By Xenia Hadjioannou, Lauren Aimonette Liang & Liz Thackeray Nelson As yet another unusual school year is drawing to a close, we remain grateful for all the teachers who worked through novel challenges, who never lost sight of their students as humans with curiosities and the desire to learn, and who continued to share all kinds of books with them. Books that spoke to who individual students are and affirmed and bolstered their identities, books that allowed them to glimpse ways and experiences different than their own, and books that fed their wonderings and offered well-researched information about the world. Books they would have picked up anyway but got to experience and think about with others through their classroom communities, and books they would have never read if it weren't for a teacher or a librarian setting them in their hands. As you are shifting to your summer rhythms, we hope that you will be afforded time for rest and rejuvenation and that you will find plenty of fascinating new reads for both your personal and professional reading stacks.

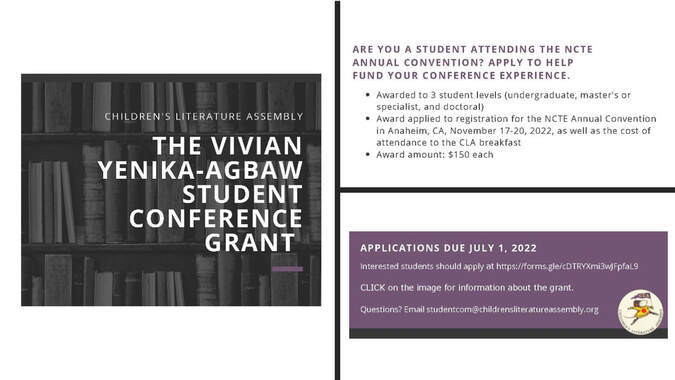

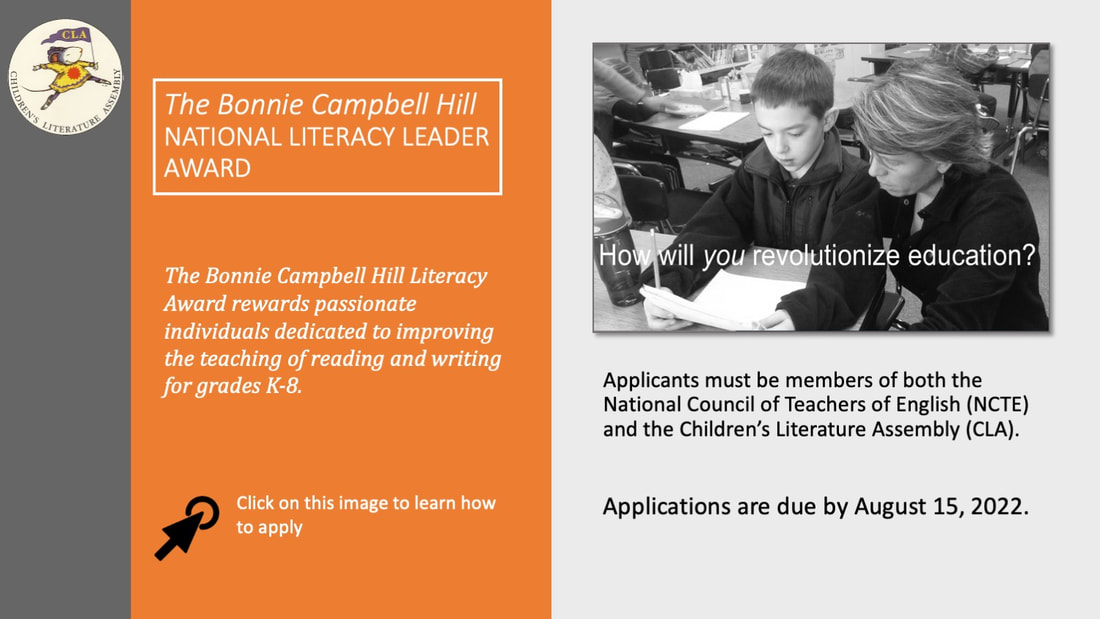

If you are a CLA member, we also encourage you to consider applying for one of the CLA grants and awards to support your professional activities for the coming academic year.

Information about the three awards and how to apply can be accessed below. Happy Summer to all and we look forward to "seeing" you in the fall when the CLA Blog returns! Warmly, Xenia, Lauren and Liz Co-editors of the CLA Blog 2022 CLA Grants and Awards

By Denise Dávila on Behalf of the Biography Clearinghouse

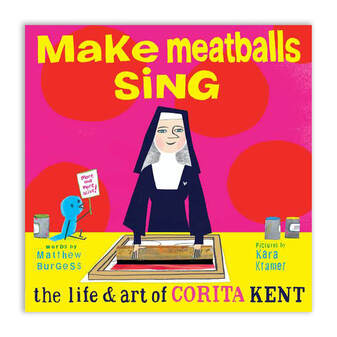

Using Viewfinders Sister Corita Kent authored provocative multimodal compositions that were inspired by looking closely at ordinary objects and were imbued with intertextual meanings. As suggested in Make Meatballs Sing, much of her work began by focusing her attention on specific elements and blocking out others. She employed cardboard viewfinders with her students as tools for developing the skill of looking. These next activities build upon the use of viewfinders in the classroom. They are adapted from the Make Meatballs Sing Curriculum Guide.

