number of books, I panicked. I am truly thankful for this thoughtful committee that continually encouraged me to keep going as I contacted publishers in hopes of obtaining more physical copies of books. Many publishers returned from turbulent times and physical copies of books were difficult to obtain. However, as a committee member, it’s just easier to dig deeper with a text when you have a physical copy in front of you. Thankfully, publishers started returning to sending physical copies of books at the end of January and in February. We continue to be so thankful for the support many publishers extended to us as they worked diligently to send our committee books. However, that meant, that we had to read on a rigorous schedule and we often had to meet more than twice a month in order to have critical conversations around the literature. Here’s a figure that highlights our process as a committee: Recurrent Themes from the 2021 NCBLA List

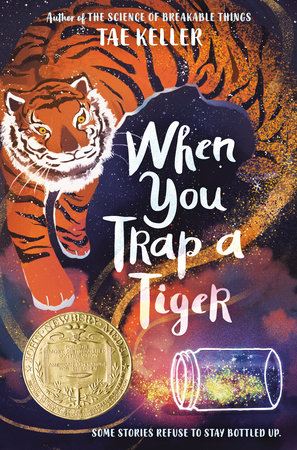

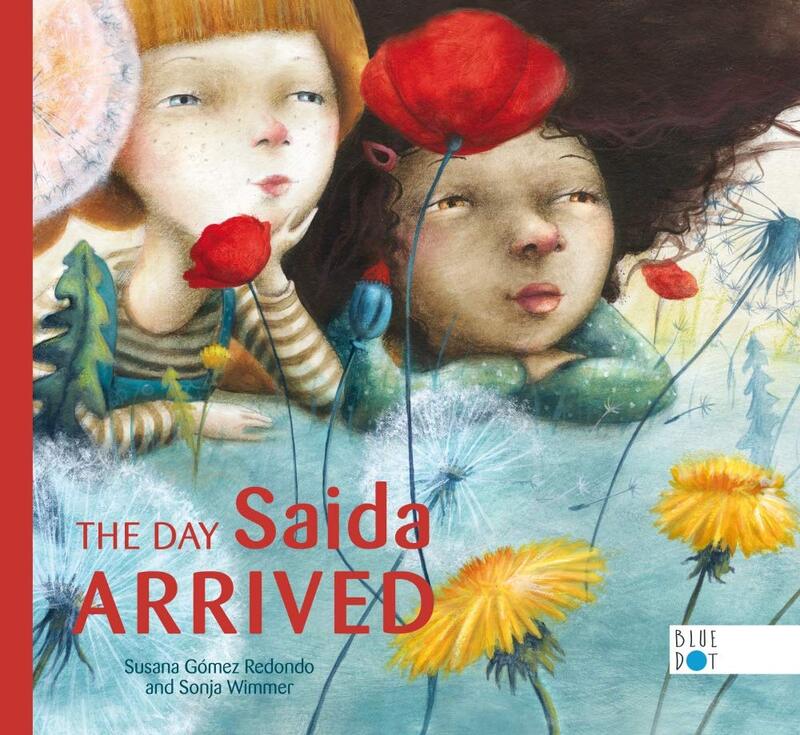

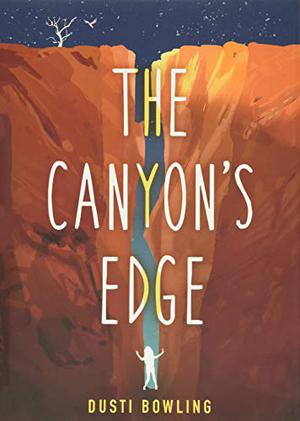

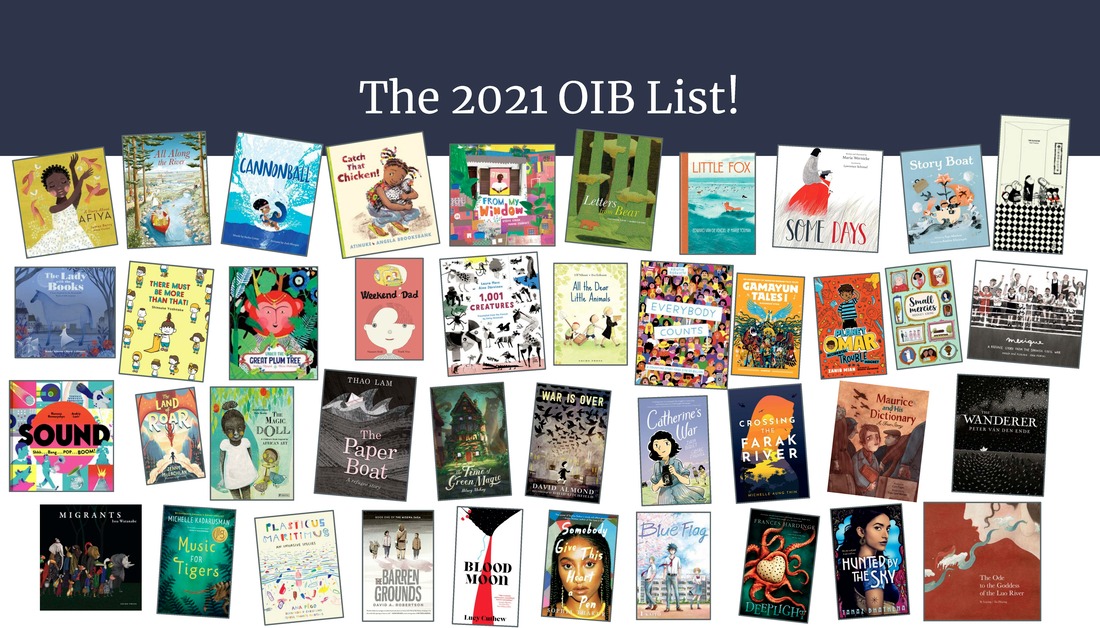

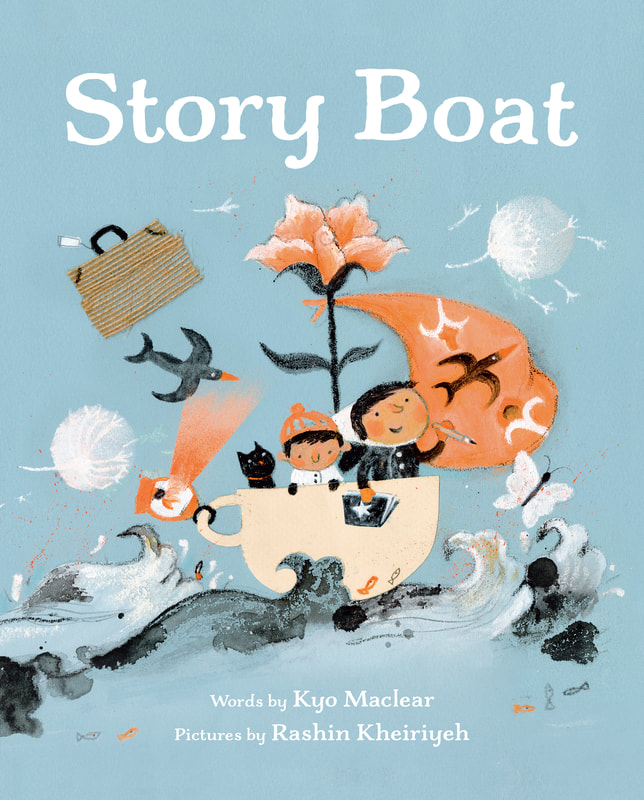

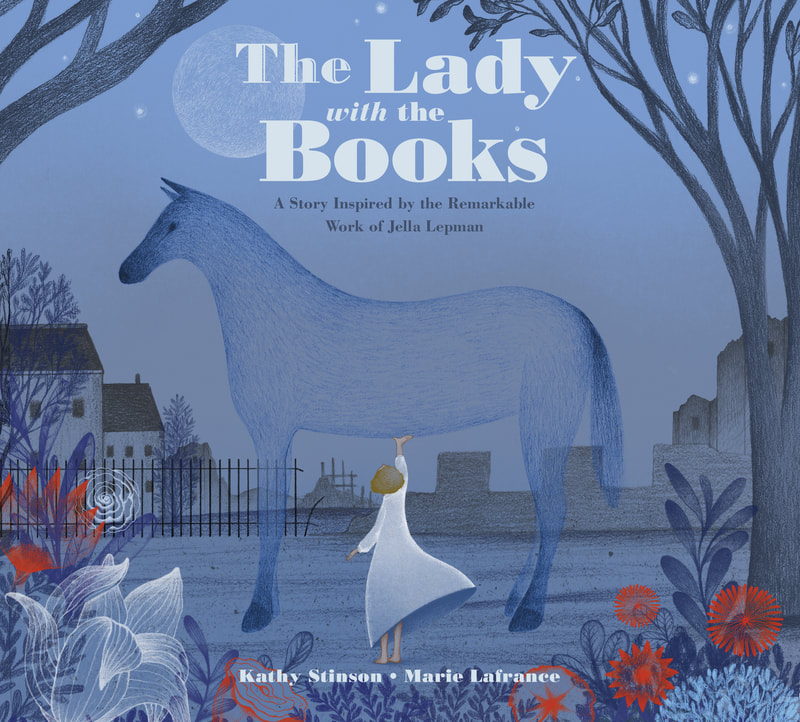

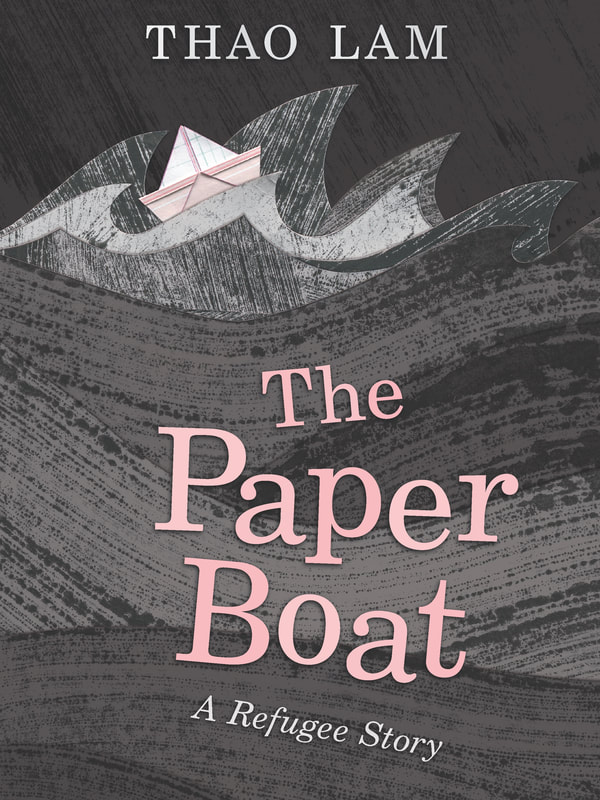

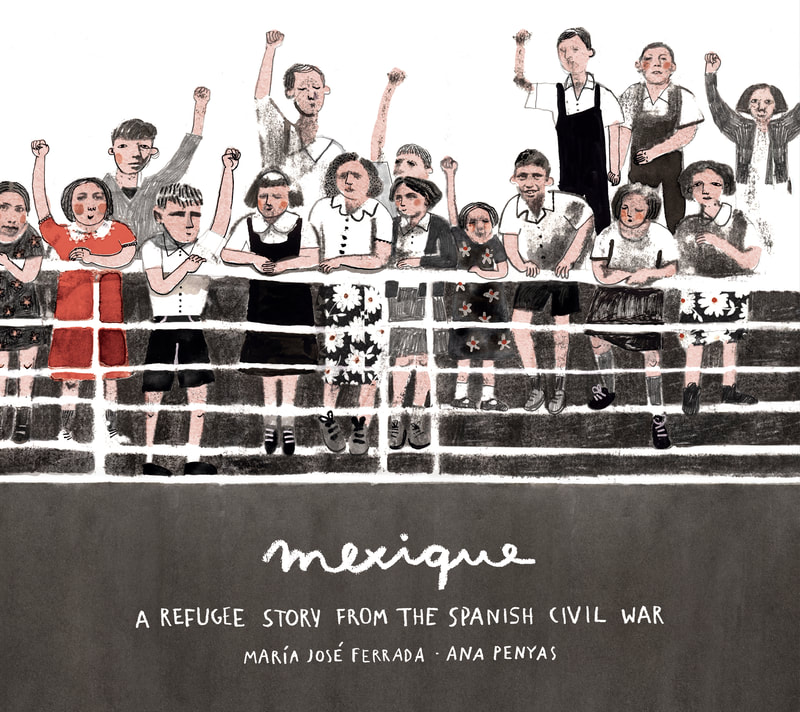

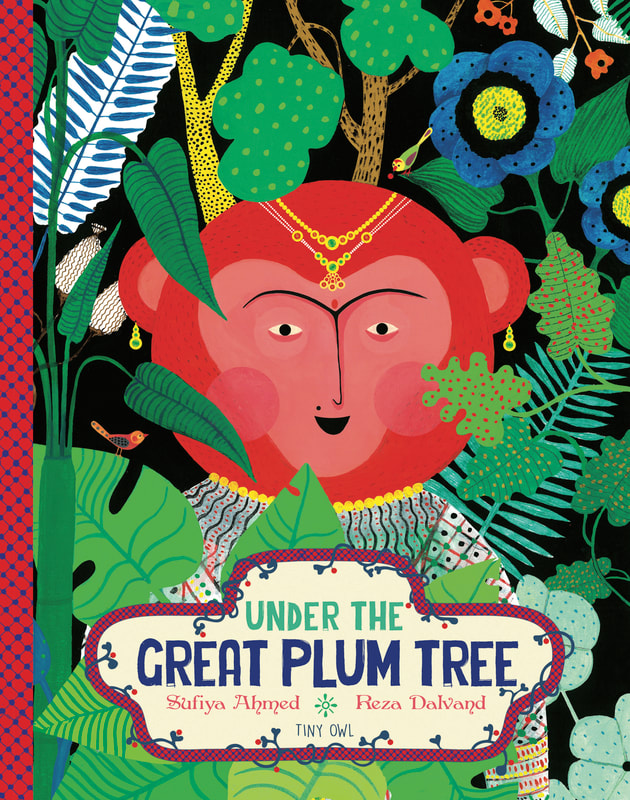

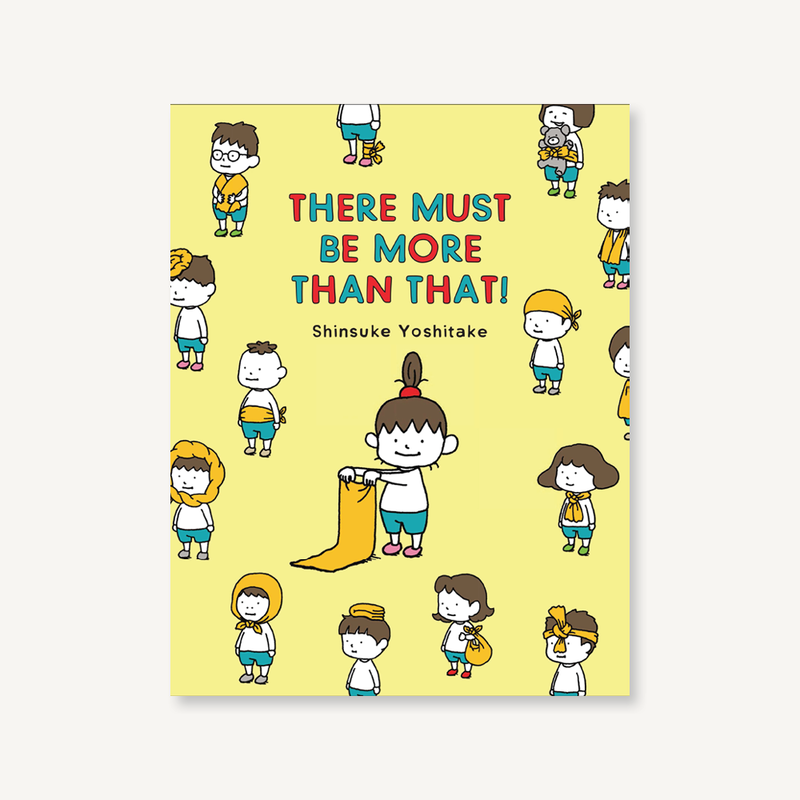