Denise Dávila is an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin. She studies children’s literature and researches the home literacy practices of families with young children in under-resourced communities. By Angela Wiseman and Ally Hauptman, Breakfast Committee co-chairs

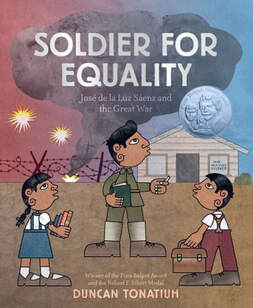

Ally Hauptman is a CLA Board Member and co-chair of the 2022 CLA Breakfast Committee. She is an associate professor at Lipscomb University in Nashville, TN. Angela Wiseman is a CLA Board Member and is co-chair of the 2022 CLA Breakfast Committee. She is an associate professor of literacy education at North Carolina State University. By Erika Thulin Dawes and Xenia Hadjioannou on behalf of the Biography Clearinghouse  We close out the school year immersed in social strife and conflict. Our students are grappling both with big questions about humanity and substantial uncertainties about everyday life. Recent research describes rising mental health concerns for young people (Acheson, 2020; Cowie & Myers, 2021; Samji et al. 2022) and it’s not surprising that maintaining optimism is challenging in the context of war, a global pandemic, and climate change. As educators, we are seeking ways to provide our students with grounding and with hope. And we believe that biographies, life stories of inspiring people, can help to provide both an anchor and inspiration. Our latest Biography Clearinghouse entry features Duncan Tonatiuh’s picturebook biography Soldier for Equality: José de la Luz Sáenz and the Great War. Using his trademark illustrative style, digital collage inspired by Mixtec Pre-Columbian art, Tonatiuh describes the World War I experiences of ‘Luz’; a teacher, activist, Texan, and a person with Mexican heritage. Toniatiuh’s biography of José de la Luz Sáenz is a powerful narrative of the transformative power of literacy. Luz’s education and multilingualism were instrumental in his life trajectory; his knowledge allowed him to navigate the battlefield safely, keeping him out of the trenches and instead in a fortified command post for the intelligence service. He developed his skills in organizing while teaching English to Mexican American soldiers. And upon his return to teaching when the war was over, he turned his outrage over unequal schooling for Mexican American children into activism, establishing the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), an organization that helped to end the segregation of Latinx children from white schools. In our Biography Clearinghouse entry, we provide an interview with Duncan Tonatiuh and a collection of teaching ideas to support student exploration of Soldier for Equality. These teaching ideas encourage students to consider the transformative power of literacy and the generative power of community organizing and activism. They include: an exploration of translanguaging and theme development in picturebooks; a history of and contemporary look at the experience of minoritized populations in the United States army; a call to allyship to counter bullying; a visual literacy exercise exploring traditional artistic motifs; and a tribute to teacher activists. Below is an excerpt of the teaching ideas in the Biography Clearinghouse entry for Soldier for Equality: José de la Luz Sáenz and the Great War:

Teachers as Activists

Citations Acheson, R. (2020). Research digest: The impact of the covid-19 pandemic on child, adolescent, young adult, and family mental health. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 46(3), 429-440. https://doi.org/10.1080/0075417X.2021.1912810 Cowie, H., & Myers, C. (2021). The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the mental health and well‐being of children and young people. Children & Society, 35(1), 62-74. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12430 Samji, H., Wu, J., Ladak, A., Vossen, C., Stewart, E., Dove, N., Long, D., & Snell, G. (2022). Review: Mental health impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic on children and youth – a systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 27(2), 173-189. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12501 Erika Thulin Dawes is a Professor of Language and Literacy at Lesley University where she teaches courses in children’s literature and early childhood literacy and is the program director of the graduate Early Childhood Education program. Erika is a former chair of NCTE’s Charlotte Huck Award for Outstanding Fiction for Children. Xenia Hadjioannou is an Associate Professor of Language and Literacy Education at the Harrisburg campus of Penn State University where she teaches and works with pre- and in-service teachers through various courses in language and literacy methodology. She is the Vice President and Website Manager of the Children's Literature Assembly, and a co-editor of The CLA Blog. The Bonnie Campbell Hill National Literacy Leader Award

|

|

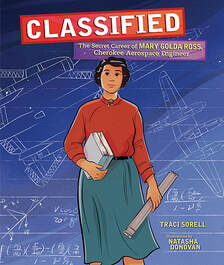

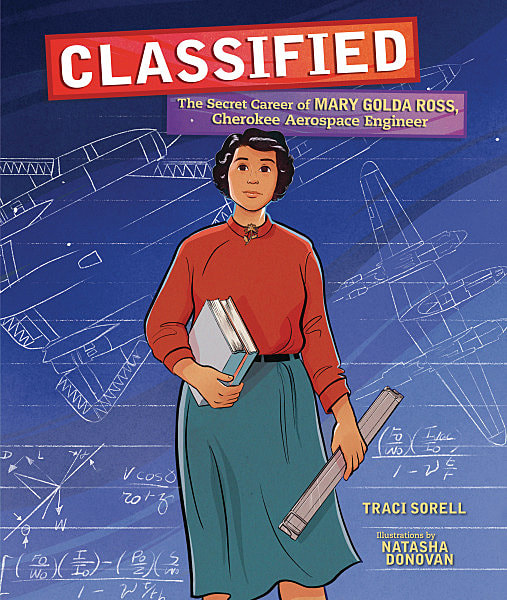

Classified: The Secret Career of Mary Gold Ross, Cherokee Aerospace Engineer by Cherokee author Traci Sorell and Métis illustrator Natasha Donovan is an excellent example of a biography that features a woman in a STEM career. The book shows Mary’s love of mathematics and traces her path from teaching, to becoming Lockheed’s first female engineer, and then a member of the Skunk Works division working on satellites and spacecraft.

Extensive back matter includes a timeline, photos, an author’s note, an explanation of the Cherokee values mentioned in the text, source notes, and a bibliography. Illustrations showcase some of the aircraft Mary worked on such as the Lockheed A-12 and the Starfighter F-104C, as well as equations related to the projects. |

- Read the Smithsonian article “Mary Golda Ross: Aerospace Engineer, Educator, and Advocate.”

- Read the Smithsonian article “Mary Golda Ross: She Reached for the Stars.”

- Watch the Reading Rockets video: “Traci Sorell: Classified: Mary Golda Ross, Cherokee Aerospace Engineer.”

- Access the author’s website for additional materials that explore the Cherokee values Mary personified.

- There is also a Classified Teaching Guide which contains many activity ideas for experimenting with the forces of flight.

|

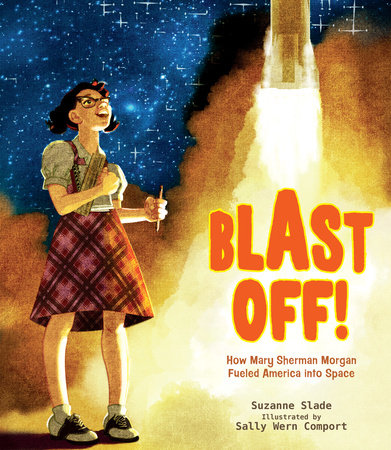

Blast Off! How Mary Sherman Morgan Fueled America into Space written by Suzanne Slade and illustrated by Sally Wern Comport is another of the untold stories of the space program. Working with two engineers as her assistants, Mary Sherman Morgan created the rocket fuel hydyne which powered the launch of the first American satellite into space. This biography explores Mary’s late start in school, her determination to pursue a career in chemistry, and her work at North American Aviation.

This book also has plenty of back matter with photos, a timeline, a selected bibliography, and more details about Mary, the Juno 1 rocket and the Explorer 1 satellite. The author’s note includes an explanation of how difficult it was to find information. She states, “Mary Morgan’s history is not well-documented. Unfortunately, that is true of many women who have made meaningful contributions to science and other fields.” Thanks to the author’s persistence in reaching out to family members, people from Mary’s hometown, and aerospace experts, she was able to create this inspiring story. |

- The book trailer shows the important launch Mary was working toward with her rocket fuel.

- This NASA video tells more about Explorer 1 and its lasting legacy for space exploration.

- NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory has a web page on Explorer 1 with links to photos, videos, and other information.

- In this short BBC video George Morgan talks about his mother and Rocket Girl, the book he wrote about her work developing rocket fuel.

- To make experiments of their own about the perfect fuel ratio for a rocket launch, students might enjoy working with fizzy rockets and trying out different proportions of water to Alka-Seltzer tablets to power the launch. SciTech Labs has posted a how-to video.

- There is also a lesson plan with instructions available from the Civil Air Patrol.

By Mary Ann Cappiello, Jennifer M. Graff and Melissa Quimby on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse

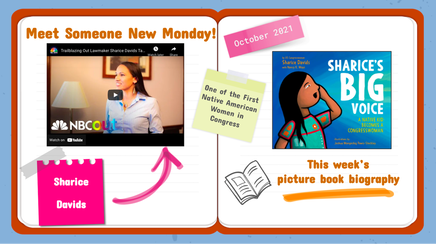

Melissa Quimby, a 4th grade teacher in Massachusetts, has written the inaugural entry in our new feature “Stories from the Classroom.” Melissa is the genius behind #MeetSomeoneNewMonday, a weekly initiative that has spread from her classroom to her grade level team to an entirely different school in just three years.

This initiative launched when Melissa decided to share her passion for picturebook biographies with her students through interactive read-alouds. They were hooked! As Melissa writes, “Over time, I molded this project in intentional ways, and it evolved into an adventure that focused on identity, centered marginalized and minoritized communities, and cultivated thoughtful, strategic middle grade readers.” What started as a way to share nonfiction picturebooks as an engaging and compelling art form developed into a more nuanced exploration of global changemakers–past and present. With their weekly reading of picturebook biographies, students grow as readers and thinkers and deepen their individual and collective sense of agency.

In the following excerpts, Melissa describes how she reveals each week’s notable changemaker to her students and shares some of her picturebook biography selections.