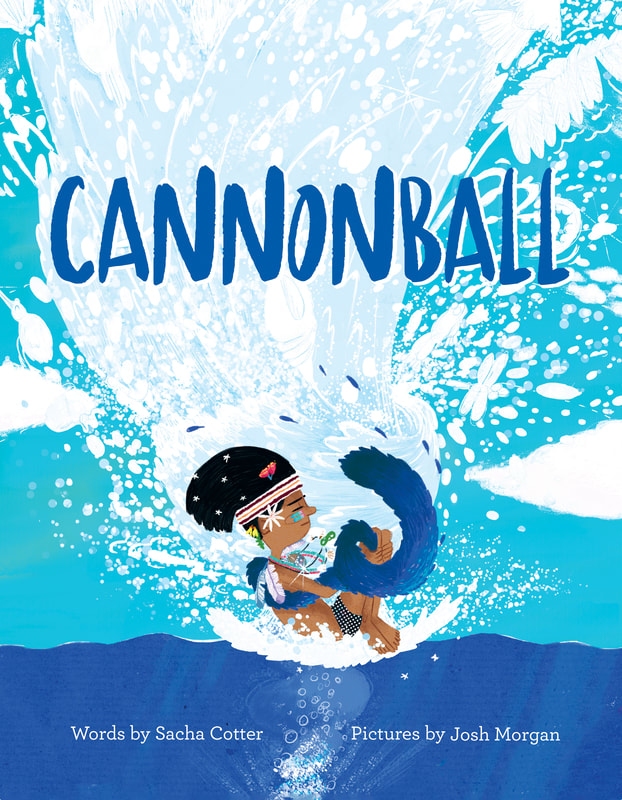

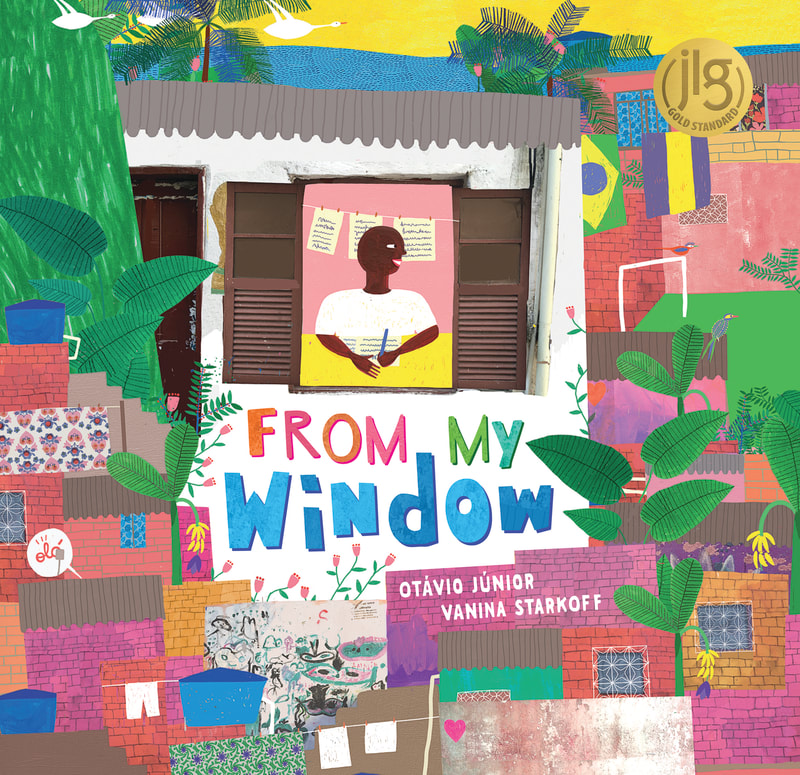

Some of the 2021 NCBLA Books We invite you to see the power of literature across our 2021 NCBLA Book List!Jeanne Gilliam Fain is s a professor at Lipscomb University in Nashville, Tennessee and Chair of the 2021 Notables Committee.

2021 Notable Children's Books in the Language Arts Selection Committee Members

An Inquiry of the Outdoors: Contemporary Children’s Picture Books that Feature the Outdoors3/25/2021

BY KATHRYN CAPRINOHow are humans and the outdoors connected? This inquiry question has been answered more acutely for some during COVID. Whereas I am grateful that I could spend time outside daily during quarantine, taking walks with my little boy and rekindling my passion for running, I know many others - for a myriad reasons - were trapped indoors. In this post, I share three contemporary children’s picture books that will help young readers answer the inquiry question: How are humans and the outdoors connected? After sharing brief summaries of each text, I provide a few lesson ideas.

Whereas COVID is not mentioned explicitly, the narrator reveals that there was a time when most people went inside. Sharing that humans made the best of their challenging months inside, the text leaves readers with hope of reconnecting with others outside - but not