Monday Read-Aloud Routines

Reveal Slide Example

Reveal Slide Example Some weeks, interactive read aloud time happens on Monday morning immediately following the reveal. On some Mondays, it works best for us to huddle up in the afternoon. Occasionally, we steal pockets of time throughout our busy schedule to enjoy the biography of the week in smaller doses. When we read the text is not as important as how we read the text. The heart of this work truly lies in how we generate emotional investment within our students and how we help our students’ reactions and ideas blossom into new thinking about the world and ways that they can take action in their own lives for themselves and others. Sometimes, we simply read the biography to love it. In those moments, readers are silent with their eyes glued to the book, scanning the illustrations, wide-eyed when something surprising happens. Perhaps they whisper something to their neighbor, let out an audible gasp or share a comment aloud. Sometimes, we read to grow ideas. In these moments, readers are tracking trouble, considering how the figure responds to obstacles. They are ready to turn to their partner and reach for a precise trait word or theme and supporting evidence.

You can also reach out to Melissa through her website (QUIMBYnotRamona) or Twitter (@QUIMBYnotRamona) to discuss how to implement #MeetSomeoneNew initiative in your classroom or school.

Inspired by Melissa’s picturebook biography initiative or done something similar? Share your ideas and stories with us via email: thebiographyclearinghouse@gmail.com. Or, chime in on Twitter (@teachwithbios), Facebook, or Instagram with your own #teachwithbios ideas and picturebook biography recommendations.

Mary Ann Cappiello teaches courses in children’s literature and literacy methods at Lesley University, blogs about teaching with children’s literature at The Classroom Bookshelf. She is a former chair of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8.

Jennifer M. Graff is an Associate Professor in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of Georgia where her scholarship focuses on diverse children’s literature and early childhood literacy practices. She is a former committee member of NCTE’s Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction K-8, and has served in multiple leadership roles throughout her 16+ year CLA membership.

By Tiffeni Fontno

Reintroduced into the conversation through The Crown Act, even in education, Black hair has been policed through discriminatory school codes and policy standards, widening the marginalization against culturally inclusive, responsive, and sustainable identity practices.

Black hair has been subjected to colorism, discrimination based on color, and texturism; the belief that certain hair textures are better than others. Based on enslavement and Western standards of beauty, the idea of "good hair," straight more European, and "bad hair," hair that is curlier and kinkier, creates a standard of sociocultural standards that are a source of contention to this very day (Byrd, 2001).

Culturally responsive teaching involves incorporating culture, knowledge, language, perspectives, and experiences into the curriculum and instruction for more engaging and meaningful learning experiences (Ladson-Billings, 2009). Educators may not be culturally proficient or prepared through teacher education programs to connect with the nuances of relationship building and teaching diverse student populations (Gay, 2002). In this post, I share books and resources for educators to learn and understand the importance of the representation and appreciation of Black hair for students from kindergarten through-8th grade.

History

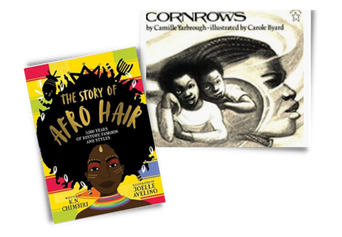

Centered from a Black British perspective, Chimbiri’s non-fiction book The Story of Afro Hair sensitively tells a detailed account of the history of Black hair. This stylized journey details hairdos, products, innovations, the science of Black hair, and the philosophy behind styles, like locks.

Also included in the back matter are a glossary and additional references.

Cornrows (Elementary-Middle School)

Cornrows is a fictional story that intertwines and connects the history and pride of Black culture through hair design. Released in 1997, Yarbrough's book, told through the storytelling of Great-Grammaw, inspires pride, hope, and courage.

Both books provide an entryway to a discussion on Black hairstyles, through cultural understanding and historical significance.

Hair Care

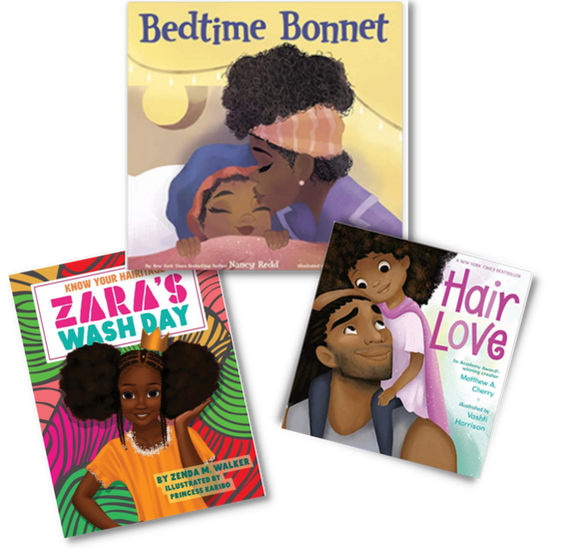

| Bedtime Bonnet (Elementary) Nancy Redd’s Bedtime Bonnet shows the Black experience of the nighttime hair routine, which many people of African descent experience. The illustrator Nneka Myers does a beautiful job showing the different textures of hair and preparation. Know your Hairitage: Zara’s Wash Day (Elementary-Middle School) Know your Hairitage: Zara’s Wash Day by Zenda Walker and illustrated by Princess Karibo tells the story of Zara, who is frustrated by the weekly ritual of wash day and not having silky straight hair. While doing Zara’s hair, her Mom explains the cultural significance and connection of different styles to regions of Africa and the Rastafari influence, which gives Zara a greater appreciation of her identity. The back matter has a glossary of hairstyles, geographical and cultural terms. Hair Love (Elementary) Hair Love by Matthew Cherry follows a father who bravely takes on the challenge of doing his daughter Zuri’s hair for the first time. Using online video tutorials this story shows, dad navigating products and accessories to try and create the perfect hairdo to make Zuri happy. |

International Books

| The following books provide insight into Black hair stories and perspectives beyond America to understand the prevalence of Black hair stigma and culture internationally. Bad Hair Does Not Exist!/Pelo Malo No Existe! (Elementary-Middle School) Author Sulma Arzu-Brown's bilingual book uses different phrases to describe kinky, curly hair to counter the negativity of the term ‘pelo malo’ while instilling pride and self-worth. This book is framed through the Afro-Latinx perspective and identity. Arzu-Brown words are culturally affirming throughout the story by reiterating that bad hair doesn’t exist. Bintou’s Braids (Elementary-Middle School) Bintou’s Braids by Sylvaine A. Diouf, is the Senegalese story of a young girl who impatiently wants the longer, more complex, braided hairstyles of the women in her village. We learn about the culture of maturation from girlhood to womanhood in understanding self-acceptance and identity through this story. Bintou learns the lesson of patience and enjoying being a child instead of receiving things immediately. |

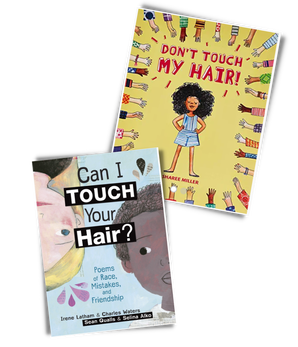

Don't TouchDon’t Touch My Hair (Elementary-Middle School) Don’t Touch My Hair by Sharee Miller addresses the importance of agency and boundaries. This book gives a funny take on a serious topic of cultural curiosity, permission, and understanding differences. Can I touch Your Hair? (Elementary) Told in paired poems, Qualls and Alko’s Can I touch Your Hair? Poems of Race, Mistakes, and Friendship, explores race through navigating childhood friendships. The story centers on Irene and Charles, who are classmates working together on a 5th-grade poetry project. They struggle, awkwardly negotiating challenging moments to relate to one another while working on completing their school project. |

Boys and Barbershops

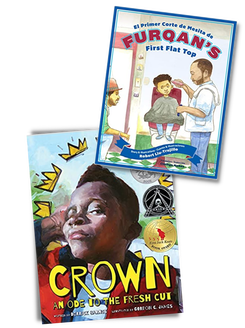

| Barbershops are a significant space in the Black community, especially for Black males. The following books provide perspectives on the barbershop experience. El Primer Corte Mestiza de Fuquan/Furqan's First Flat Top (Elementary) Robert Liu-Trujillo’s bilingual story of Furqan who wants a cool new haircut as he anxiously visits the barbershop for the first time. Crown: Ode to the Fresh Cut (Elementary-Middle School) The story, Crown: Ode to the Fresh Cut, authored by Derrick Barnes and illustrated by Gordon James, pays tribute to the barbershop as a community space by experiencing the ‘glow-up’ and joy of getting the perfect cut that gives the feeling that anything is possible. |

Educator PreparationIn addition to resources in the blog, I’ve created a K-12 guide that lists trade books about the culture of Black hair, providing background knowledge for educators. Books, journal articles, news stories about policing Black hair, and The Crown Act legislation are included. The resources accumulated provide context to creating discussion and ways of knowing in relating and relaying Black culture to validate, teach and normalize cultural differences of hair in affirm student identities.

|

Boston College Libraries

|

References

Dabiri. (2020). Twisted : the tangled history of black hair culture (First U.S. edition.). Harper Perennial.

Gay, G. (2002). Preparing for Culturally Responsive Teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(2), 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487102053002003

Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African American children (2nd ed..). Jossey-Bass Publishers.

|

Tiffeni Fontno is Head Librarian at the Educational Resource Center of Boston College Libraries. She is a former classroom teacher and school librarian.

|

Social Media:

Instagram: @bcerclibrary Twitter: @ResourceBc |

By Jessica Whitelaw

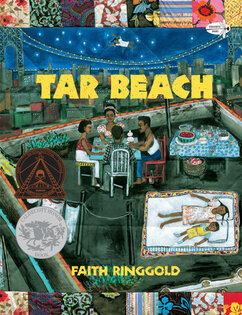

| Woman on a Bridge #1 of 5: Tar Beach, 1988 Acrylic paint, canvas, printed fabric, ink, and thread Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Gift, Mr. and Mrs. Gus and Judith Leiber, 1988 | But from an educator perspective, this important exhibit left out something important about the arts, access, and critical literacy. It didn’t pay much attention to the radical act of making this story quilt, and all of the ideas that it explores, available to young people in the form of another everyday object, the picturebook. In the book version of Tar Beach, narrator Cassie Louise Lightfoot, “only eight years old and in the third grade,” invites readers into an experience and conversation that the story quilt was asking museum audiences to consider. Cassie’s is a story of resistance and self-definition and an invitation through art and words, to encounter issues of class, race, place, history, and the future through what Ringgold has called a “fantastical sensibility.” Cassie’s story offers a word/picture narrative marked by sharp observation and critique but also beauty and humanization. |

| I left the exhibit thinking about how Tar Beach provides an object lesson in how the arts can support critical literacy. With its imprint on the social and cultural imagination of so many, Tar Beach reminds us that we can look to the humble picturebook to find sources of radical power. In these everyday objects that can traverse home, school, and everyday life, we can seek out art and words to explore issues of cultural significance, often with an eye toward joy and justice at the same time. So how can we harness the power and possibility of the arts that can be found in picturebooks? How can we invite and encourage deep critical literacy and inquiry? |