before emphasizing that even though we are all different on the outside, we are all the same on the inside. Echoes of the idea that humans need to be outside seen in Outside In are also seen in Outside, Inside, and this idea that we are all united by something much greater than ourselves links with Swashby and the Sea. Sharing the Books with StudentsBefore sharing these three texts with students, pose the inquiry question How are humans and the outdoors connected? Invite them to share the ways in which they feel connected to the outdoors via discussions, written responses, or pictures. Next, read the texts to students, providing opportunities for during-text discussions and post-text answering of the inquiry question. Ask students to reveal how each text confirms or alters their previous responses. After reading all three texts, ask students to draw, write, or discuss their response to the inquiry question, using their personal experiences and what they thought about as a result of the three picture books. Finally, have students engage in an activity that helps them engage with the inquiry question How are humans and the outdoors connected? in personal ways. They may want to create a project that helps keep the outdoors a hospitable place for humans. They might write to the town mayor to share some ideas on roadside trash collection, for example. Other students may pursue a more personal project, such as a drawn or written memoir or children’s picture book about their experiences with being inside and outside throughout the past year. Perhaps the best lesson idea I have, however, is to let these texts inspire you and your students to go outside. Take an awe walk to find inspiring objects and return to the classroom to discuss or write about them. Set up an observation log in your classroom so students can track what they noticed about the outdoors. Let students draw or paint the outdoors. Or even better yet, truly be outside with them - not outside but really inside as Outside In warns - and play with them. It is my hope that these three contemporary books that provide the opportunity for us to engage in an inquiry of the outdoors inspire us all to move and think and be outside just a bit more. Kathryn Caprino is a CLA member, on the Editorial Board of the Journal of Children’s Literature, a blogger at katiereviewsbooks.wordpress.com, and an Assistant Professor of PK-12 New Literacies at Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania. You can follow her on Twitter @KCapLiteracy. BY JENNIFER M. GRAFF AND BETTIE PARSONS BARGER “The stories you read can transform you. They can help you imagine beyond yourself. When you read a great story you leave home. We leave home to find home.”