Adapted from the steps of art criticism, this protocol provides a framework for sharing picturebooks that aims to cultivate a critical practice. It guides the reader through a process of looking closely to notice what they might otherwise overlook and to use what they know about words and pictures to analyze and make sense of what they see. The stages offer a helpful way to support students of any age through a process and unfolding of critical engagement that relies upon attention to specific details in the work to guide thoughtful engagement and response. The protocol is intended as a facilitation guide for teachers. Wording should be adjusted for the audience/age of the reader.

Take inventory. Examine the cover of the book, the dust jacket and the endpapers. Look closely at the typography, the pictures, the words. Describe what you see and notice in detailed, descriptive language.

Use what you know about picturebooks and design to analyze the words and the pictures. Look at the colors, the lines, shapes, textures. Try to determine the media the artist used to make the pictures. Examine the style of the language the writer used. Look for patterns, repetition, rhyme. Draw attention to the picturebook as a unique form of the book that relies on the synergy of the words and the pictures by asking how the words and pictures work together: What do the words tell you that the pictures do not? What do the pictures tell you that the words do not? What happens in between the openings?

Use questions together to probe and deepen. Stop and ask questions about pages that are visually and/or verbally rich or complex. What sense do you make of this page? How do you know that? Why do you think the author or illustrator chose to do it the way they did? What questions does the page raise for you, make you wonder about?

What do you think the author/illustrator is trying to do or say or show in this book? Who do we see in this book? Who is the audience for this book? Who do you think should read it? Whose voice/voices do we hear? Who do we not hear from? What ideas do you have about the topic/topics in the book? What do you think the storyteller in this book believes or thinks or wants us to know? What questions do you have about what the storyteller is saying and showing? What genre/category does the book belong to? What other work has this author and/or illustrator created and how is it similar to or different from this book?

After having looked closely at the book, what does this text mean to you? What does the story make you wonder about? How could this story mean different things? To you? To different readers?

Watch Faith Ringgold read Tar Beach

Create a paper story quilt

Listen to Faith Ringgold’s favorite songs

Explore a Faith Ringgold Text Set:

- We Came to America

- Cassie’s Word Quilt

- The Invisible Princess

- Aunt Harriet’s Underground Railroad in the Sky

- Harlem Renaissance Party

- If a Bus Could Talk: The Story of Rosa Parks

- Henry Ossawa Tanner: His Boyhood Dreams Come True

For Older Readers: Watch the Ted Talk by Kimberlé Crenshaw on intersectionality

Examine how Tar Beach explores identity and power at several intersections. Examine other artworks of Faith Ringgold such as her For the Women’s House mural at the Brooklyn Museum or her America series of paintings on the artist’s website

Read Ringgold’s feminist artist’s statement from her memoir, We Flew Over the Bridge. Look for themes that connect across and examine how the different art forms allow the themes to be explored differently. Read other excerpts from We Flew Over the Bridge: The Memoirs of Faith Ringgold, and examine how ideas from her life take shape in Tar Beach. Consider the different forms of visual and verbal storytelling that she employs in her work and how ideas are conveyed through different modalities in each.

by Kate Narita, introduction by Melissa Stewart

The letter was also published on more than 20 blogs that serve the children's literature community--including this one—and amplified on social media as part of the #KidsLoveNonfiction campaign. (To date, more than 2,100 people have signed it.)

A few weeks later, The New York Times responded, saying it had no current plans to add nonfiction lists at this time. Many people were disappointed by this decision, including fourth-grade teacher and CLA member Kate Narita, who has written the following essay, bravely sharing how the petition changed her thinking.

-- Melissa Strewart

Shattering My Implicit Bias Against Nonfiction by Kate Narita

| My biggest aha moments in life have happened when I’ve become aware of an implicit bias that a few months earlier I would have told you I didn’t have. At the end of last year, I would have told you with 100 percent certainty that I embrace and support nonfiction readers as much as fiction readers. I would have told you about knowing that 42 percent of young readers prefer expository nonfiction and another 33 percent enjoy expository and narrative text equally. I would have told you that I’ve celebrated professional books like Nonfiction Writers Dig Deep and 5 Kinds of Nonfiction on my podcast. And I would have told you about the thousands of dollars I’ve spent building my nonfiction classroom book collection. All that’s true, and yet, I also would have told you my husband and younger son weren’t readers. I hadn’t seen my younger son, who’s now a 19-year old college student, read anything other than school assignments, since sixth grade. Before he entered middle school, I had some success finding fiction series he liked, such as Warriors by Erin Hunter and The Land of Stories by Chris Colfer, but after he became a smartphone owner in seventh grade, he was only interested in the screen. It never occurred to me that maybe he was reading articles there as well as playing video games and using social media. When my husband, a physics professor, picked up a novel like Harry Potter, he’d read a few pages in the beginning, a few in the middle, and a few at the end, and say he was done. “That’s not reading,” I’d say. When my sons and I discussed Harry Potter, my husband would say, “I don’t remember that part.” I would reply, “That’s because you didn’t read it.” |

“Yes,” he said. “And I really enjoyed it.”

Did his statement about enjoying a book wake me up to my implicit bias? No. But I did feel a shift inside me. I was pleasantly surprised and excited because I love talking about books. If he had read something and was excited about it, I could read it and discuss it with him, even if he had only read it because it was a class assignment. Here was a way I could deepen my relationship with him as an adult. Even if it was just a one-time occurrence.

I asked if I could read the book when he was done, and he brought it home the next time he visited.

Fast forward to February break. As my husband and I were packing for a trip to Maui to celebrate our 25th wedding anniversary, he spotted Infinite Powers in the pile of books I was sorting through on our ottoman and picked it up.

“What’s this?” he asked. When I explained, he asked if he could take it to Hawaii, and I nodded. I hadn’t read it yet because, to be honest, reading a whole book about calculus felt too daunting. Instead, I packed and read three books from Kate Messner’s History Smashers series and Rukhsanna Guidroz’s Samira Surfs.

I also spotted a copy of Kristin Hannah’s Fly Away in our condo. Since I had watched Hannah’s Firefly Lane on Netflix and was listening to The Four Winds on Libby, I couldn’t resist picking up Fly Away, and I devoured it in a day.

As my husband and I sat side-by-side reading on the beach, we talked about Infinite Powers. He told me that while he was enjoying the book, the author gave way too much credit to calculus and not nearly enough to physics.

He was kind of cranky about it. Actually, he was truly irritated. I was surprised that he was having an emotional response to the book, a nonfiction book. It had stirred up passion inside him, even though it wasn’t a novel.

Did his passion wake me up to my implicit bias? Not yet. But I did feel another shift. He was expressing emotion about a book, and I was listening. In the past, it had almost always been me expressing emotion about a novel and him listening.

When we got back home, I spotted this petition (which you can still sign) on Twitter. Two professors of literacy, Mary Ann Cappiello and Xenia Hadjioannou, had written a letter asking The New York Times to add three children’s nonfiction bestseller lists—one for picture books, one for middle grade, and one for young adults. I signed it because, of course, I fully supported nonfiction writers and readers!

A couple of weeks later, I saw on Facebook that, even though more than 2,000 people had signed the petition, The New York Times had refused to add children’s nonfiction bestseller lists. After a full day of teaching, I was tired, and reading this unfortunate news made me angry. I looked up from my phone.

Across the room, my younger son, who was home on spring break, was reading The Elegant Universe: Superstrings, Hidden Dimensions, and the Quest for the Ultimate Theory by Brian Greene for fun because he had liked Infinite Powers so much and wanted to keep reading and learning. Next to him, my husband was reading an article about the Green Bay Packers on the internet.

My husband and younger son are readers. They have always been readers.

I just didn’t realize it because narratives and fiction aren’t their jam. But give them nonfiction on topics they find fascinating—math, physics, sports—and they’re all in. They’re curious people who read to learn. They want to know about the world, how it works, and their place in it.

The decisionmakers at The New York Times seem to have their own implicit bias against children’s nonfiction, and as long as they do not include lists highlighting these books, they’re failing to acknowledge the 42 percent of our youth who crave true texts. They’re also failing to open the eyes of adults who raise those kids, thinking they’re not readers.

Maybe we should petition The Wall Street Journal next.

|

Kate Narita teaches fourth grade at The Center School in Stow, Massachusetts. She’s also the author of 100 Bugs! A Counting Book and hosts the podcast Chalk + Ink: The Podcast for Teachers Who Write and Writers Who Teach. When she’s not teaching, writing, or podcasting you can catch Kate and her handsome hound, Buck, running or hiking on Mount Wachusett.

|

By Amina Chaudhri and Courtney Shimek on behalf of The Biography Clearinghouse

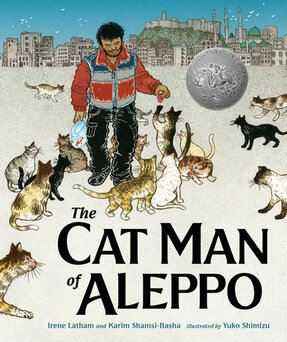

Brought to life by Yuko Shimizu’s stunning, intricate illustrations, the city of Aleppo is almost as much a character as the people in The Cat Man. In this month’s Biography Clearinghouse entry, we feature an interview with the book’s creators: Irene Latham, Karim Shamsi-Basha, and Yuko Shimizu. We also explore teaching and learning possibilities that invite readers to learn about the process of research in writing and art, about the effects of war across time and place, and about ways to analyze the illustrations and use them as mentors for new creative projects.

Below is an excerpt of the teaching ideas in the Biography Clearinghouse entry for The Cat Man of Aleppo.