(Rochman & McCampbell, 1997, p. vii) The COVID-19 Pandemic has significantly shifted global travel to “zooming” from digital screen to digital screen and surfing online streaming services. For those fatigued by such excursions, international children’s books can offer exciting and thought-provoking adventures of the heart, mind, spirit, and global consciousness. Readers can enter fantastic worlds, hear previously unheard voices and perspectives, learn more about scientific worlds and cultural communities, and become immersed in emotional episodes that speak to senses of humanity and belonging in books published on multiple continents. The United States Board on Books for Young People (USBBY)’s annual Outstanding International Books (OIB) list is a great go-to guide for such literary experiences. As mentioned in Wendy Stephens’ overview of youth literature awards and described by USBBY President, Evie Freeman, the OIB list provides readers of all ages--especially educators and readers in grades PreK-12--a collection of 40-42 books originally published outside of the United States (U.S.) that are now available in the U.S. These books, selected by a committee of teachers, librarians, children’s literature and literacy education teacher educators and scholars, connect us to noteworthy international authors and illustrators who seek to entertain, inform, challenge, delight, stimulate, and unite people through story.

Engaging with the 2021 OIB List: A Geographical Map and Themed Text Sets  Even with the grade-level band organization of the OIB list, selecting which books to read might feel daunting. Two ways to help facilitate book selections are the Interactive Google Map and thematic text sets. Each OIB list has its own interactive Google Map, illustrating the international communities represented by the selected books. Using the color-coded pins on the world map or the left sidebar, select a book to zoom in on its location. Additional uses of the maps include critical analyses and discussions about dominant/absent voices, cultural representations, and equity on a global scale. The 2021 OIB books also fit within text sets conducive to interdisciplinary and socioemotional learning as well as differentiated instruction. The table below includes the 35 OIB titles identified for PreK-8 grades organized into five themes. While each book is mentioned once, many could fit into multiple themes. The variety of genres, formats, and cultural origins reminds us that storytelling and humanity have no borders and amplifies the connections and intersections of self and society. Visit the USBBY OIB website or the February issue of the School Library Journal for all of the book annotations.

References Rochman, H., & McCampbell, D. Z. (1997). Leaving home. HarperCollins Children’s Literature References The OIB 2021 Bookmark has bibliographic information for the aforementioned books. Jennifer M. Graff is an Associate Professor in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia, is a former CLA President and has been a CLA Member for 15+ years. Bettie Parsons Barger is an Associate Professor in the Department of Curriculum and Pedagogy at Winthrop University and has been a CLA Member for 10+ years. BY WENDY STEPHENS In addition to the ALSC awards described in the previous post, the Young Adult Library Association (YALSA) also designates award-winning and honor books for adolescent literature. Among the best-known awards for adolescent literature is the Michael L. Printz Award for Excellence in Young Adult Literature, administered by YALSA. However, there are many other opportunities to learn about exceptional literature for teens. The life and legacy of Margaret A. Edwards are honored through two award designations:

A shortlist of finalists for two of YALSA's flagship awards -- the YALSA Excellence in Nonfiction for Young Adults Award, honoring the best nonfiction books for teens and the William C. Morris Award, which honors a debut book written for young adults by a previously unpublished author, are announced in December, with the winner of each being part of the press conference.

In addition to designating award books, YALSA also compiles book list resources that can aid librarians and teachers in selecting books that appeal to young adults. A decade ago, YALSA moved four of its lists onto The Hub, its literature blog platform, so that youth services librarians involved in collection development could benefit from more real-time input. All four categories post throughout the year, leading to year-end lists reflecting that year's best titles. Those include:

Outside the Monday morning announcements, there are myriad other titles to explore. Among those, the United States Board on Books for Young People (USBBY) uses Midwinter to announce its Outstanding International Books (OIB) list showcasing international children's titles -- books published or distributed in the United States that originated or were first published in a country other than the U.S. -- that are deemed the most outstanding of those published during that year. RISE: A Feminist Book Project for ages 0-18, previously the Amelia Bloomer Project, is a committee of the Feminist Task Force of the Social Responsibilities Round Table (SRRT), that produces an annual annotated book list of well-written and well-illustrated books with significant feminist content for young readers. There are even genre fiction honors. For the past four years, the Core Excellence in Children’s and Young Adult Science Fiction Notable Lists designates notable children’s and young adult science fiction, organized into three age-appropriate categories, also announced at Midwinter. Next year, we will have another treat to look forward to when the Graphic Novel and Comics Round Table (GNCRT) inaugurates its Reading List. That's a lot of books! What are the can't-miss titles? I train my students to look for overlaps, like Candace Fleming winning this year for information text across age ranges. What does it indicate when the Sibert and YALSA's Nonfiction Award overlap? When a book is honored by both the Printz and YALSA Nonfiction? Though the in-person announcement is exhilarating, especially the view from the seats at the front of the auditorium reserved for committee members, the webcast approximates its energy and allows you to share with students in real-time. To make sure you catch all of the lists, follow the press releases from ALA News and on twitter. Until next January! Wendy Stephens is an Assistant Professor and the Library Media Program Chair at Jacksonville State University. BY WENDY STEPHENSEditorial Note: This post is the first in a 2-part series by Wendy Stephens discussing the rich landscape of book awards announced over the winter months. In this first post, Wendy focuses on ALSC awards and awards by ALA affiliates recognizing books for children or books for a wide spectrum of age groups. The second post, which will be published next week, will present awards for YA literature administered by YALSA, as well as several other notable awards. When we talk about budgeting for materials, I always advise my school librarian candidates to be sure to save some funding for January. No matter how good their ongoing collection development has been throughout the year, there are always some surprises when the American Library Association's Youth Media Awards (YMAs) roll around, and they'll want to be able to share the latest and best in children's literature with their readers. These are the books that will keep their collections up-to-date and relevant. From our own childhoods, we always remember the "books with the medals" -- particularly the John Newbery for the most outstanding contribution to children's literature and the Randolph Caldecott for the most distinguished American picture book for children. These books become must-buys and remain touchstones for young readers. In 2021, Newbery is celebrating its one hundredth year. Some past winners and honor books are very much a product of their time, and many of those once held in high esteem lack appeal today. For those of us working with children and with children's literature, the new books honored at Midwinter offer opportunities to revisit curriculum, update mentor texts, and build Lesesneian "reading ladders." Each award committee has its own particular award criteria and guidelines for eligibility, and its own process and confidentiality norms. Every year, the YMAs seems to be peppered with small surprises. Does New Kid winning the Newbery means graphic novels are finally canonical? Is Neil Gaiman an American? What about all the 2015 Caldecott honors, including the controversial That One Summer? Did the Newbery designation of The Last Stop on Market Street mean you can validate using picture books with older students? How does Cozbi A. Cabrera's much-honored art work resonate at this historical moment? In Horn Book and School Library Journal, Newbery, Caldecott and Printz contenders are tracked throughout the year in blogs like Someday My Printz Will Come, Heavy Medal, and Calling Caldecott. Other independent sites like Guessing Geisel, founded by Amy Seto Forrester are equally devoted to award prediction. Among librarians and readers, there are lots of armchair quarterbacks, and conducting mock Newbery and Caldecotts, either among groups of professionals or with children, have become almost a cottage industry. There are numerous how-tos on that subject, from reputable sources like The Nerdy Book Club and BookPage. But there are numerous other awards announced at ALA Midwinter almost simultaneously that deserve your attention, too. Among the Association for Library Services for Children (ALSC) awards are: the Robert F. Sibert Medal, the Mildred L. Batchelder Award, the Geisel Award, the Excellence in Early Learning Digital Media Award, and the Children's Literature Legacy Award.

Aside from the award winners, each year annual ALSC Children's Notable Lists are produced in categories for Notable Children's Recordings, Notable Children's Digital Media, and Notable Children's Books. If you want to see the machinations behind the designation, those discussions are open to the public this year via virtual meeting links. Outside of ALSC, many of ALA’s affiliates have their own honors for children's literature. These include the Ethnic and Multicultural Information Exchange Round Table (EMIERT) which sponsors the Coretta Scott King Book Awards; the Association of Jewish Libraries which sponsors the Sydney Taylor Book Awards; and REFORMA: The National Association to Promote Library and Information Services to Latinos and the Spanish-Speaking which sponsors the Pura Belpré awards. In addition to these affiliates, others such as the Asian/Pacific American Librarian Association and the American Indian Library Association also present awards. The awards are always evolving to reflect the abundance of literature available for young people. Like the Association of Jewish Libraries and the Asian/Pacific American Librarian Association awards, the American Indian Youth Literature Awards were first added to the televised YMA event in 2018. And this year was the first year for inclusion for a new Young Adult category for the Pura Belpré. Two awards of particular significance are the Stonewall Book Award – Mike Morgan and Larry Romans Children’s and Young Adult Literature Awards are given annually to English-language works found to be of exceptional merit for children or teens relating to the gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender experience, and the Schneider Family Book Awards, honoring authors or illustrators for the artistic expression of the disability experience for child and adolescent audiences, with recipients in three categories: younger children, middle grades, and teens.

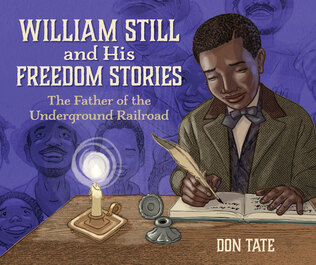

Wendy Stephens is an Assistant Professor and the Library Media Program Chair at Jacksonville State University. BY AMINA CHAUDHRI AND MARY ANN CAPPIELLO, ON BEHALF OF THE BIOGRAPHY CLEARINGHOUSE “William Still’s records, and the stories he preserved, reunited families torn apart by slavery. Because that’s what stories can do. Protest injustice. Sooth. Teach. Inspire. Connect. Stories save lives.” - Don Tate, from William Still and His Freedom Stories: The Father of the Underground Railroad  As 2021 begins, we want to acknowledge the continued need to show young people that Black Lives Matter. Part of that responsibility is shifting our curriculum away from a white-centered view of U.S. history and towards a more multifaceted exploration of all of the communities that have lived on this land from prehistory to today. Don Tate’s picturebook biography William Still and His Freedom Stories: The Father of the Underground Railroad, this month’s featured text on The Biography Clearinghouse, is an important text to help make this change in elementary and middle school classrooms. William Still and his Freedom Stories is one of several recent publications that highlights the role of African Americans in the freedom struggle, countering the narrative that freedom from slavery depended on the actions of whites. A precise, linear narrative takes readers through significant events that shaped William Still’s understanding of the world and his role in making it better for African Americans. Readers follow Still from childhood to adulthood, bearing witness to his desire to learn, the grueling labor he endured to earn a living, and eventually, the risks he took to secure freedom for enslaved people and his post-Civil War activism to fight segregation. This deeply-researched and powerfully-illustrated book has layers of curricular potential: as a read aloud, as a mentor text for literacy skill development, as a model of the genre of biography, as an important piece of history, and much more. Operating within the Investigate, Explore, and Create Model of the Biography Clearinghouse, we designed teaching ideas geared toward literacy and content area learning as well as opportunities for socio-emotional learning and strengthening community connections using William Still and His Freedom Stories. Featured here are two teaching ideas inspired by William Still and His Freedom Stories. The first engages students deeply with the text itself - its form and content, and the second extends learning beyond this picturebook to explore multiple sources for inquiry and research.