Researching Visuals

Begin engaging in this work with students by discussing different elements of visual literacy. As a class, read the first half of Molly Bang’s Picture This: How Pictures Work. Given the visual nature of this book, sharing it using a document camera or leaving it available for students to explore after you read it with them is paramount. Discuss how color, shape, line, scale, texture, motion, etc. change your perception as a reader of visual images. Focus on sections such as the ones on pages 17-19 that depict Little Red Ridinghood as a small red triangle, and how the placement of that triangle on the page shapes how we perceive her vulnerability in the woods. Then select spreads in The Cat Man of Aleppo that similarly make use of composition to evoke our emotions. Some examples include the two-page spread of Alaa and the children surrounded by cats, the spread that follows immediately in which Alaa is surrounded by social media symbols, and the front and back matter spread that depicts a blue sky and white doves.

If you have 1-2 hours…. |

If you have 1-2 days…. |

If you have 1-2 weeks…. |

Compare the illustrations of The Cat Man of Aleppo to some of the other biographies we have featured on the Clearinghouse website. Notice together how the visual images in the biographies make you feel. Discuss together or in small groups: What colors, style, shape, and lines do the artists use to elicit these feelings? Focus on details included in the illustrations that give you a sense of place. How do the people look similar to or different from people in your community? What kinds of natural elements are included? What do these illustrations lead you to understand about the setting of the biography? Record these noticings on chart paper for the class to refer back to. Encourage students to continue to explore the visuals of the books they are reading independently. |

Based on the units of study going on in your classroom, select a few places around the world for students to research. Provide books, magazine articles, social media accounts, images from the internet, and even video clips for students of this place. Have students work in small groups to document what they notice about the people, the natural elements, the buildings, what roads and cars look like, etc. Based on their noticings, have students create either a digital or a paper vision board of the place they have researched. These can be shared on social media afterward or displayed on the wall for others to see. Have students notice the differences between the places they researched. |

Using the skills developed thus far and the vision boards created previously, have students work individually or as a group to create a research-informed illustration of their assigned place. Encourage students to talk about their drawings to the class or even record a TikTok video about the research they conducted, how this is evident in their illustration, and why they made the decisions they did as an artist. |

Courtney Shimek is a former Preschool teacher and an assistant professor at West Virginia University in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction/Literacy Studies. Her research interests include young readers’ approaches to nonfiction picturebooks, the convergence between literacy and play, and teacher education.

Authors:

CLA Members

Supporting PreK-12 and university teachers as they share children’s literature with their students in all classroom contexts.

The opinions and ideas posted in the individual entries are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of CLA or the Blog Editors.

Blog Editors

contribute to the blog

If you are a current CLA member and you would like to contribute a post to the CLA Blog, please read the Instructions to Authors and email co-editor Liz Thackeray Nelson with your idea.

Archives

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

October 2023

September 2023

August 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

Categories

All

Activism

Advocacy

African American Literature

Agency

All Grades

American Indian

Antiracism

Art

Asian American

Authors

Award Books

Awards

Back To School

Barbara Kiefer

Biography

Black Culture

Black Freedom Movement

Bonnie Campbell Hill Award

Book Bans

Book Challenges

Book Discussion Guides

Censorship

Chapter Books

Children's Literature

Civil Rights Movement

CLA Auction

CLA Breakfast

CLA Expert Class

Classroom Ideas

Collaboration

Comprehension Strategies

Contemporary Realistic Fiction

COVID

Creativity

Creativity Sponsors

Critical Literacy

Crossover Literature

Cultural Relevance

Culture

Current Events

Digital Literacy

Disciplinary Literacy

Distance Learning

Diverse Books

Diversity

Early Chapter Books

Emergent Bilinguals

Endowment

Family Literacy

First Week Books

First Week Of School

Garden

Global Children’s And Adolescent Literature

Global Children’s And Adolescent Literature

Global Literature

Graduate

Graduate School

Graphic Novel

High School

Historical Fiction

Holocaust

Identity

Illustrators

Indigenous

Indigenous Stories

Innovators

Intercultural Understanding

Intermediate Grades

International Children's Literature

Journal Of Children's Literature

Language Arts

Language Learners

LCBTQ+ Books

Librarians

Literacy Leadership

#MeToo Movement

Middle Grade Literature

Middle Grades

Middle School

Mindfulness

Multiliteracies

Museum

Native Americans

Nature

NCBLA List

NCTE

NCTE 2023

Neurodiversity

Nonfiction Books

Notables

Nurturing Lifelong Readers

Outside

#OwnVoices

Picturebooks

Picture Books

Poetic Picturebooks

Poetry

Preschool

Primary Grades

Primary Sources

Professional Resources

Reading Engagement

Research

Science

Science Fiction

Self-selected Texts

Small Publishers And Imprints

Social Justice

Social Media

Social Studies

Sports Books

STEAM

STEM

Storytelling

Summer Camps

Summer Programs

Teacher

Teaching Reading

Teaching Resources

Teaching Writing

Text Sets

The Arts

Tradition

Translanguaging

Trauma

Tribute

Ukraine

Undergraduate

Using Technology

Verse Novels

Virtual Library

Vivian Yenika-Agbaw Student Conference Grant

Vocabulary

War

#WeNeedDiverseBooks

YA Lit

Young Adult Literature

RSS Feed

RSS Feed