Advocating for and Learning from 19th Century Black-Authored Texts For far too long, too many students in the U.S. have been taught a white-centered modern history that avoids a close examination of imperialism and the legacy of Europe’s colonial reach. The brutal history of the global slave trade of the 17th - 19th centuries has been marginalized as have the many stories of Black agency, resistance, and liberation. As a consequence, young people - and many adults - have limited knowledge of that history. We need this to change. William Still and His Freedom Stories is one text that helps to make that change. In this teaching idea for middle school students, we leverage the conversations that this book can open with more in-depth research writings of 19th century activists such as William Still and 19th century Black journalists.

Amina Chaudhri is an Associate Professor of Teacher Education at Northeastern Illinois University. She is a reviewer for Booklist and a regular contributor to Book Links. Mary Ann Cappiello teaches courses in children’s literature and literacy methods at Lesley University, blogs about teaching with children’s literature at The Classroom Bookshelf, a School Library Journal blog, and is a former chair of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8. By: William Bintz & Meghan ValerioPicture books are for everybody at any age, not books to be left behind as we grow older. (Anthony Browne, 2019)

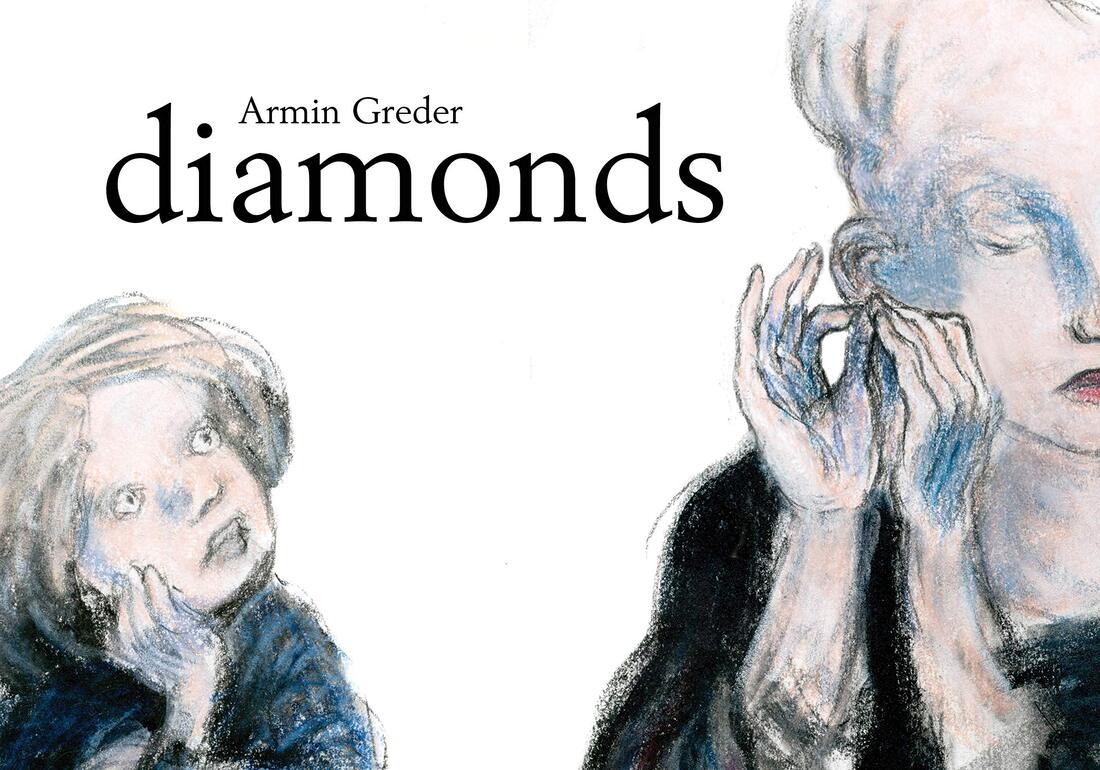

This intriguing diamond industry story depicts the controversial journey of diamonds from source to customer, including the appalling conditions, black market, and blind ignorance of customers rich enough to purchase them. It is a disturbing and evocative depiction of how the diamond industry, historically and contemporaneously, feeds an insatiable appetite for diamonds, and in the process, also perpetuates inequality, conflict, and corruption. Metaphorically, this visually unsettling book removes the sparkle from diamonds. Diamonds (Greder, 2020) is not a novel, short story, nor poem. It is a picturebook, with approximately 32 pages, minimal text (195 words), and single and double-spread illustrations. It is not, however, a traditional picturebook – it is a crossover picturebook (see Table 1 for more examples).

Benefits of Crossover PicturebooksCrossover picturebooks invite teachers to shift perspectives and think differently about the nature of childhood and the purpose of curriculum. In terms of childhood, crossover picturebooks posit that teachers Never Read Down, Always Read Up to children. Reading down sees the child as innocent and in need of protection; reading up sees the child as capable of understanding sophisticated topics (Dressang & Kotrla, 2009). Reading down suggests that limiting or eliminating access to controversial issues protects the innocence of children; reading up conceives the danger of withholding information from youth as exceeding the danger of providing it (Dressang, 1999). Curriculum utilizing crossover picturebooks is rooted in an inquiry-based model. This model builds on curiosity and supports inquiry for teachers and students. Within this model, instruction based on crossover picturebooks:

A Concluding, But Not Final, ThoughtPicturebooks are synonymous with children’s literature. But is this a necessary condition of the art form itself? Or is it just a cultural convention, more to do with existing expectations, marketing prejudices and literary discourse? There is no reason why a 32-page illustrated story can’t have equal appeal for teenagers or adults as they do for children (Tan, 2003, np). We end with a concluding, not a final, thought, because we hope this post will start new conversations, not close them down. This thought is eloquently expressed by internationally renowned author and illustrator, Shaun Tan. Yes, picturebooks have been, and continue to be, synonymous with children’s literature. Is it time to shift perspective and think differently about this kind of literature? If so, we believe crossover picturebooks are a good conversation starter for readers of all ages. References

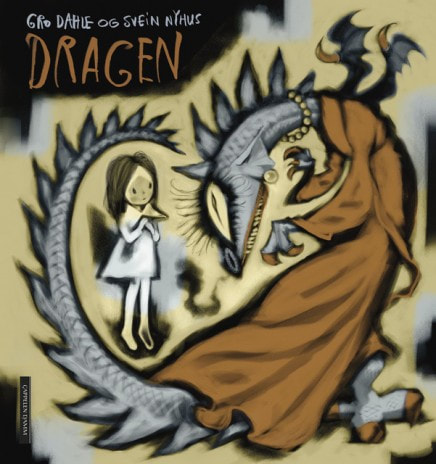

Meghan Valerio is a doctoral student in Curriculum and Instruction with a Literacy emphasis at Kent State University. Meghan’s research interests include investigating literacy and cognitive development from a critical literacy perspective, centering curricula to understand reading as a transactional process, and exploring pre- and in-service teacher perspectives in order to enhance literacy instructional practices and experiences. William Bintz is Professor of Literacy Education in the School of Teaching, Learning, and Curriculum Studies at Kent State University. His professional interests include the picturebook as object of study, literature across the curriculum K-12, and collaborative qualitative literacy research. BY MEGHAN VALERIO & WILLIAM BINTZRecently, I (William) introduced crossover picturebooks in a graduate literacy course to students pursuing a reading specialization Master’s degree. All students were practicing teachers ranging from elementary through high school. Each week, I read aloud a crossover picturebook to introduce the class session. Selected picturebooks dealt with themes including death and dying, divorce, suicide, mental illness, physical disability, parent-child separation, and other life-changing and impactful events. One example is Dragon by Gro Dahle (2018). It tells the story of Lilli, a young girl who is a child abuse victim by her mother. Lilli regards her mother as a dragon because she is explosive, hot-tempered, and abusive. After reading, I invited students to share their questions and reactions to crossover picturebooks. Three questions and one reaction were particularly illustrative:

These responses inspired this blog post. They revealed teachers may not know much about crossover literature but are curious to know more about it. What are Crossover Picturebooks?Crossover literature, or texts written for dual-aged audiences, is not a new genre, as many books could be considered crossover already. While picturebooks specifically might be enjoyed by both children and adults, crossover picturebooks, a subset of crossover literature, are written and illustrated intentionally for both children and adults, breaking conventional assumptions that books are intended for one age group (Falconer, 2008; Harju, 2009, Rosen, 1997). Crossover authors communicate purposeful messages to both audiences equally (Harju, 2009). Narratives then are considered ageless and timeless, often portraying issues that might be deemed controversial including death, verbal and physical abuse, and divorce. In a world where in-person and online book shopping and borrowing is organized by genre and age, this makes these “ageless” books complex. Consider first an adult purchasing a picturebook for themselves, and on the flip side, encouraging a child to purchase a book about abuse. Both instances could be questionable, even alarming to some. While there are truly designated texts for children, like aesthetic and sensory appealing babybooks (Kümmerling-Meibauer, 2015), crossover picturebooks defy traditional book categorizing norms, causing anyone interested to rethink what counts as children’s literature vs. adult. Children’s literature though is written and published by adults for children (Rosen, 1997). So really, is there such a thing as a true children’s book if the text isn’t written by children at all? What Concerns Does This Raise?Currently, we are conducting research on crossover picturebooks. Specifically, we are exploring teacher concerns on using this literature in the classroom. Based on this research, two major findings indicate that many K-12 teachers worry about the following issues:

These concerns, and many others like them, are real for teachers. Traditionally, children’s literature is to be enjoyable not uncomfortable, entertaining not controversial. Crossover literature invites a different perspective and pushes the envelope on censorship and what constitutes taboo topics in classrooms. To help explore this further, we recommend the following resources. These resources include picturebooks and professional literature that have pushed our thinking about crossover literature. We hope they will push yours.

ReferencesBishop, R.S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6 (3). Falconer, R. (2008). The Crossover Novel: Contemporary Children’s Fiction and Its Adult Readership. London, UK: Routledge. Harju, M.L. (2009). Tove Jansson and the crossover continuum. The Lion and the Unicorn, 33(3), 362-375. Kümmerling-Meibauer, B. (2015). From baby books to picturebooks for adults: European picturebooks to the new millennium. Word & Image, 31 (3), 249-264. Rosen, J. (1997). Breaking the age barrier. Publishers Weekly. 243 (6). Meghan Valerio is a doctoral student in Curriculum and Instruction with a Literacy emphasis at Kent State University. Meghan’s research interests include investigating literacy and cognitive development from a critical literacy perspective, centering curricula to understand reading as a transactional process, and exploring pre- and in-service teacher perspectives in order to enhance literacy instructional practices and experiences. William Bintz is Professor of Literacy Education in the School of Teaching, Learning, and Curriculum Studies at Kent State University. His professional interests include the picturebook as object of study, literature across the curriculum K-12, and collaborative qualitative literacy research. |

Authors:

|

CLA

About CLA

|

Journal of Children's Literature

Write for JCL

|

ResourcesCLA-sponsored NCTE Position Statements

|

Members-Only Content

CLA Video Library

|

© COPYRIGHT 2018.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed